Published 10 December 2020

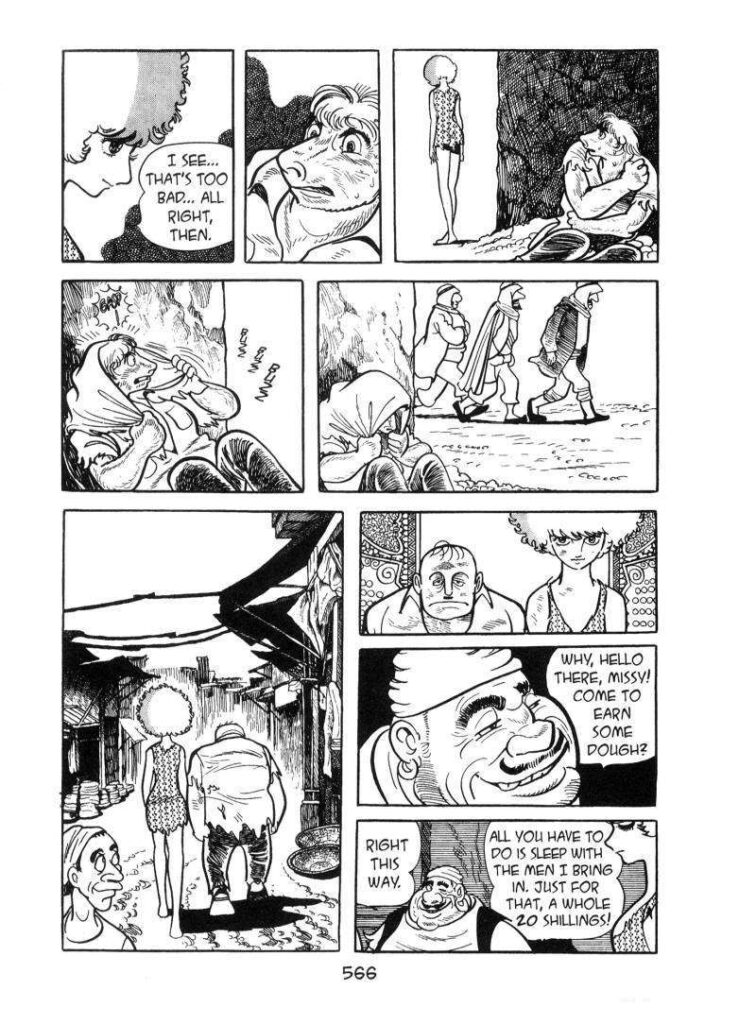

Content warning for sexual violence. Also, every sort of violence. Quite lurid. If you are a minor, get out of here! Stop reading this page!

Tezuka Osamu (1928–1989) is like Mark Twain, not in that his writing is like Mark Twain’s, but in that he is a writer whom I like even though, if asked, I could not point to any story of his I can honestly say I like. The venerable Tezuka-sensei is like Mark Twain in one way, at least: he needs no introduction. His influence is immense. For his rejection of a safer medical career in favor of his artistic passion, his obsessive dedication to productivity, and his perhaps unparalleled output of cartoons, he is a personal hero of mine. The rejected medical career might be salient, given the subject of this post.

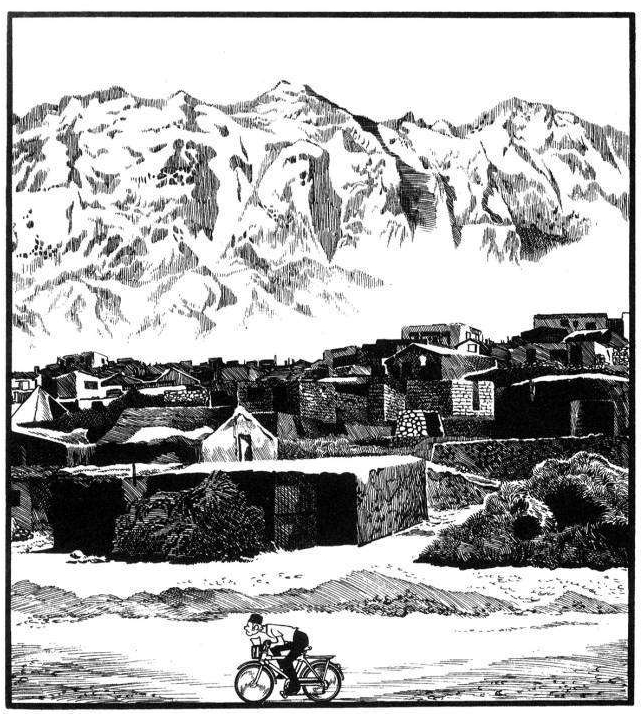

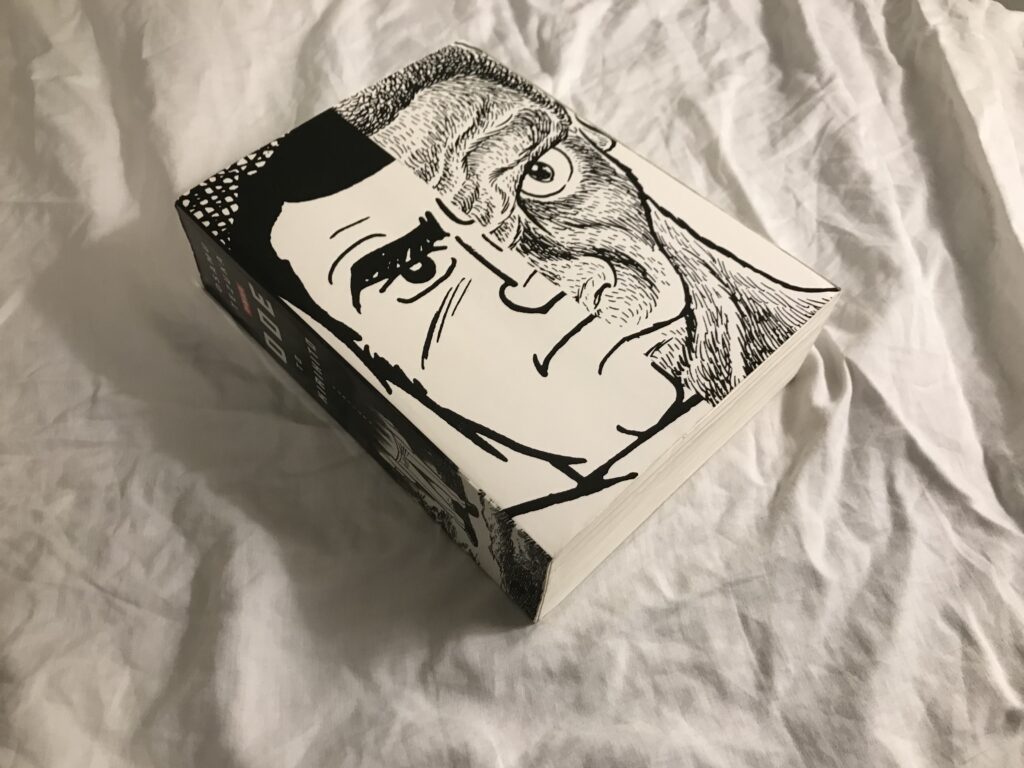

Ode to Kirihito happens to be the most recent of Tezuka’s books I have read, of course in English translation. It is not an especially famous or representative work (and is awful). In this case, I read the 2006 printing from Vertical, translated by Camellia Nieh. Credit your translators, people! They’re essential! The later English printings divide the book into two volumes, a sensible enough decision, given that this nearly one-thousand-page first edition can be a bit ungainly to hold. Evidently, Ode to Kirihito, though a paperback, included a dust jacket that concealed half the cover, allowing the reader to slide it back and forth to see Kirihito before or after his transformation. A stylish touch. The only other novelty dust covers that come to mind are those of David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp and Brian Lee O’Malley’s Seconds. Though I am half-certain that the image used for the transformed Kirihito is not actually Kirihito!

The Vertical printing suffers from a particular misstep. Japanese comics, being written, of course, in Japanese, read right to left. These days, the standard practice for the “Western” translations is to simply ask the audience to adjust to reading panels from right to left. Unfortunately, Vertical opted to mirror the artwork so that the book can be read left to right! Why? Did the editors expect that the nerds and Japanophiles who would seek out some obscure, grizzly Tezuka manga aren’t willing to read right to left? This poor decision doesn’t ruin Tezuka’s artwork, per se, but does leave the whole book feeling a little off, and the characters’ suits buttoned and kimono folded on the wrong side. At least the editors appear to have bothered preserving the correct orientation in panels that feature text as part of the scenery, rather than in the speech balloons. Still, distorting the illustrations is a mistake. Words might demand translation, but images are universal. I hated it in Vertical’s printing of Message to Adolf, and I hate it here!

But enough about the physical book. What of the story in those pages? Ode to Kirihito, completed in 1971, falls into Tezuka’s early dark period, when he drifted away from the family-friendly fare that made him famous and into the gekiga style that had become popular among many mangaka. For those unfamiliar, Wikipedia defines gekiga thus: “It describes comics aimed at adult audiences with a cinematic style and more mature themes.” I would add, from the gekiga I have read, that these more mature themes tend to include sex, nudity, rape, suicide, gruesome violence, surrealism, nihilism, and (a lot of the time) literary ambitions.

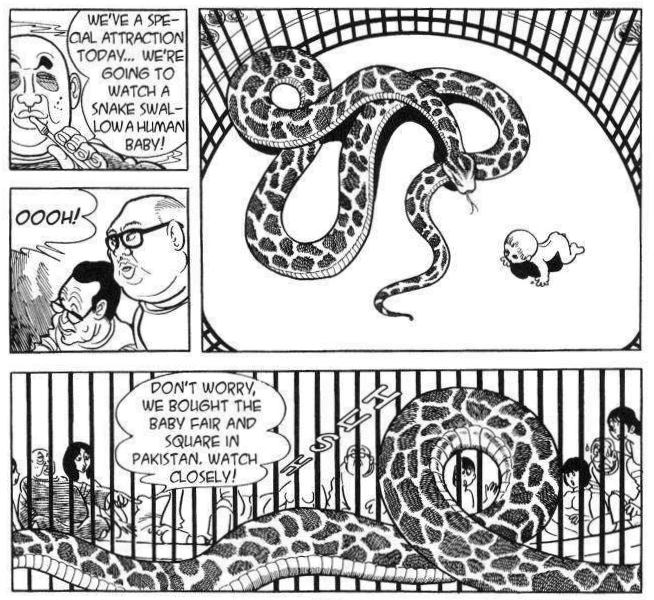

A brief explanation of what brought me to Kirihito will suffice to show that these bleak descriptors apply to to today’s subject. Back in March, at the very beginning of the pandemic, I had a thirst for something horrific, something that would make my skin crawl like The Drifting Classroom, and remembered seeing comic panels online somewhere that depicted men watching a snake swallow a human baby. I thought this scene came from a Tezuka manga and traced the panels to Ode to Kirihito. Some, or at least Andrew D. Arnold on the back cover, consider Kirihito a horror manga. Arnold also writes: “Brutal, depraved and savage, Kirihito will leave you panting like a beaten dog-man.”

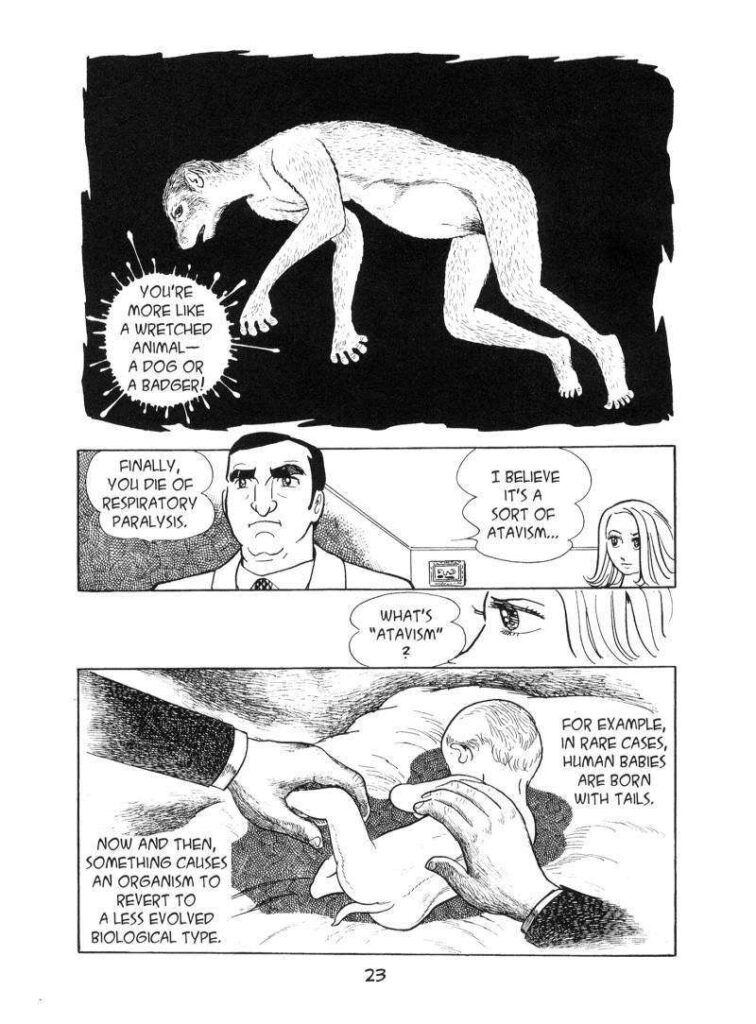

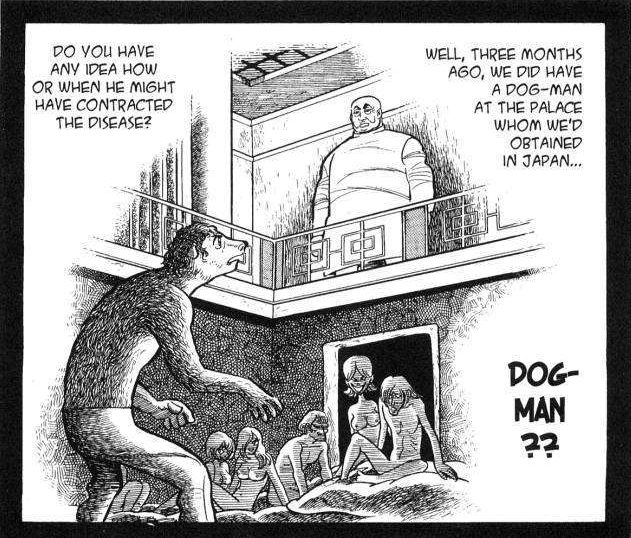

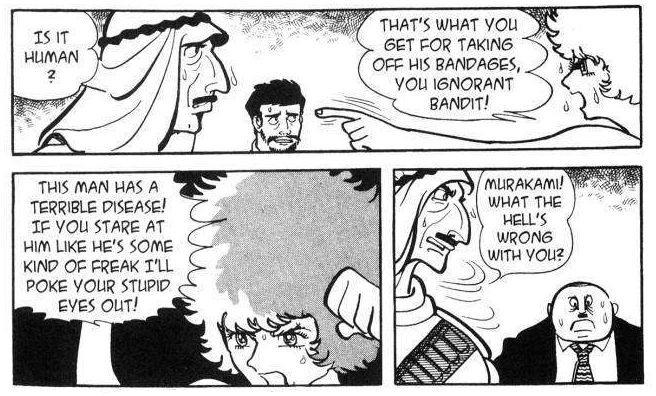

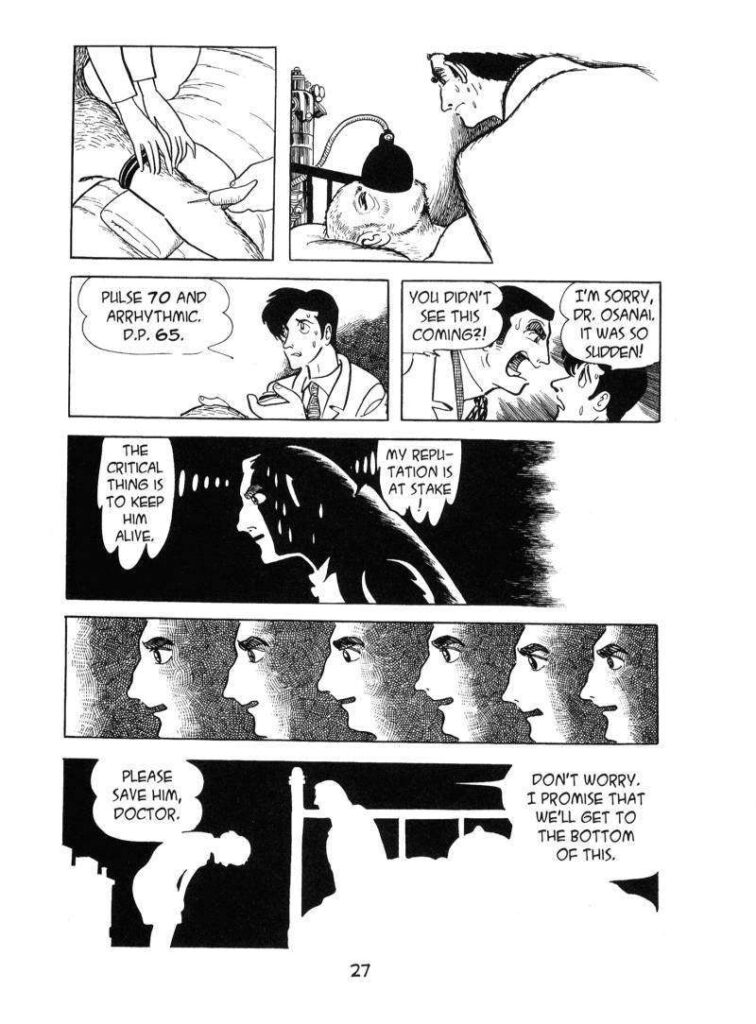

The rather bizarre setup involves two young doctors, Urabe and Osanai Kirihito. (Despite the title, the dialogue identifies Kirihito almost exclusively as “Osanai.”) They assist Dr Tatsugaura, the head of the M University Hospital, in studying a rare disease called Monmow, thought to be endemic to the remote village of Inugamisawa. Nieh renders this name “Doggoddale,” which, though awkward, captures the meaning. One can imagine the locals developed a dog-god cult around the horrifying disease. Monmow begins with intense bone pain and a craving for raw meat, and then causes the arms and legs to shorten, the skull to elongate, and thick fur to burst from the skin. Finally, as these deformations push the body to its limit, the patient dies a painful death.

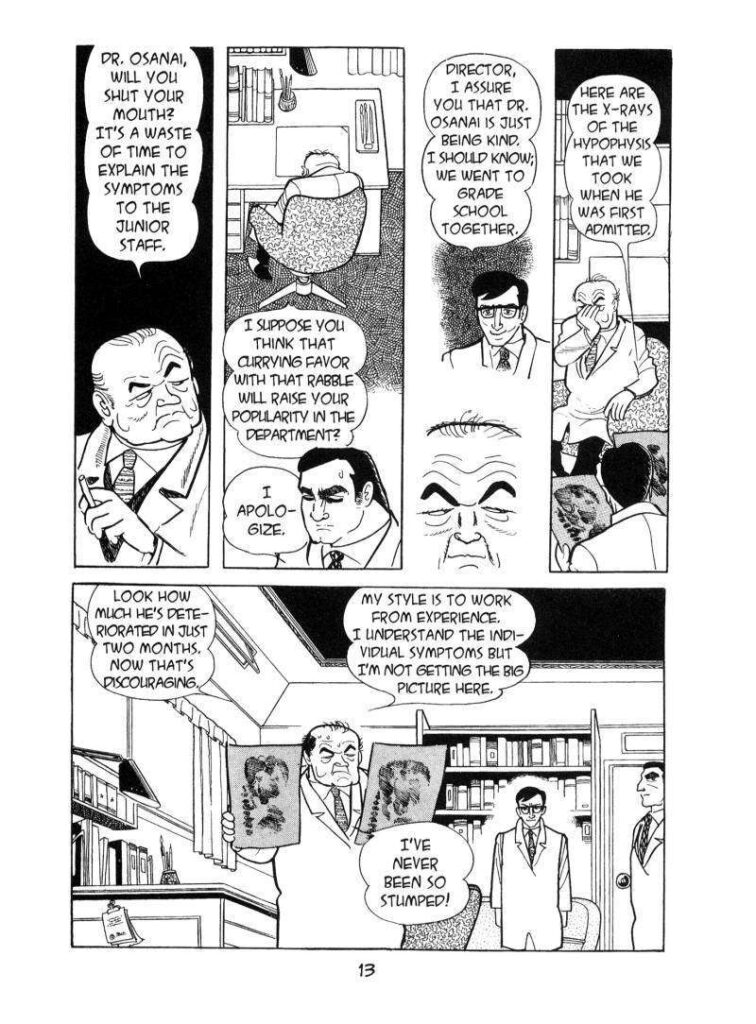

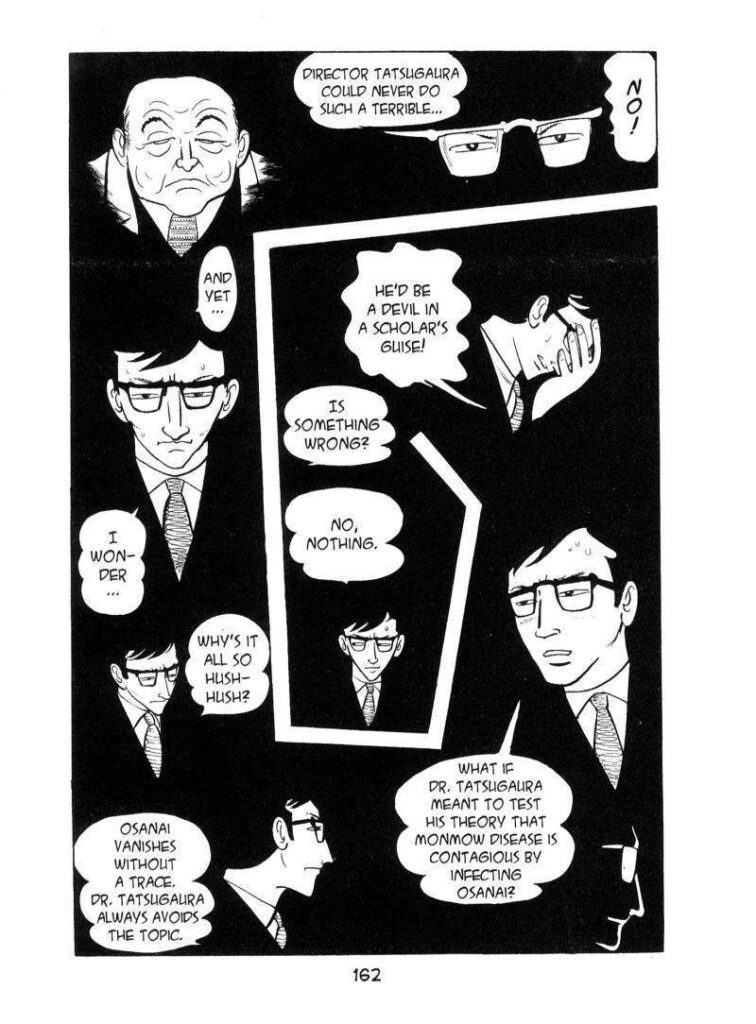

Despite a lack of evidence, Dr Tatsugaura believes Monmow is pathogenic, transferred via a virus. On this hypothesis, he stakes his academic reputation. This is where the book becomes a thriller. Intending to use a presentation on the viral transmission of Monmow to gain the clout he needs to win the upcoming election for chairman of the Japanese Medical Association, Tatsugaura faces increasing opposition. His main opponents are members of the less conservative Young Doctors Association, of which Osanai is a member.

To remove a potential upstart and prove his hypothesis, Tatsugaura uses his connections in a conspiracy to send Osanai to Inugamisawa, infect him with Monmow, and so kill him while gathering data on the transmission of the disease. Clearly, the old man has as little respect for the Declaration of Helsinki as he does for human life. Interestingly, over the course of the story, Tezuka draws Tatsugaura to appear increasingly old.

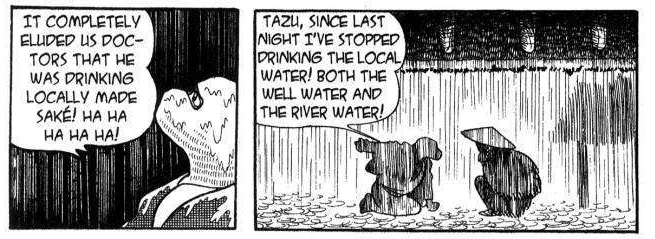

However, with help from his new wife Tazu, Osanai survives Monmow, discovering the true nature of the disease. Not a virus, it is the result of a naturally-occurring poison in the local water table. But, though Osanai’s Monmow stops progressing, it is too late to prevent his metamorphosis into a dog-faced man. From here, a rapist murders Tazu and turns Osanai over to Taiwanese gangsters. The plot spirals out of control, featuring Osanai facing one atrociously gruesome situation after another. This includes being enslaved by Mahn, the man who, for fun, feeds a Pakistani baby to a snake.

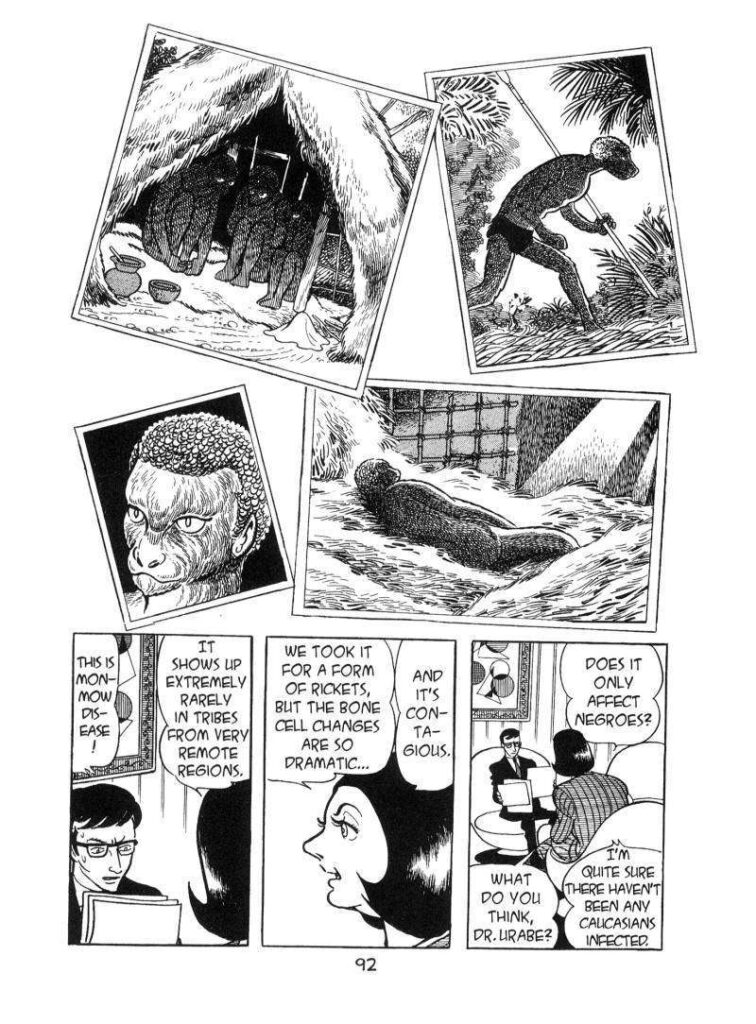

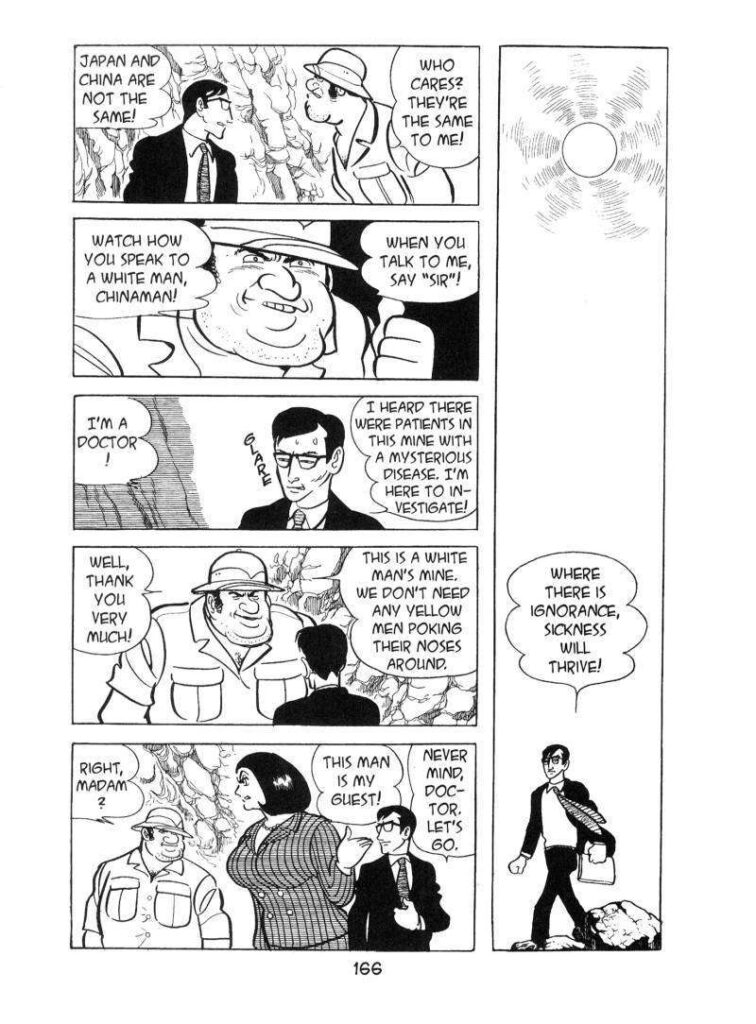

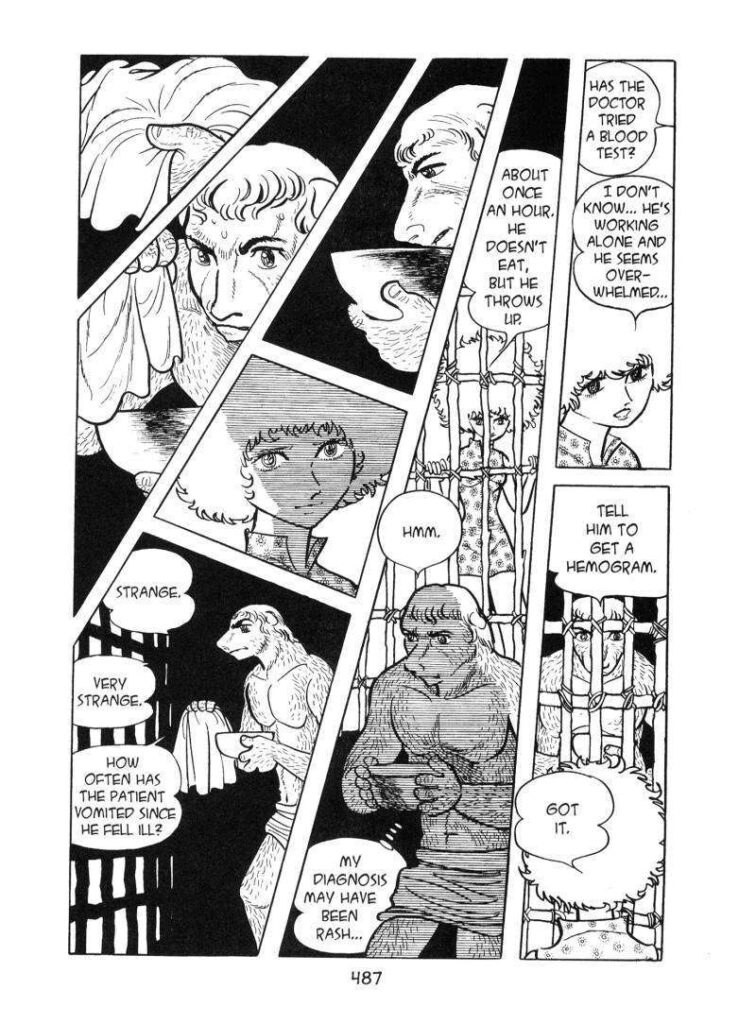

Meanwhile, Osanai’s coworker Urabe begins to suspect that Dr Tatsugaura is not on the up-and-up. Wanting to distract the prying Urabe, Tatsugaura sends him to Rhodesia to investigate reports of Monmow disease occurring among the black population there. It isn’t endemic to Inugamisawa at all, contradicting Tatsugaura’s hypothesis. Urabe becomes entangled with an infected nun named Helen Friese, whom the convent hid for fear that a white woman with Monmow would be too scandalous for their apartheid ideology. “In a white supremacist society like that of South Africa it was unacceptable to entertain the idea of a white person taking on the appearance of a dog or cat” (454).

Enough prevarication. I will jump straight from here to the rape. Tezuka certainly does. It might not be Kirihito’s largest problem, compared to the pacing and structure, but certainly the problem that digs most under my skin is this book’s handling of sexual violence. It ruins almost every character.

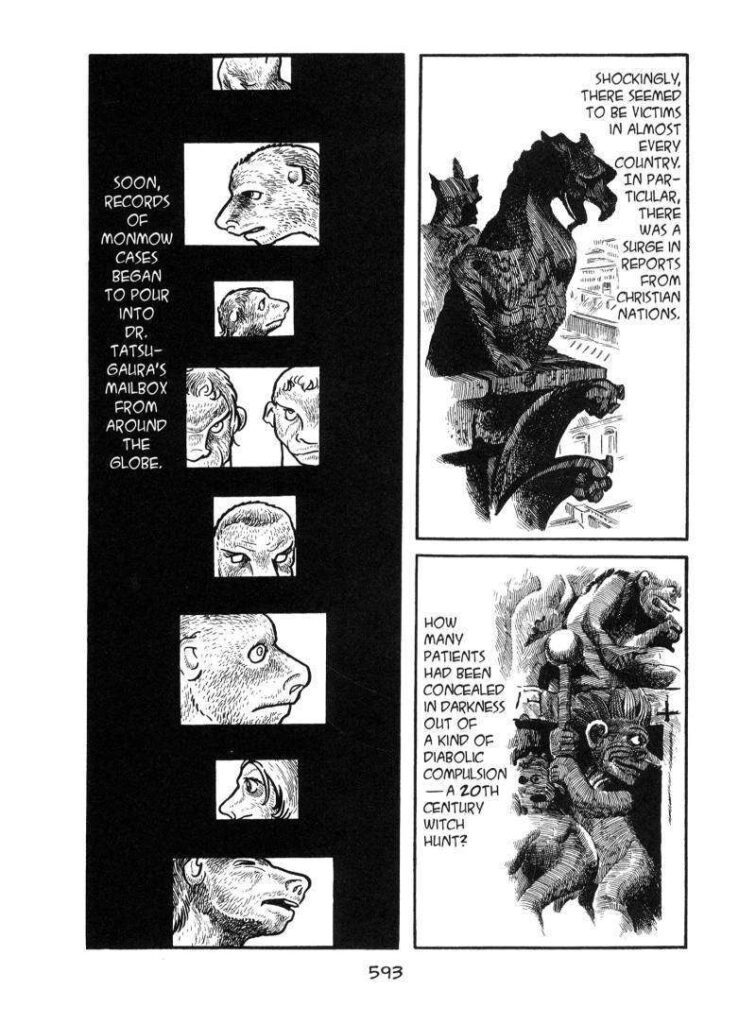

Tezuka grapples with themes of transformation, atavism, and moral degradation. In the same manner Monmow disease supposedly makes people more animal-like, with canine snouts, stooped posture, and a craving for raw meat, humans throughout the story are subject to animalistic violence and impulses. The metaphor is a bit off-kilter, since humans are primates, not canines. But once Monmow is revealed not to be endemic to Japan, cases are reported internationally:

The detail about the “Christian nations” might allude to the crimes of Western colonialism? In any case, there is no correspondence between Monmow and the morality of an individual character. Osanai is almost unambiguously heroic, yet he is afflicted, whereas Mahn is meaner than Satan and gets sick as well. Rather than serving strictly as a metaphor for degradation, Monmow plays into broader motifs of metamorphosis.

The idea of humans degenerating into beasts results in a gallery of discrimination, racism, deception, depravity, treachery, and brutality. There is the orphan Mahn, so impoverished he eats earthworms to survive, who grows rich and uses his immense fortune to torture, rape, and murder the poor for being what he used to be (219). There is McCracken, the racist abbot who attempts to murder Helen and Urabe rather than have his apartheid ideology challenged (171). There are the Taiwanese villagers who loathe the Japanese dog-man Osanai enough that, rather than give up their bigotry, they let their own elder die (512–513). What sets the rape apart from these other subjects is its jarring disconnection from the rest of the story. I have to wonder what the hell Tezuka was thinking!

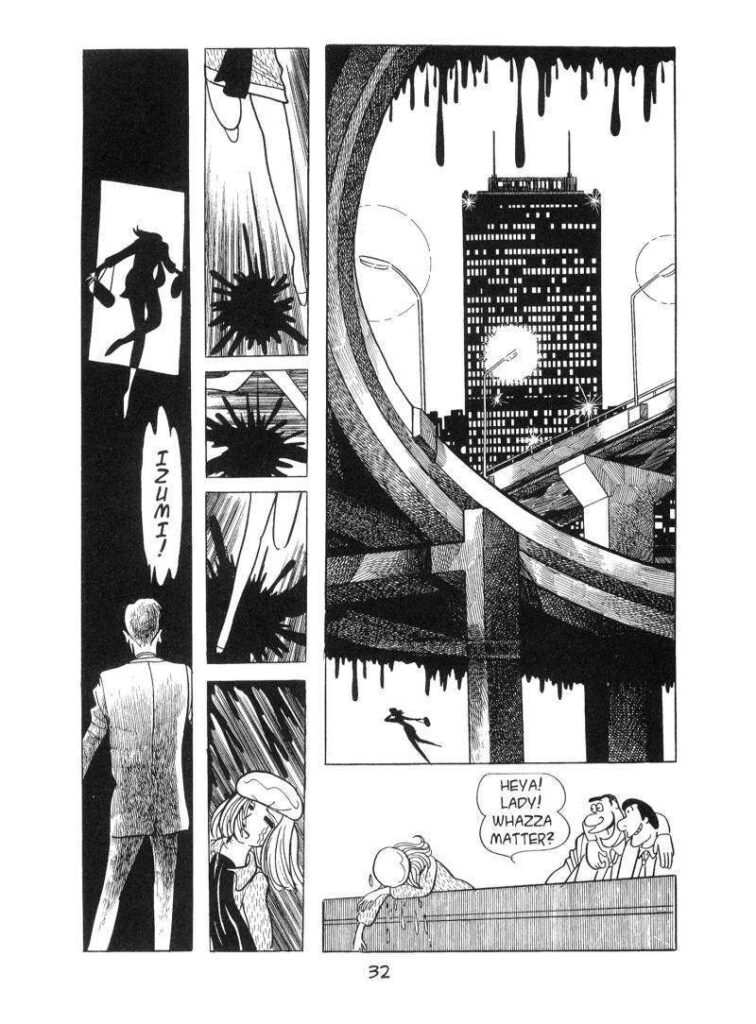

One of the last incidents in Chapter 1 is Urabe raping Osanai’s fiancé Izumi. Before this point, Urabe is established as a lifelong friend to Kirihito: “I assure you that Dr. Osanai is just being kind. I should know,” says Urabe. “We went to grade school together” (13). This is the first thing we learn about Urabe. The fact that he could go on not only to lock a screaming woman in a room and rape her, but that he could do this to his lifelong friend’s fiancé clearly establishes Urabe as an irredeemable bastard. Or so the reader might think. Tezuka makes the scene visceral, depicting the very overpass dripping as though with blood while Izumi runs crying along it. But nothing comes of this.

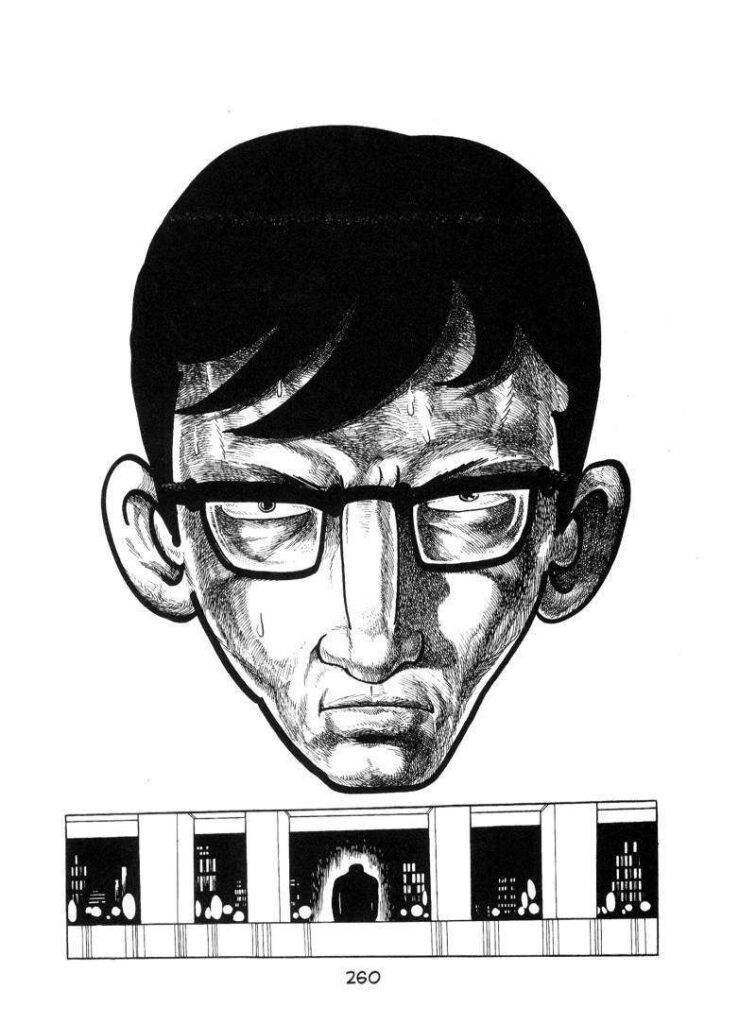

In Izumi’s next appearance one page and probably one day later, she is fine. There is never a hint that Izumi mentioned what happened to Osanai, who continues to think of Urabe as a true friend to the end of the book. Tezuka goes on to devote half of Kirihito to Urabe’s quest to rescue Osanai. In Chapter 7, when Urabe returns from Rhodesia, Izumi follows him from the airport and behaves as though they are buddies (261). She does not hesitate to spend time alone with Urabe, engaging in intimate discussion about Osanai. There is not an iota of distrust or resentment over the violent rape. I should add that Urabe tells himself he performed this rape out of love for Izumi: “If it wasn’t for Osanai, you would understand how I feel… But I couldn’t betray Osanai…never… I’m too weak…” (264). Sorry, jackass, you already did betray him when you raped his fiancé. Also, two pages later Urabe sexually assaults Izumi again. Nonetheless, she continues plotting with him to find Osanai, meeting with him in secret repeatedly. Izumi’s behavior is so baffling I genuinely think Tezuka might have forgotten the events of the first chapter. Maybe women were so abused back then they had much lower expectations in general.

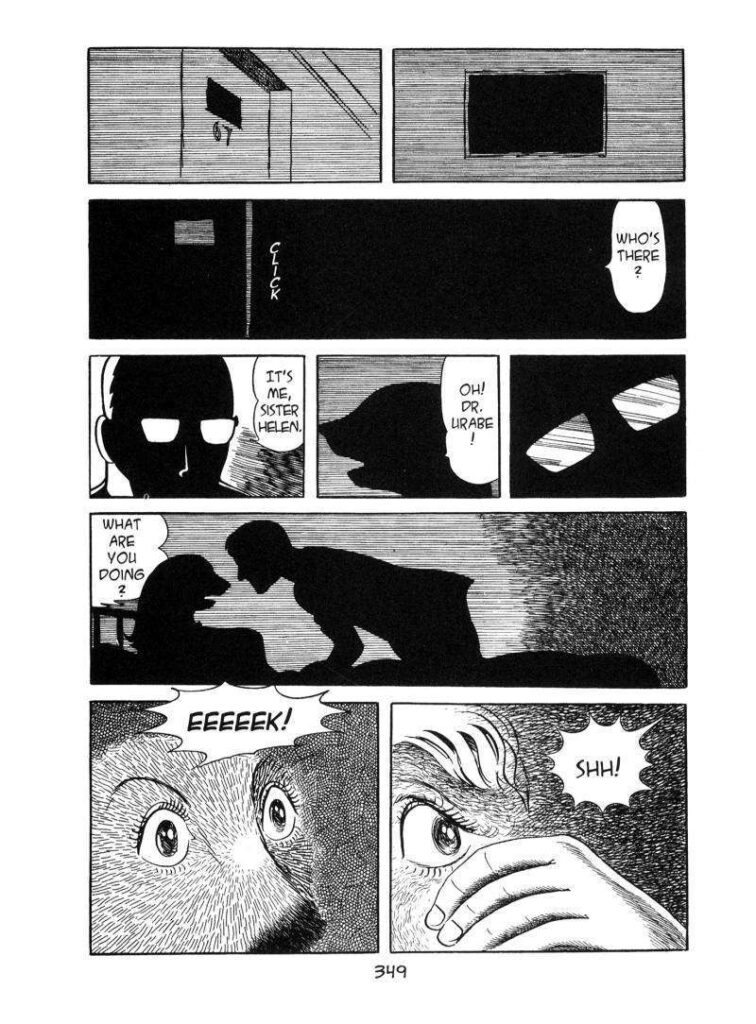

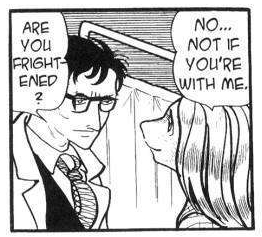

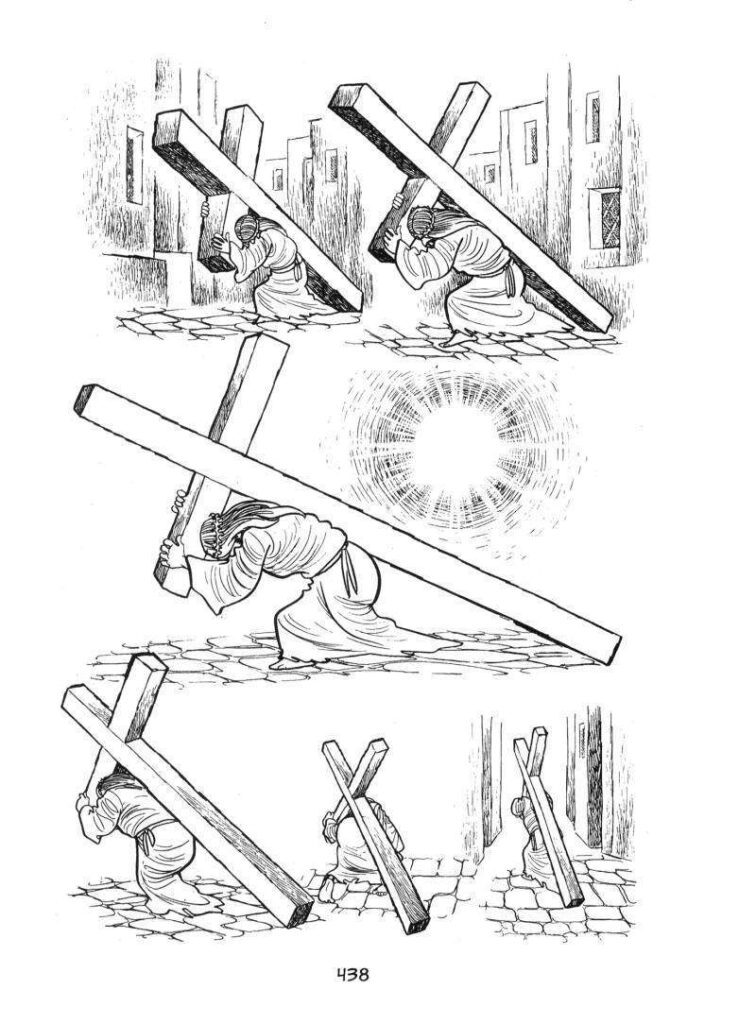

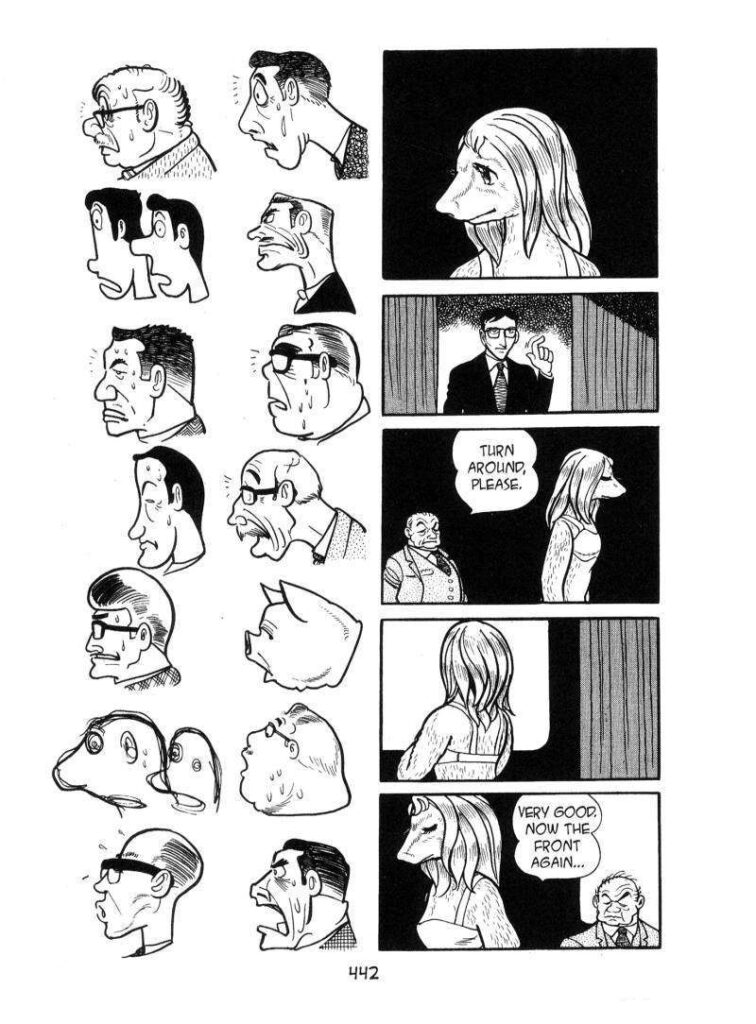

But this is not the end of it. Urabe goes on to rape Helen (349) and later re-traumatizes her to explain how much he actually loves her and wants to make up for what he did (406-408). Helen, naturally, falls in love with her rapist who coerced her into stripping in front of an audience at Dr Tatsugaura’s conference. So horrific are both these torments to Helen that she endures them, crying profusely, only by evoking her faith to liken her tortures to those inflicted on Jesus Christ (437–438). Severe suffering is what we’re talking about here. On page 626, after all the trauma, this seemingly unironic exchange left me laughing with outrage:

URABE: Are you frightened?

HELEN: No… Not if you’re with me.

Perhaps Urabe is meant to be a suave manipulator, deceiving even himself as to his motivations, and Tezuka wants the reader to be disturbed at this abuser controlling Helen. But nah. It is rare that a book gets this much of a rise out of me! I haven’t been this disgusted since Robinson Crusoe, except there I expected the awfulness, and the characterization was internally consistent if nothing else. At several points, Kirihito’s rampant misogyny so repelled me that I meant to stop reading. Whether the rape in something like Berserk is in good taste is another discussion, but there a survivor does not go on to pal around with the rapist like nothing happened. Indeed, I did quit reading Kirihito. On multiple occasions I left this doorstop of a comic languishing in my book pile for months. Wading through the mess took me almost a year. Also, Tezuka draws the black characters in Rhodesia in an offensive blackface style, but that was, unfortunately, pretty normal for comics in Europe and the United States as well, unlike the sexual assault nonsense. Just makes the whole thing even more of a disaster. Kirihito did leave me panting like a half-beaten dog man, but not in the way I expected.

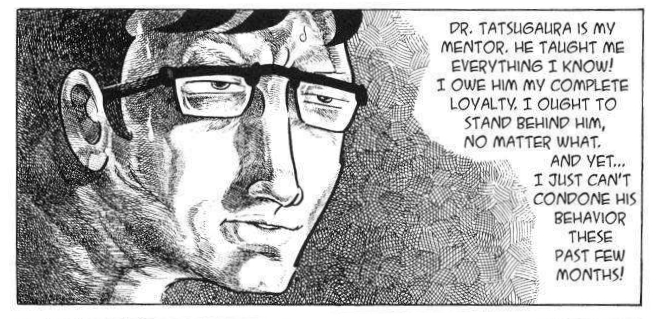

Best I can tell, Tezuka depicts Urabe as a serial rapist as a manifestation of the character’s other psychological problems. The tension between his extreme distrust and professional obligations to Dr Tatsugaura, along with an inability to open up to women, cause him to lose control of himself. If the hierarchies that embroil him leave Urabe unable to control his own life, he, to avoid admitting his lack of social power, can control and hurt those weaker than him in a manner analogous to how Tatsugaura abuses his underlings.

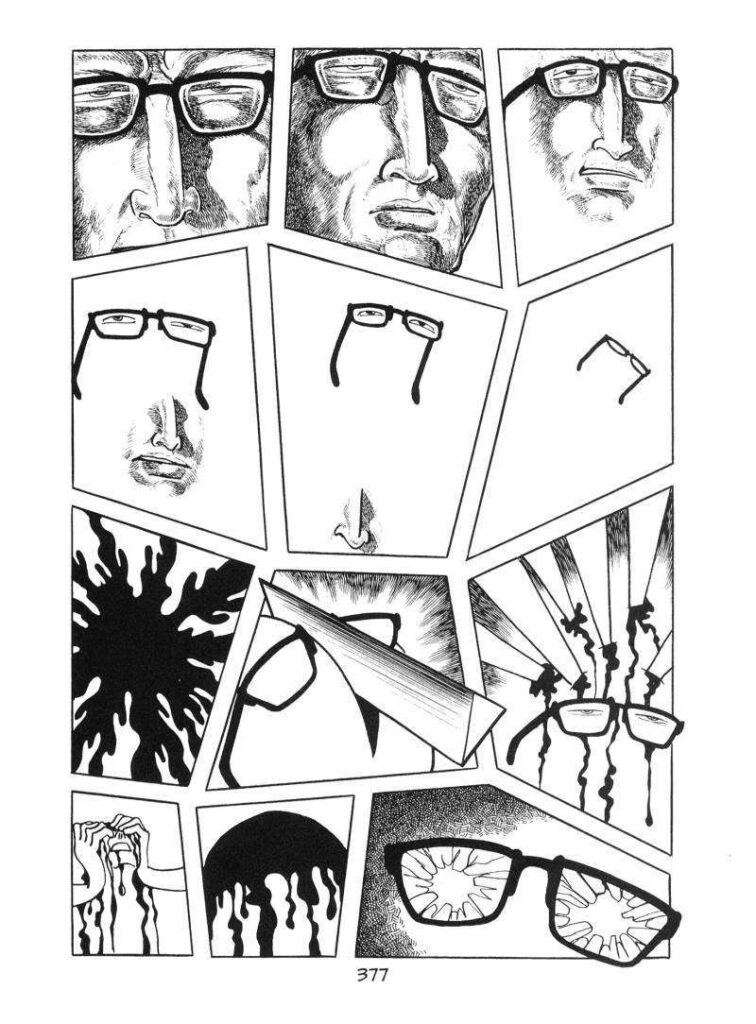

Though a psychologist diagnoses Urabe with “a typical case of schizophrenia” (599), whatever that means, best I can tell Urabe shows no symptoms of it. The “delusions” Urabe supposedly harbors are the entirely correct suppositions that Osanai is alive and that Tatsugaura is responsible and suppressing evidence to further his own academic career. The more interesting aspect of Urabe’s psychology is the obsession he develops with Helen after he rapes her. More specifically, out of guilt, Urabe develops an obsession with saving Helen. He wants to free her from Tatsugaura and find a surgeon who can make her look human again. This obsession is spiritual in nature: “My sin my sin I must atone” (376). Seems some of the nun’s religiosity wore off on him. Urabe’s story, with overtones of Christian salvation, is apparently one of redemptive change. Jesus might forgive, but generally there is an understanding that the sinner must also stop sinning, right? Urabe never makes amends.

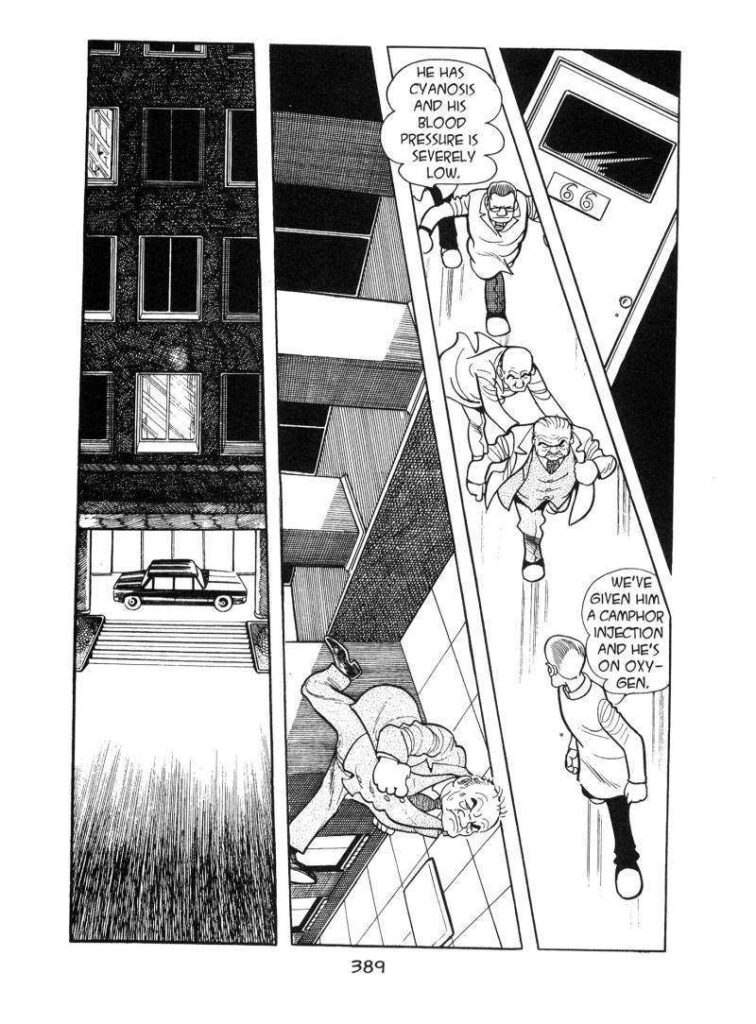

Urabe does nothing. The story of this loathsome scumbag takes up a little over half of the total eight-hundred twenty-two pages—more of an ode to Urabe than Kirihito—but has zero payoff. In Chapter 14, having succumbed to guilt and impotence, Urabe kills himself by jumping in front of a truck. At that point, he has not saved Helen, not exposed Dr Tatsugaura’s plot, not redeemed himself, and not located Osanai. Every single plot thread goes unresolved: a cardinal writing sin, as far as I’m concerned. Osanai’s meeting with Helen in Chapter 17, though a good scene, does not justify devoting so many pages to her and Urabe. Instead of requiring rescue or the details of the conspiracy exposed to him, Osanai figures out the whole plot instantly upon reading Tatsugaura’s report in Chapter 16 and returns to Japan to set things right.

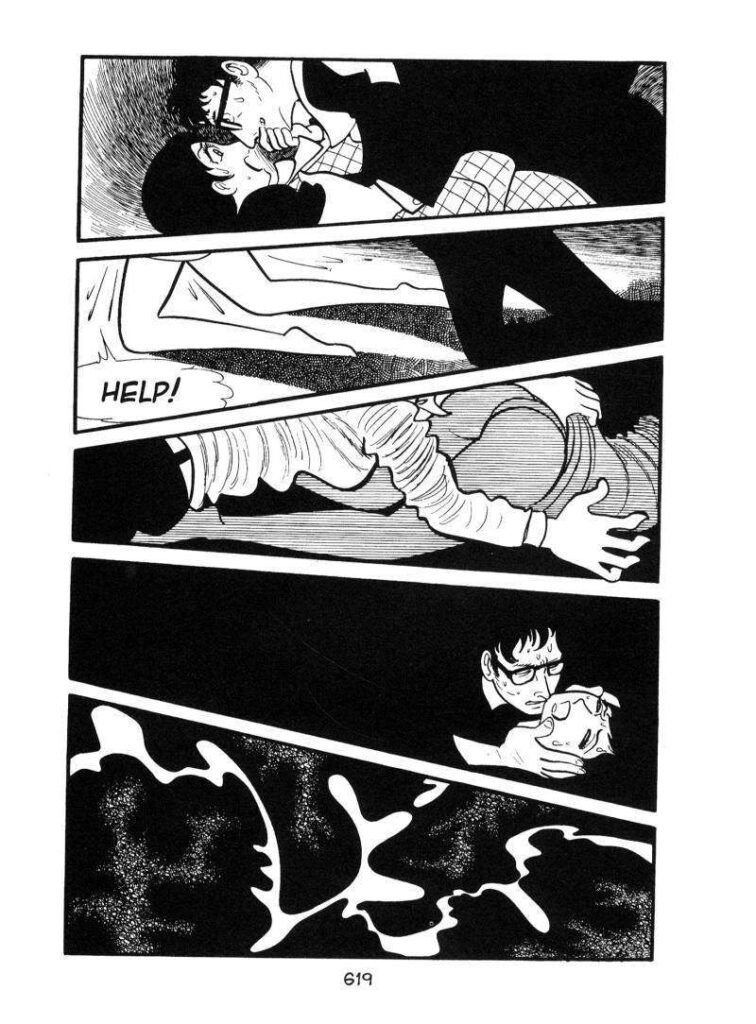

Not only useless to the plot and hence earning no sympathy from the reader, Urabe undergoes no redemption. He never relates to Helen as a person but only as a tool for his ego. One of his final actions is to rape Izumi again, this time more graphically (619–621). Yeah, let’s really give this woman’s meaningless suffering a good wallow! Yet the story treats Urabe as though his wretched life, a life spent abusing his patients and stabbing his best friend in the back, ended well. Helen gives birth to his child, and the infant is not dog-faced. Does Tezuka have the audacity to liken Urabe to the angel who impregnated the Virgin Mary? That might seem like an interpretive leap, but the Christian portions of the book are extreme and unsubtle enough to support it. In any event, this resolution and Osanai’s continued love for Urabe confirm that the treacherous serial rapist is not meant to be read as manipulative and Helen’s love for him as a coerced mark of abuse.

Urabe’s half of the book—so most of the book—is not only offensive, but a waste of time. This could be the point: an abuser, no matter his intentions, cannot really do good in the world. However, if that is what Tezuka intended, the story fails to give that impression. It just feels sloppy. I hate Urabe in a way I rarely hate fictional characters, and Tezuka made me suffer alongside this creep for hundreds of pages for no payoff. Made me? Well, I could have put the book down. I do not object to a story about a detestable character in of itself, but I do when the author does not seem to realize the character is detestable.

There is plenty of trauma to go around, though. Osanai is also a rape victim. His half of the book, though not outstanding, drips with more interest than Urabe’s. But no worries, it has no shortage of nudity and violence. Remember how Osanai abandons Izumi for Tazu very early on, and then Tazu is raped and also murdered? Her killer comes back near the end and still offers no motive or explanation for what happened beyond lust: “Don’t know what came over me, but when the woman was alone, I had to have her” (684). But since this hollow character, initially framed as a major antagonist, is another plot thread to nowhere, I will not mention him again.

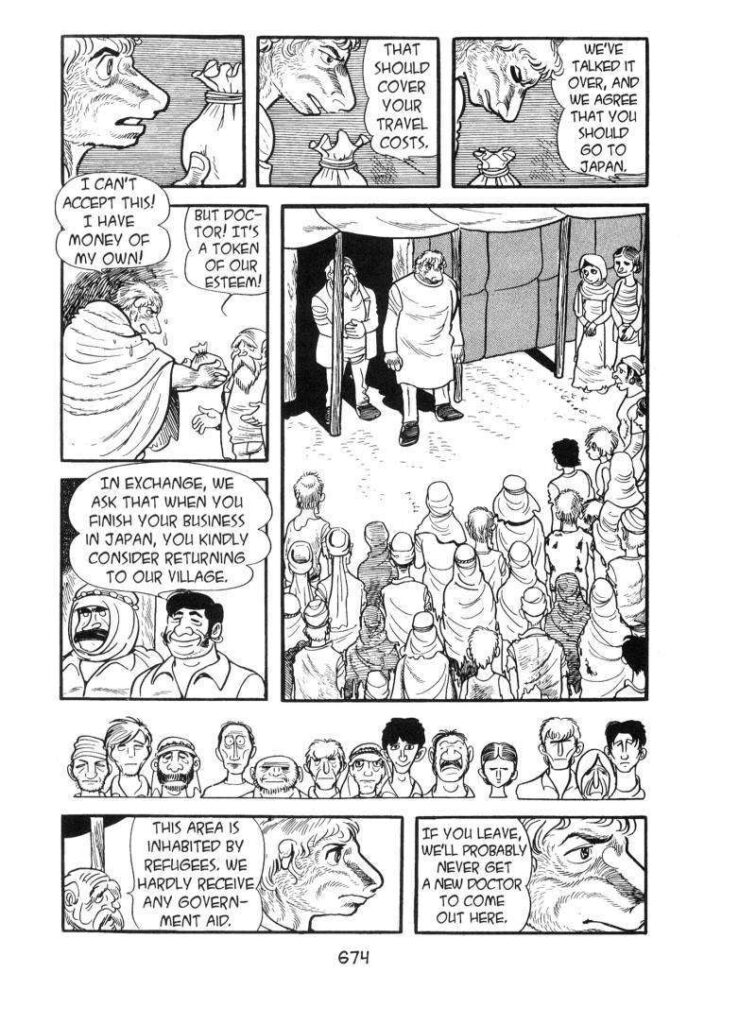

Osanai, though a vengeful atheist, also wants to be like Jesus: “If only doctors were like Christ… with the power to revive the dead just by touching them, or to heal the sick” (555). But, unlike the failure Urabe, Osanai, like Helen, is a Christ figure, suffering for his honorable beliefs when the JSA power structure turns on him and then undergoing trials and temptations in the desert before selflessly healing poor people in a village of refugees. Certainly seems Jesusy to me.

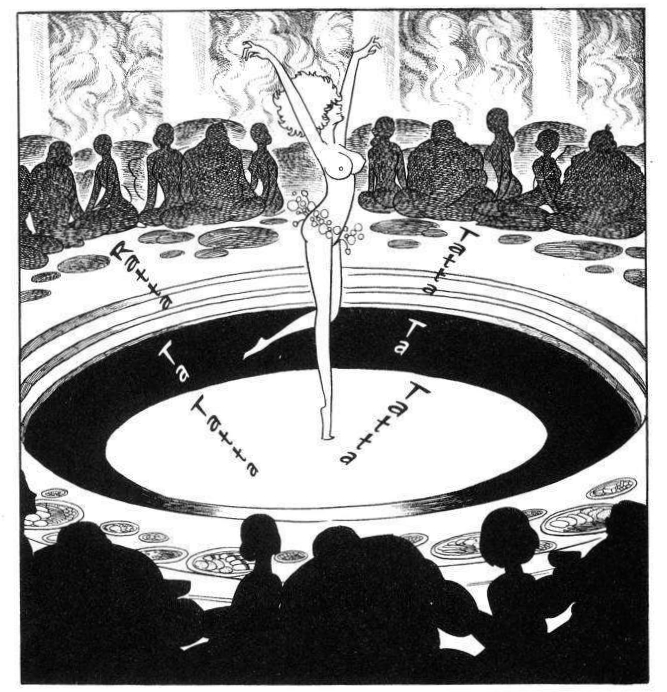

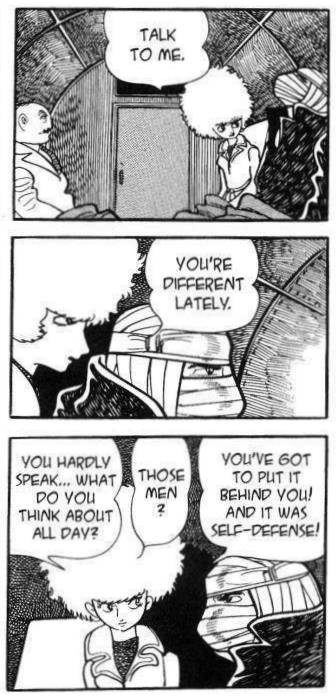

Enough Osanai. Now we reach my favorite character: the sensual sideshow performer Reika, the human tempura. This is not to say that she would be admirable as a real person. Perhaps Reika sticks out for being one of the few people who shows Osanai anything but cruelty (at first) or for being a woman with significant agency who also never gets raped. Or perhaps I just love her poofy hair. My second-favorite character, the German Monmow researcher Dr Manheim, also has poofy hair, so make of that what you will.

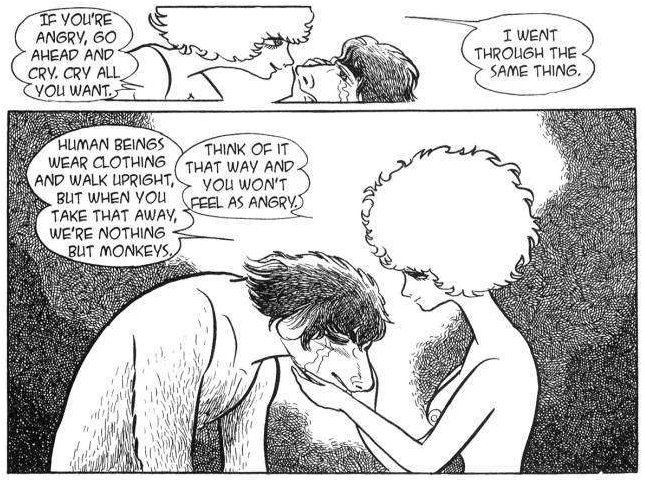

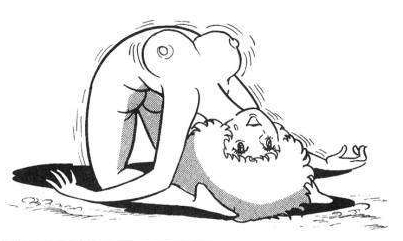

Reika first appears in Chapter 6, set in the depraved nightmare world of Mahn’s palace, where rich men hold orgies while watching poor people perform, suffer, and die. Which sounds kind of like a microcosm of the world at large, but certainly fits in with the “humans becoming beasts” theme. Reika first appears as a nude dancer who contorts like a pretzel before an aid covers her in batter and fries her in a cauldron of boiling oil. Surprisingly, given what else we have seen of Mahn, she survives! It becomes clear Tezuka has more in mind for this character than an excuse to draw tits. After a dog rapes Osanai for Mahn’s amusement, Reika comforts him backstage. She, too, is one of the enslaved. Naked, she takes Osanai’s canine snout in her hands and, shock of shocks, shows him compassion:

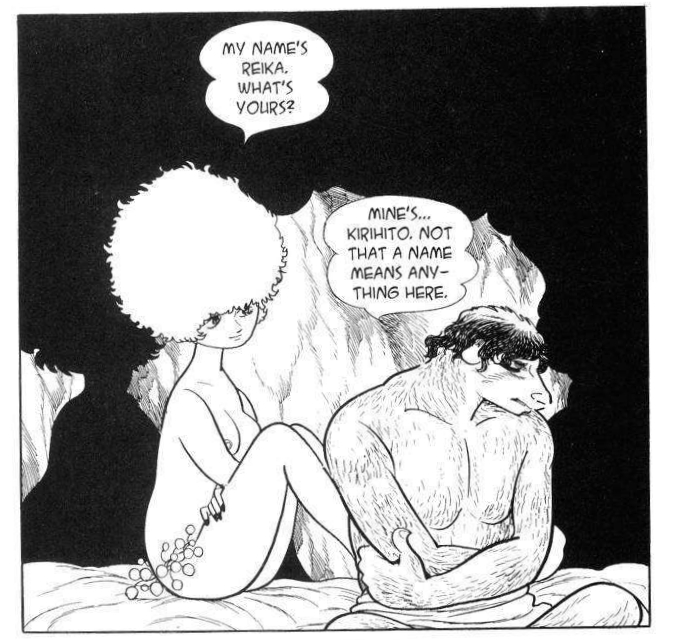

“Mine’s… Kirihito. Not that a name means anything here.”

Subjected to brutal conditions to learn her tempura routine since early childhood, Reika nonetheless retains more compassion and humanity than the well-to-do city-slicker Urabe. This kindness, however, comes clothed (ironically) in animality. Osanai struggles throughout with the question of whether he is still human, but here Reika reminds him that humans are just animals anyway. While this might be a positive message in another context, her sense is that humans, like animals, have no need for dignity. Her perspective is more a coping mechanism than a well-considered philosophical position, a scar from a lifetime of exploitation and near-deadly burns (212). Burns that seem to have left zero scarring, but still.

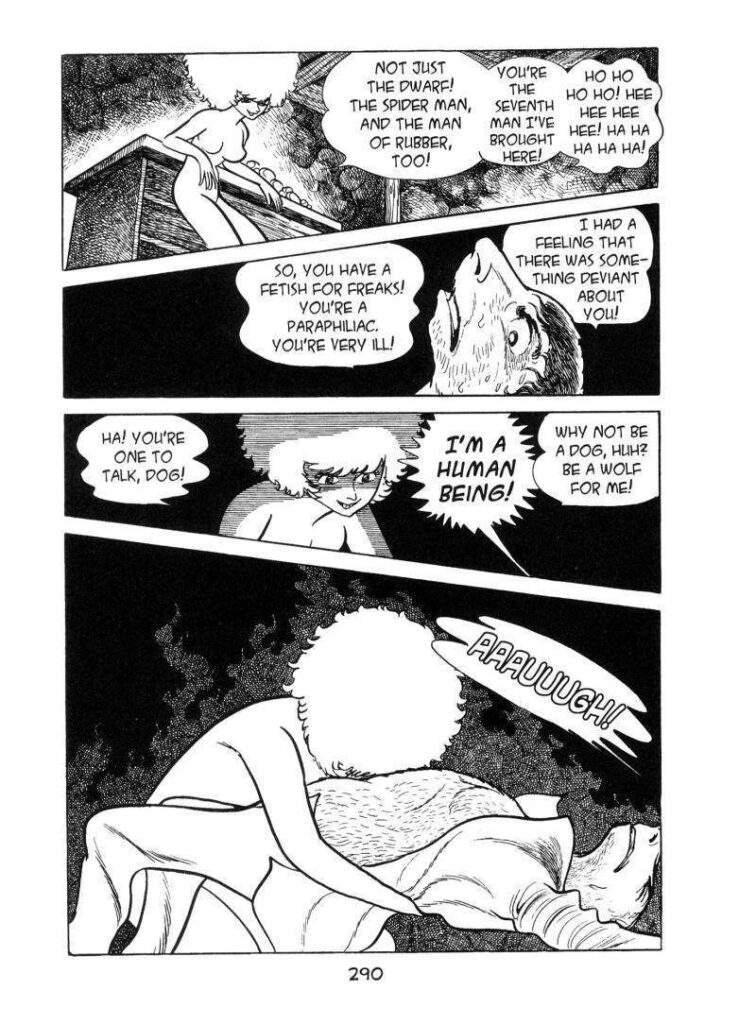

However, Reika takes the animality to heart. It is one thing for Reika to revel in sensual dances, sex being among the few pleasures allowed her, but quite another to be a sexual predator. Yeah, Kirihito is so misogynistic that the only woman who acts on her own agency without falling in love with her rapist is, herself, a perverse sex-crazed rapist! In the finale of Chapter 6, after leftists bomb Mahn’s palace, Reika helps Osanai escape. Under the starry night sky, the two camp in the Taiwanese countryside. Reika, crawling on all fours like a dog, attempts to perform fellatio on the sleeping Osanai, who pushes her off. Sobbing, she shouts that they are “rejects” and “lowlife” beneath concern. Even the circus turned Reika down. The Christlike Osanai forgives the attempted rape. I can accept that the goody-goody hero might be super forgiving, especially since, unlike with Urabe and Izumi, the assault seems to have stopped before anything happened. But this is just the beginning.

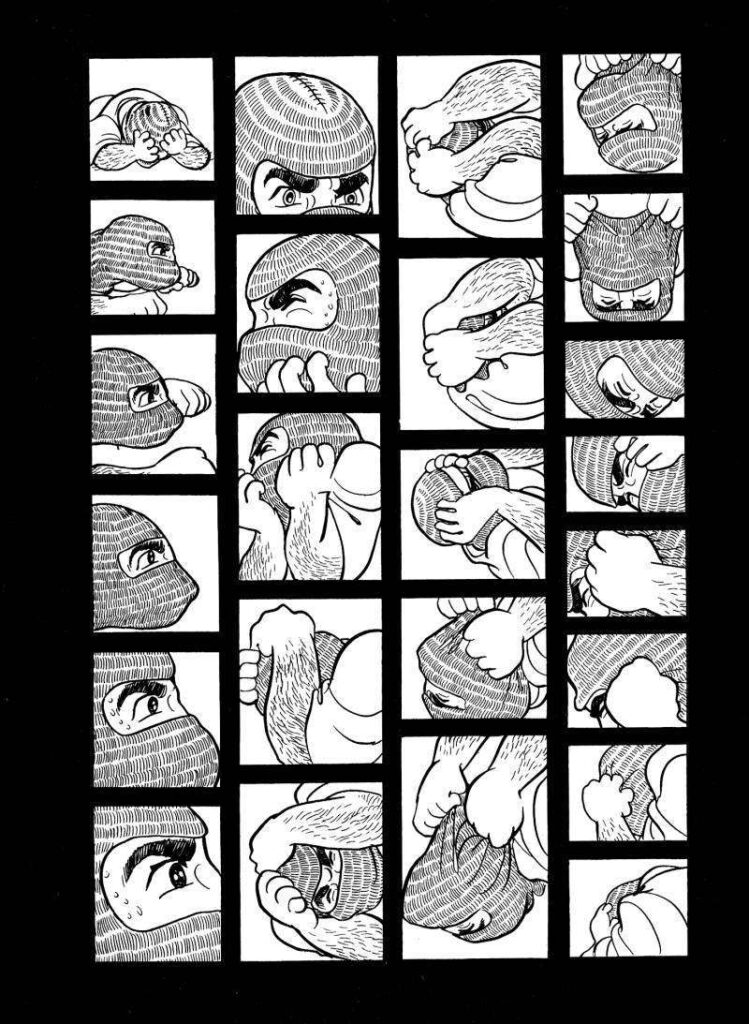

In Chapter 8, Reika tricks Osanai into scaling the remote Mt Sheng to hide out in a small shack. There, Osanai discovers that she previously kidnapped and raped seven other men. Reika lashes him to bed and serially rapes and starves him for forty days (298). Osanai never ejaculates, which might be a bit impressive if he were not so hungry and dehydrated. It is ambiguous whether Reika murdered the seven other men. She claims the last one killed himself. Eventually, Osanai escapes, convincing Reika that she is sick and he will do his utmost to help her like any other patient. But some mountain folk capture the two of them shortly thereafter, caging Osanai and putting Reika to work as a servant.

This sequence is brutal. Constrained, Osanai can only writhe as ants and flies coat his unwashed fur (296). Spending the entire sequence naked, Reika embodies an animal lust, craving Osanai for his body from her fetish for “freaks” out of a sense that they, like her, are rejects, no longer human. Basically, Reika is a rather hateful succubus kind of monster. In a book which treats all its women this badly, I am less charitable than I might be if Reika were just one depraved woman in a cast with all sorts of women. But, as the kids say on the internet, this ain’t it, chief.

As with Urabe, Tezuka spares no effort in depicting Reika as monstrous. To top off her other problems, she is also racist against Japanese people: “Japanese are so repulsive!” (535). While I can make myself like Reika temporarily by putting this scene out of my mind, much as I can temporarily make myself like Urabe, Tezuka may have gone too far. Much as abuse victims may perform similar abuse on others, one can easily imagine that the abuse Reika performs reenacts that visited on her: seems doubtful a semi-enslaved stripper exactly had her own bodily autonomy respected. Urabe, in some sense, acts out his abuse on others as well, but as he dealt with abstract social and professional pressure instead of literal slavery, Reika remains more sympathetic. However, the redemption narrative works better for her character. Unlike Urabe, the human tempura actually does change. Though treated like an animal, Osanai proves his belief in human dignity and worth, even the dignity and worth of a moneyless mentally ill sexual criminal sideshow performer. The realization that such good is possible allows Reika to regain some dignity. Respect for herself leads her to show respect to Osanai. After this scene, Reika, no longer an animal, starts wearing clothes. She returns the favor of Osanai’s compassion by helping him escape from the villagers with assistance from a Taiwanese doctor.

When she and Osanai end up stranded in the Syrian Desert, it is Reika who has to plead with Osanai about the sacredness of human life (547–548). Traumatized, Osanai begins doubting his humanity. Person after person, including Reika, abuse Osanai as subhuman. In Taiwan he fails as a physician and kills two men. For him, a man who is supposed to save others, this is most damning.

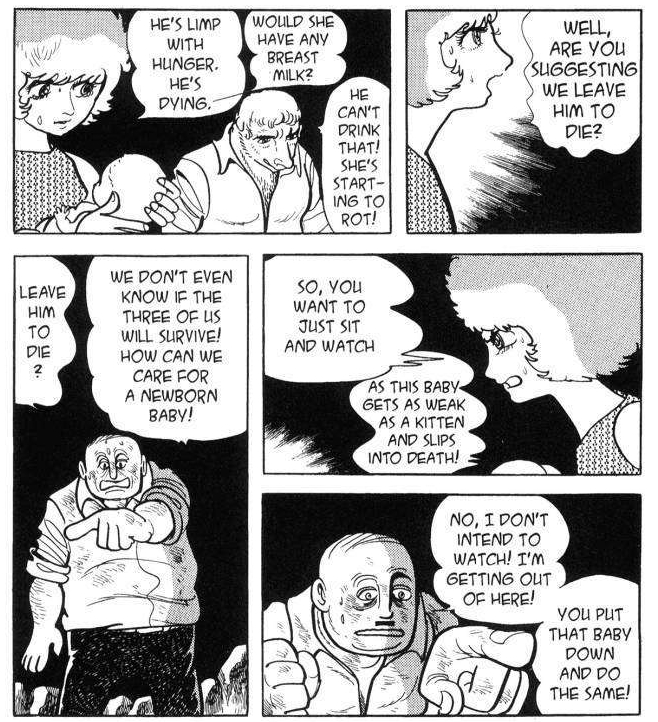

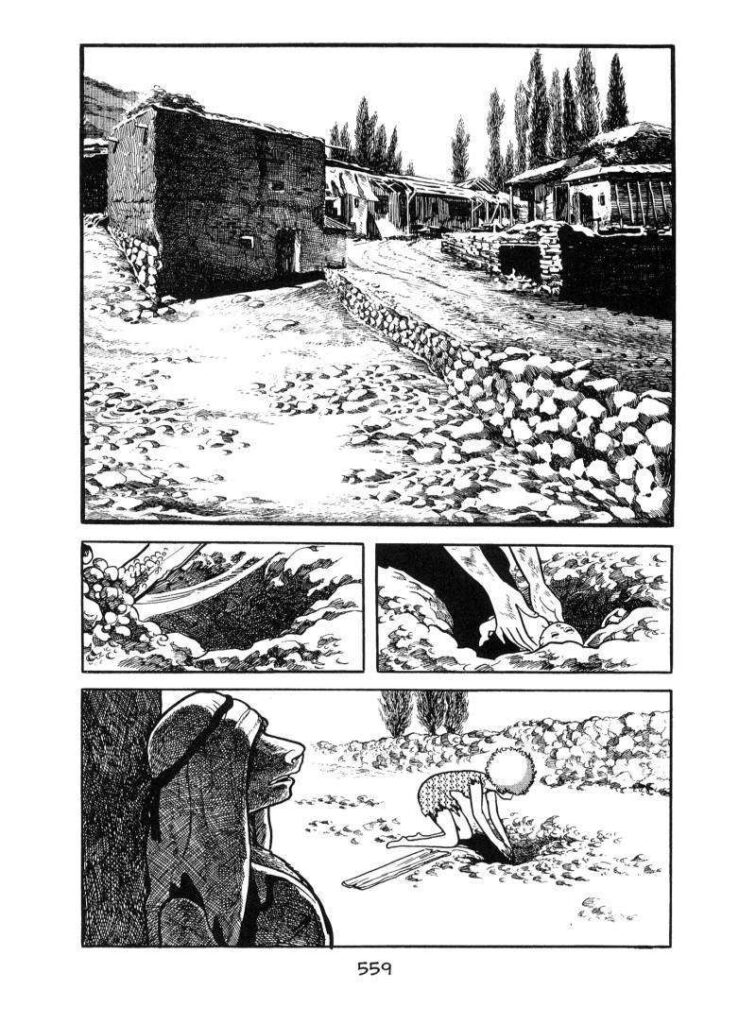

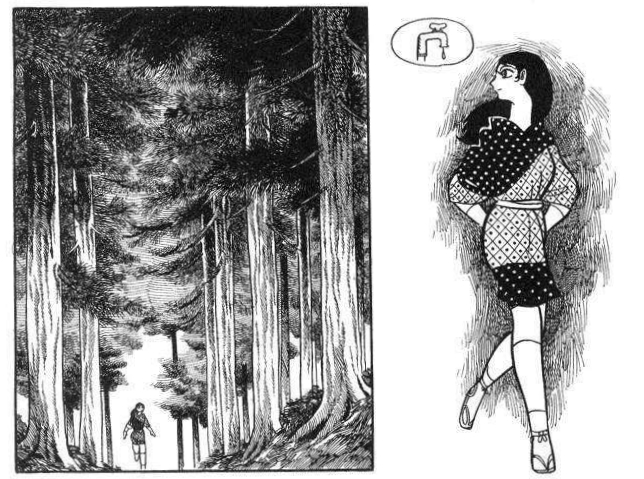

Yeah, after Osanai and Reika escape Taiwan, Palestinian terrorists hijack their plane. Afterwards, an Israeli (probably?) bomber kills the Palestinians before they can drive their prisoners back to civilization. This leads, in Chapter 12 and Chapter 13, to the best sequence of the book, featuring Osanai, Reika, and the pathetic Japanese oil baron Murakami wandering the desert.

The artwork makes the landscape so desolate, the characters so grimy and sweaty, the heat as sweltering as the emotions. Chapters 12 and 13 are, fittingly for gekiga, cinematic in the best possible way. Eventually the splintering group finds a dying baby, his mother shot in the head. Osanai, having murdered already, believes he can heal people no longer (564). Despairing, he attempts to strangle the infant, but Reika, recovering her own humanity, rescues the child (547). Reika carries the infant for hours, until he dies. When Osanai struggles with his faith, not in God but in humanity, Reika has made up her mind to believe in people again and seems pained that the person who restored her human dignity is losing grasp of his own.

In Chapter 13, pressed for cash and facing the locals’ xenophobia, Osanai, Reika, and Murakami struggle to get by in some Syrian town. It is ridiculous, in my opinion, that when they cannot pay for a few sips of water, the merchant’s instant reaction is trying to kill them (558). Surely a cynical, Scrooge-like miser would force them to work it off? Tezuka just wants the story to be dark, dark, dark even when it makes little sense. This random businessman is substantially nastier than the airplane hijackers! Though that might be true to life.

Osanai, emotionally incapacitated, lazes around while Reika and Murakami try to buy food and get turned down again and again. I thought Islam teaches charity? Nobody in the whole town will help them? Anyway, because Osanai now refuses to work as a doctor, Reika turns to prostitution up until Osanai attacks her client. Although Osanai earlier claims he had no sexual or romantic interest in Reika, here he shows the true colors of his complex emotions: “I’ll kill you if you touch my Reika again!” (568).

When a circus passes through the town and Osanai refuses to let Murakami display him as a sideshow freak, Reika persuades the pimp to help her put on the human tempura routine (575). But these men are not professionals, and their spatula breaks. Reika boils to death in hot oil. Chapter 13 ends with Osanai weeping, embracing the burnt batter that encases her remains. I almost, again, stopped reading there. Without Reika, who cares? She was the only character I felt any investment in. You could call it karma for her earlier transgressions or a judgmental punishment for taking her clothes off for the first time since her transformation on Mt Sheng. In any case, it is Osanai who drove her to this. Had he been willing to heal people or let spectators gawk at his dog-face for money, or if he had not been creepily possessive when Reika tried servicing a john, she would have lived.

I wish Tezuka had written Ode to Reika instead of using her as eye candy to fridge for yet more melodrama in the most cruelly ironic way possible. Especially since Tezuka abandoned Izumi as the female lead long ago, and the story concerns salvation and transformation, why couldn’t Reika finally escape from animal brutality into a better life? Things work out for the oafish Murakami, but not Reika?! (Murakami vanishes with no explanation, but the implication is he returned to Japan.) What, did Tezuka want Osanai to end up with the forgettable Izumi, so he had to kill every single other woman the doctor meets? If so, this is all the more of a slap in the face, as Osanai later breaks up with Izumi. When, after about seventy pages of Urabe and Tatsugaura nonsense, Osanai next appears in Chapter 16, he has a new assistant, Ali. While Ali is fine, why couldn’t the doctor’s helper have been Reika? This would not substantially change the plot and would serve as a better story. Reika already works as a nurse for Osanai and the Taiwanese doctor in Chapter 12. Osanai could have remained loyal to the late Tazu and just, you know, not fucked Reika. Men and women could be platonic even in the ’70s. It would have been perfect, a true metamorphosis, from depraved sideshow performer to self-realized medical practitioner. Well, maybe if Reika had not been quite so nasty in her stint as a serial rapist! I am not certain someone could come back from that.

Even Tazu was more interesting than the protagonists we got! Here is a beautiful woman from the back of beyond who participates in Dr Tatsugaura’s conspiracy to kill Osanai. She appears nude before a stranger to seduce him. This lady has guts. What did the mayor tell her to put her up to this? Surely Tazu does not know about Tatsugaura, the ringleader. After initial rejection, Osanai accepts her as his wife, symbolically giving up an urban life that Tazu never knew. Osanai is almost like an alien to an Inugamisawa native like her. What does Tazu learn about him and he about her? As Osanai struggles to treat him, her father dies of Monmow disease. Then Osanai, too, is infected. To Tazu, operating in a universe of folk beliefs, this means the dog deity, having possessed her father, has now moved on to her new husband. Tazu legitimately cares for Osanai and seems to fall in love with him, offering unconditional support even once he makes up his mind to escape Inugamisawa. There is so much room for drama and complexity: Tazu’s conflicted emotions, sexual experiences, exploring the world beyond her village—the psychology of the religion surrounding the disease, the clash between the folk and scientific paradigms—suspense over what Osanai will do when he learns the truth about her—over how she will react when she realizes how she helped Tatsugaura—over what will happen when Tazu and Izumi meet. But Tezuka barely does anything with Tazu before having her raped and killed on page 129. Osanai mourns her on page 202. Then Tazu is never mentioned again (I think) until page 684, after which Osanai tells Izumi they can never be together because his real wife is Tazu. What a waste of a character.

If the racism in Kirihito did not emerge in a vacuum, neither did the misogyny. I can absolutely believe that people like Urabe existed. The Me Too movement has uncovered an absolute mountain of festering abuse, but that abuse is nothing new. The powerful using their authority to carry out serial rape has been happening for decades and centuries, just without social media to cast light on it. Hell, in some times and places, harems were a legitimate signifier of a rich man’s power. In depicting a respected doctor as a habitual rapist who abuses every woman he meets, Tezuka may have reflected a reality. But we should also keep in mind that mainstream Hollywood movies were still playing romantic music over rape scenes as late as 1982. Let’s not pretend misogyny isn’t still common in pop media, even if we live in the age of shows and blockbusters that at least tend to be more inclusive in casting. While questionable gender politics blight Kirihito and much of Tezuka’s other work, they reflect a broader current poisoning hegemonic pop culture across the world.

The chief issues with Kirihito result from two primary features. The first is that this was a serialized work. While Tezuka had no shortage of experience with serial fiction, stories written in this manner, if approached as a whole text and not as individual episodes, tend to suffer from atrocious plotting and pacing. Much of what makes Kirihito nonsensical stems from characters going totally off the rails. According to Tezuka In English, Tezuka wrote: “Novelists often say… their characters get out of hand, and this happens with manga too. When I was writing… Ode to Kirihito… [Osanai] started to wander on his own. Originally I planned to have everything happen in a smaller circle, but the story came to have an unexpected turn as many characters joined the scene, and I finally gave up and let the hero act out his own story.” While Tezuka believed he had resolved the story successfully, and I guess he did if success means “it stopped,” he was merely intellectualizing why the book is bad. Oh, I couldn’t help that the characters’ behavior makes no sense and that half the plot threads go nowhere! It’s their fault, them, the people who aren’t real and whom I control absolutely! Granted, in my own fiction, I often have the sense that the characters end up developing in ways I didn’t quite expect. But the inability to revise is the great risk in serialized fiction, and I am too irritated with Kirihito to feel generous.

The second fundamental flaw is he author’s probable inexperience with gekiga. In 1968, just a couple years before Kirihito, Tezuka had serialized the charming Dororo, a transitional work, darker than most children’s fare but far from X-rated like Cleopatra (1970) or the adventures of the dog-faced doctor. Tezuka was still fresh from all-ages goofiness. And all-ages versions of racism and murder. Swaths of Kirihito come off as juvenile attempts at “maturity.” What if a hero was also a serial rapist? What if Osanai violently attacked his friendly assistant Ali? What if I put in multiple dead babies? What if I quote the Bible and throw Christian and Buddhist imagery around? What if every single woman is raped and/or dies gruesomely? How many boobs do I need to draw to prove how grownup I am? I feel like I mistook a teenager’s exercise in edginess for a novel worth taking seriously, and this is what left me so disappointed. (Actually, Izumi’s mother is never raped, nor the Rhodesian doctor Urabe meets nor the nurse who poisons Tatsugaura.)

I would be remiss not to acknowledge that Tezuka, though super sexist and bad at writing, was, by 1970, a master storyteller. It is not the same as being a master writer. He earned his title as the God of Manga. The artwork is excellent, the characters rich with cartoony life, the linework solid and expressive, the panel layouts simple and elegant yet varied. Sometimes the artwork alone lends irrelevant moments a sense of profundity. Tezuka experiments with different modes of visual storytelling, using his medium in a manner few artists did or do, especially in the ’70s.

Outside of hanging around with her rapist and attempting suicide, Izumi, I admit, has an ounce of agency. Near the end, she denounces her father, Tatsugaura’s toady, for neglecting her wellbeing to the point of wanting to conceal her rape to defend his boss.

“Is that how much you care about Dr. Tatsugaura’s reputation, Daddy? You value it more than your own daughter?”

“If this gets out, there’s no telling what effect it’ll have on the JMA election!” he argues, as his child sits naked, wrapped in blankets, mere minutes after Urabe had his way with her (624). She rightly smacks her old man. About time. Kirihito closes with Izumi running away from home and boarding a plane to find her fiancé in Syria. Though Osanai insists he cannot be with her, she, full of newfound confidence for having finally stood up to her parents, to the same abusive power structure that destroyed Urabe and led to her repeated rapes, is determined to find him after all (820). Though no means no, Izumi.

“Izumi set off to distant lands to find Kirihito… What was the future for the two to be? Perhaps the pages of another tale” (822). Thankfully, Tezuka never wrote a sequel to this mess, so far as I know.

In any case, people can rise above monstrousness despite the depravity of the world. For every hypocritical fanatic like McCracken, there is a selfless doctor like Worthinton. For every depraved act Reika commits, there are those kindnesses she achieves when she regains humanity. Though Helen is shot, raped, and humiliated, she never wavers in her faith and commits herself to helping a village of impoverished miners whom materialistic doctors like Tatsugaura will not. And despite his constant abuse and torture, Osanai manages to inspire hundreds of disabled people (807) and give Syrian refugees assistance nobody else in the world ever would. But also misogyny.

I wrote that Tazu is a waste of a character. I might add about Kirihito: What a waste of a book! To me, art that is terrible frustrates less than art that could be great, but then swerves off a bridge. As an artist, though, I often take inspiration from failure. This story did not do what I think a better writer could have done with its premises, so perhaps I could try to become that better writer. Who knows? A deep-fried human pretzel might turn up in some future creation of mine.

Kirihito is easily the worst I have read from Tezuka. The comedian Stewart Lee once said of Jeremy Clarkson: “He’s either an idiot who actually believes all the badly-researched, lying, offensive shit that he says, or he’s a genius who’s worked out exactly the most accurate way to annoy me.” While I would never smear the venerable Tezuka-sensei as an idiot, a similar sentiment characterizes my relationship with Ode to Kirihito.

If you want a much better comic of human cruelty with literary ambitions and an epic, international scope, I would recommend Tezuka’s Message to Adolf. Adolf also suffers from its own missteps and gratuitous sexual violence, in particular an inexplicable out-of-character scene in which the otherwise upstanding hero Sohei Toge rapes a certain character. In my view, it adds nothing beyond some of that childish “I’m so dark and edgy” energy. However, in every other respect save the promotion of conspiracy theories, Message to Adolf, a more mature and confident gekiga work, is satisfying and coherent. Its artwork and storytelling remains the best I have seen from Tezuka so far. That is saying something. Though, to my mild embarrassment, I have yet to read Buddha, Phoenix, or Black Jack. Please give any of those a look over Ode to Kirihito.