Published 15 January 2021

The “mythos” of Cthulhu is better known, but the public domain weird horror character that more interests me is the King in Yellow. Cthulhu has been overexposed in pop culture, the haunting punch “The Call of Cthulhu” possesses, old-timey racism and purple prose notwithstanding, irrevocably dulled. The more obscure King in Yellow remains crispy, like lettuce. After seeing so many references, I wanted to learn what all the fuss was about firsthand.

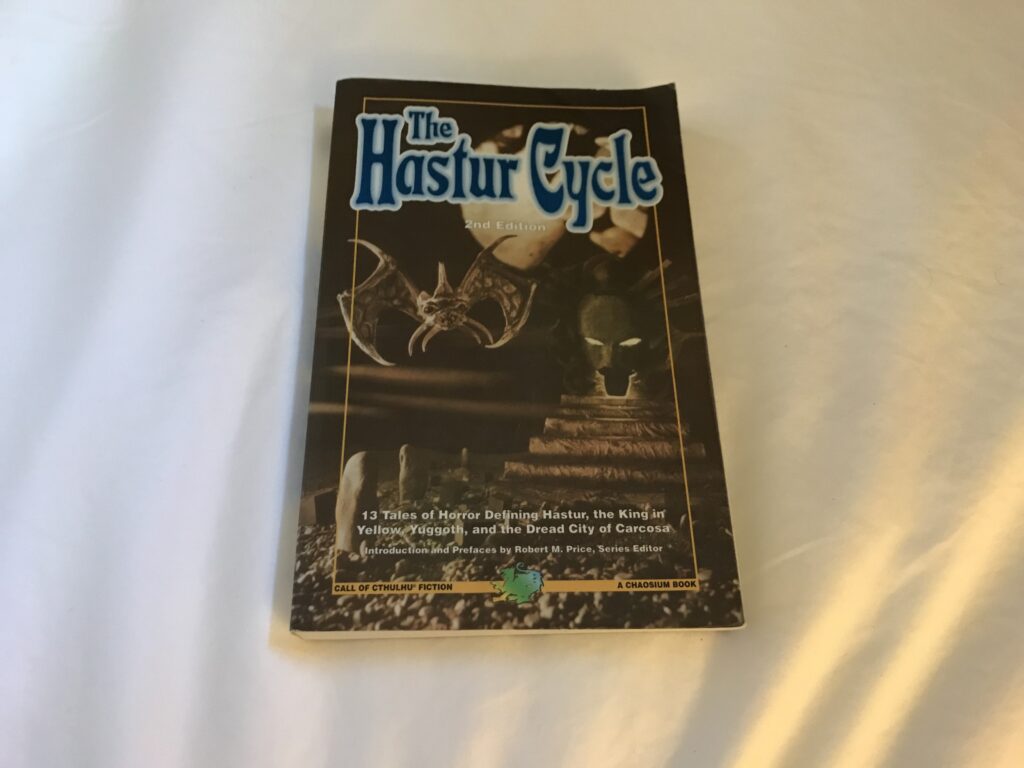

To this end, I procured an eldritch tome from a mysterious antique shop. Or, you know, ordered a used, beat-up paperback off the internet, whichever. The Hastur Cycle: Tales That Created and Defined Dread Hastur, the King in Yellow, Nighted Yuggoth, and Dire Carcosa, edited by Robert M. Price, was published by Chaosium in 1997 for players of their RPG Call of Cthulhu. Mine is the second edition. Oddly, the subtitle on the cover differs from the subtitle on the title page. I was excited to read a flimsy paperback for once, imagining the pulp pages that comprised the lurid pit from which “cosmic horror” emerged.

A complete list of the stories in this volume, in order:

“Haïta the Shepherd” by Ambrose Bierce (1893)

“An Inhabitant of Carcosa” by Ambrose Bierce (1886)

“The Repairer of Reputations” by Robert Chambers (1895)

“The Yellow Sign” by Robert Chambers (1895)

“The River of Night’s Dreaming” by Karl Edward Wagner (1981)

“More Light” by James Blish (1970)

“The Novel of the Black Seal” by Arthur Machen (1895)

“The Whisperer in Darkness” by H. P. Lovecraft (1931)

“Documents in the Case of Elizabeth Akeley” by Richard A. Lupoff (1982)

“The Mine on Yuggoth” by Ramsey Campbell (1964)

“Planetfall on Yuggoth” by James Wade (1973)

“The Return of Hastur” by August Derleth (1939)

“The Feaster from Afar” by Joseph Payne Brennan (1976)

“Tatters of the King” by Lin Carter (1965, 1989, 1993)

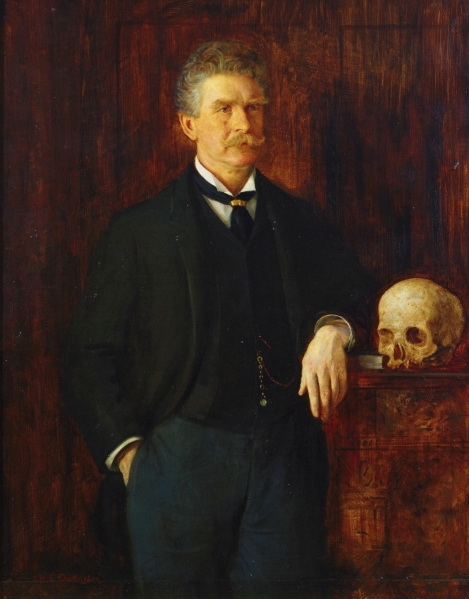

Ambrose Bierce, author of “Haïta the Shepherd” and “An Inhabitant of Carcosa,” was quite the character, sort of like his contemporary Mark Twain had Twain specialized in horror instead of satire. Bierce also wrote satire, though, and his haunting Civil War stories tend to combine elements of both. His prose style tends toward cold naturalism but becomes more poetical, or sappy, in the two horror stories included here.

Later writers depicted Hastur and Carcosa so differently from Bierce. Some of them may not have realized that Robert Chambers didn’t invent these names. In “Haïta the Shepherd,” Hastur is a benign woodland deity. The tragedy that befalls Haïta has nothing to do with the god he worships but rather the sorrow and disappointment of life. A cynical parable, “Haïta the Shepherd” tells the reader that happiness is rare, a mere flicker, never lasting. I like that when Haïta meets Happiness, though, the description includes this: “so sweet [was] her look that the hummingbirds thronged her eyes, thrusting their thirsty bills almost into them” (4).

Told from the perspective of Hoseib Alar Robardin, a traveler trying to find his way home, “An Inhabitant of Carcosa” does not depict Carcosa as a nightmarish alien city. On the contrary, Carcosa is the home to which the vaguely Arabian Hoseib wants to return. The horror here is that the deserted ruins he arrives in are Carcosa, an ancient city now long dead, that his home is lost forever and he himself is a ghost. This Carcosa is clearly on Earth. The narrator even thinks to mention “God,” not “Hastur” or some alien deity. The tale still has weird fantasy details, though, like stating the words were channeled through “the medium Bayrolles by the spirit Hoseib Alar Robardin.”

From these stories Robert Chambers lifted the names “Hastur” and “Carcosa” and nothing else. Today, Chambers is most famous for the bizarre horror story collection The King in Yellow, probably because of its influence on Lovecraft. Despite the title, only some of the stories in this collection actually involve the King in Yellow or the in-universe play also called The King in Yellow.

The book opens with an epigraph supposedly from the play itself:

“Along the shore the cloud waves break,

The twin suns sink behind the lake,

The shadows lengthen

In Carcosa.

Strange is the night where black stars rise,

And strange the moons circle through the skies,

But stranger still is

Lost Carcosa.

Songs that the Hyades shall sing,

Where flap the tatters of the King,

Must die unheard in

Dim Carcosa.

Songs of my soul, my voice is dead,

Die though, unsung, as tears unshed

Shall dry and die in

Lost Carcosa.

—Cassilda’s Song in The King in Yellow, Act 1, Scene 2” (11)

Though, in the third stanza, The Hastur Cycle printing is notably missing the word “in.” The black stars, two suns, a lake, and the Hyades create an eerie alien image that define every subsequent depiction of Carcosa in The Hastur Cycle. It is rare to encounter an extraterrestrial setting depicted as a decrepit, maybe medieval ruin. But that world would be more alien to us than a conventionally “space age” one.

Chambers’s “The Repairer of Reputations” is the most canonical story of all King in Yellow fiction. Since later writers have extrapolated almost every detail about of the King in Yellow mythos from this particular text, I will feature some long quotations. The narrator, Hildred Castaigne, describes it this way:

“During my convalescence I had bought and read for the first time, The King in Yellow. I remember after finishing the first act that it occurred to me that I had better stop. I started up and flung the book into the fireplace; the volume struck the barred grate and fell open on the hearth in the firelight. If I had not caught a glimpse of the opening words in the second act I should never have finished it, but as I stooped to pick it up, my eyes became riveted to the open page, and with a cry of terror, or perhaps it was of joy so poignant that I suffered in every nerve, I snatched the thing out of the coals and crept shaking to my bedroom, where I read it and reread it, and wept and laughed and trembled with a horror which at times assails me yet. This is the thing that troubles me, for I cannot forget Carcosa where black stars hang in the heavens; where the shadows of men’s thoughts lengthen in the afternoon, when the twin suns sink into the lake of Hali; and my mind will bear forever the memory of the Pallid Mask. I pray God will curse the writer, as the writer has cursed the world with this beautiful, stupendous creation, terrible in its simplicity, irresistible in its truth—a world which now trembles before the King in Yellow. When the French Government seized the translated copies which had just arrived in Paris, London, of course, became eager to read it. It is well known how the book spread like an infectious disease, from city to city, from continent to continent, barred out here, confiscated there, denounced by Press and pulpit, censured even by the most advanced of literary anarchists. No definite principles had been violated in those wicked pages, no doctrine promulgated, no convictions outraged. It could not be judged by any known standard, yet, although it was acknowledged that the supreme note of art had been struck in The King in Yellow, all felt that human nature could not bear the strain, nor thrive on words in which the essence of purest poison lurked. The very banality and innocence of the first act only allowed the blow to fall afterward with more awful effect” (14–15).

Later on, this passage adds a few more details to The King in Yellow, albeit from a delusional manuscript about how the King is going to subjugate the United States: “[Mr. Wilde] mentioned the establishment of the Dynasty in Carcosa, the lakes which connected Hastur, Aldebaran and the mystery of the Hyades. He spoke of Cassilda and Camilla, and sounded the cloudy depths of Demhe, and the Lake of Hali. ‘The scolloped tatters of the King in Yellow must hide Yhtill forever,’ he muttered, but I do not believe Vance heard him. Then by degrees he led Vance along the ramifications of the Imperial family, to Uoht and Thale, from Naotalba and Phantom of Truth, to Aldones, and then tossing aside his manuscript and notes, he began the wonderful story of the Last King” (32).

The only frequent feature of the King in Yellow not present in “The Repairer of Reputations” is the “Yellow Sign,” a mark that summons the Yellow King as an entity that exists outside the play. I should mention that “The Repairer of Reputations” is, for some reason, set in New York City in what was then the future year of 1920, when the administration of President Winthrop has made the United States a utopia by, among other things, “the exclusion of foreign-born Jews” and “the settlement of the new independent Negro state of Suanee” (11). Did I mention Chambers was also racist? In addition, Winthrop makes suicide legal and has suicide booths set up in every city for the purpose. Meanwhile, Tsarist Russia has conquered all of Europe. The titular “repairer of reputations” is Mr. Wilde, an aggressive dwarf with prosthetic ears and no fingers on his left hand. Wilde lives in a filthy apartment with a vicious cat that ends up killing him. Supposedly, this man runs an agency that will repair people’s reputations for a price, but he is in league with the King in Yellow, who, despite being a character in a play, is also somehow a real alien conqueror, possibly. Hildred and Wilde get entangled in a murder plot. Hildred himself, our only source of information about this world, is delusional, so it is unclear if anything he tells the reader about the world or The King in Yellow is true. Perhaps there is no President Winthrop.

The Yellow Sign appears, naturally, in Chambers’s story of the same title, a somewhat better tale about an artist who falls in love with his model. The piece of this story that still sticks with me is this line, spoken by a bloated corpse the King in Yellow has possessed: “Have you found the Yellow Sign? Have you found the Yellow Sign? Have you found the Yellow Sign?” I imagine the monster swaying back and forth as it recites these words. Very creepy. All of Chambers’s King in Yellow stories rely on the horror being bizarre. A ghost, werewolf, or vampire might follow certain tropey rules, but the reader never learns what is going on with this King in Yellow.

At risk of a tangent, “The Yellow Sign” does fall victim to that silly trope of the narrator having written the whole thing while dying. In this case, he wrote, by hand, fourteen printed pages’ worth of text. Apparently he scrawls out the story in the gap between the King in Yellow murdering Tessie and the police arriving, which, given that the neighbors contact the police as soon as they hear Tessie scream, can be no more than a few minutes. Though in the throes of despair, this dying man somehow does not introduce a hint of desperation or mention his situation until the last couple paragraphs. The narrator’s manuscript also features extensive quotations. Can you remember every word of a conversation you had yesterday? While under extreme stress? Thoughtfully, he even ends the story on a dash, rather than just stop writing mid-sentence as he dies. The goofy ending almost ruins the whole story. Perhaps, in Victorian times, people could write by hand much more quickly?

Most of the other stories in The Hastur Cycle blur together. “The River of Night’s Dreaming” starts strong, with a woman convict escaping a freak bus accident and fleeing into a ruined town, but devolves into weird lesbian BDSM sexual horror. In a Victorian house sense fallen to tremendous ruin, the characters begin to lose their original identities, coming to play, in real life, the roles of the cast of The King in Yellow and the tragic ending that implies, something like happens to Hildred Castaigne and Mr. Wilde. In such a shocking twist, the protagonist is schizophrenic. Also, a monster turns up whose giant penis has blood “oozing from its toothless maw” (82). This strikes me as belonging to the same category as the “spooky monster with bleeding eyes” trope, where it is disgusting and scary but not in a threatening way. If I saw a creature with a bleeding penis, my first thought is that the creature is gruesomely injured, not that it poses a threat to me.

Blish’s “More Light” is an attempt at actually writing the text of the play The King in Yellow. What a mistake! Blish knows it, too. The story quotes a letter Lovecraft wrote him. Price features the relevant section: “If anyone were to try to write the Necronomicon, it would disappoint all those who have shuddered at cryptic references to it” (84). But Blish did not heed the warning. His rendition of the play is underwhelming, despite a decent attempt. Only a rare genius, like Comte de Lautréamont, could write something fucked up enough, but that sort of person would rarely be interested in this kind of genre fiction. Though I appreciate the way “More Light” blends reality and fiction. The narrator is Blish himself, reading what is supposedly a manuscript of The King in Yellow that Chambers wrote but never published.

“You do not understand me. I will explain

it once and then no more. Hastur, you

acceded to, and wore, the Pallid Mask.

That is the price. Henceforth, all in Hastur

shall wear the Mask, and by this sign be known.

And war between the masked men and the naked

shall be perpetual and bloody, until I come

again… or fail to come.” – The King in Yellow, page 109

Blish writes his play in blank verse. He interprets Hastur as a city, rather than an entity or god or, as many other writers have done, the name of the King in Yellow.

Arthur Machen’s “The Novel of the Black Seal” might be the most interesting story in the book. Machen believed, if not in the literal truth of the monsters he depicts in his horror stories, then in the truth of an occult reality underneath ordinary human perception. This conviction lends his writing a power. “The Novel of the Black Seal” was originally part of The Three Impostors, a complex novel of interconnected horror stories first published in 1895. Told from the perspective of his secretary Lally, the story concerns Professor Gregg, an anthropologist who wants, as he puts it, “the renown of Columbus,” meaning he wishes to be a famous explorer as opposed to initiator of the transatlantic slave trade and possibly the worst genocide in human history. What does Gregg want to explore? The hidden civilization pointed to by the titular black seal, a four-thousand-year-old black limestone artifact inscribed with glyphs in an unknown language. Professor Gregg thinks he has figured out who made it.

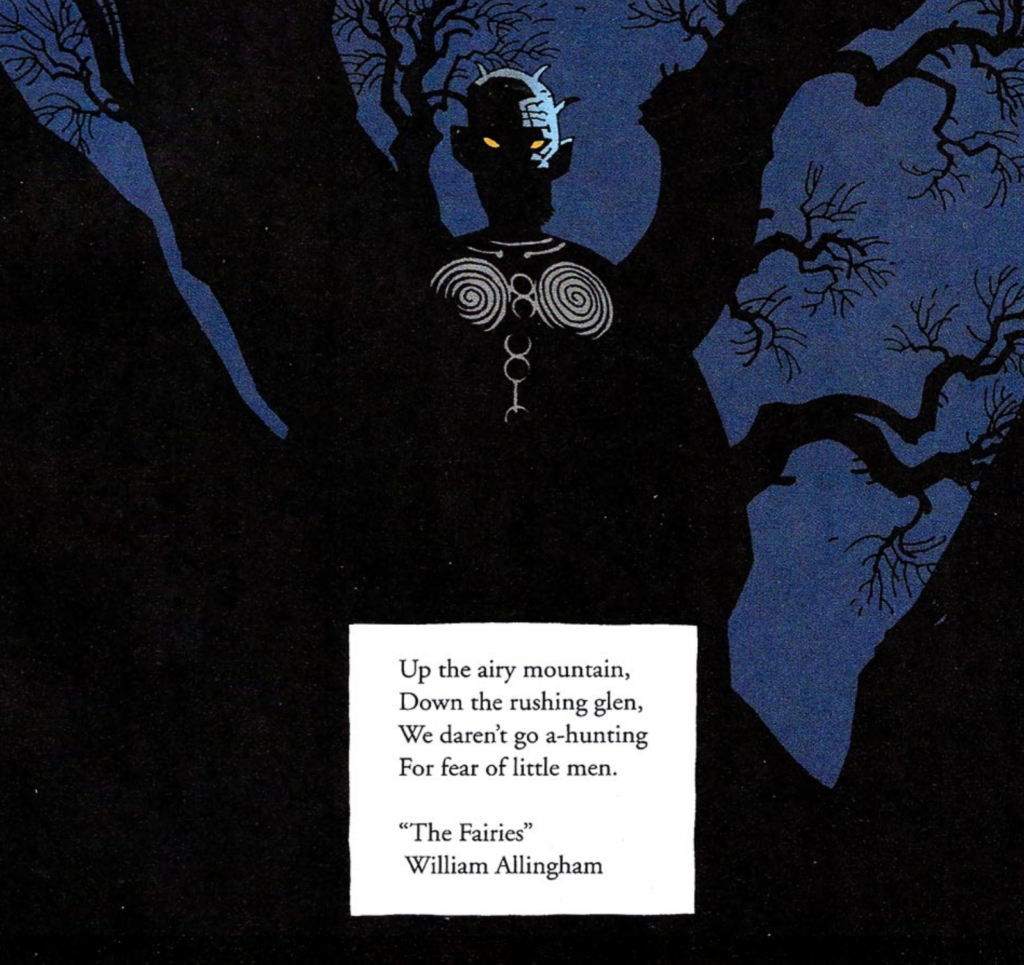

Gregg’s search ends up involving a boy with some kind of developmental disability who, it turns out, is a changeling. Only after Gregg’s disappearance does Lally, in the tradition of Victorian pulp fiction, find a document explains everything. The black seal is the work of fairies. Not Tinkerbell. The little people, the good folk, those unseen entities that, under one name or another, haunt almost all the world’s folklore. I am fascinated with fairies, and for a generally pretty grounded, scientific-type guy, am scared of them. Don’t go in the woods alone, or you might meet the good people and end up reduced to the primordial slime that is your earliest ancestor. Machen himself would write several more fairy-style horror stories, the most famous of which is probably “The White People.”

“The Novel of the Black Seal” has nothing to do with the King in Yellow except that “The Whisperer in Darkness” is its intertextual sequel. In the latter story, the narrator mentions Hastur, Hali, and the Yellow Sign, which do not figure in the actual plot. These name drops are the only narrative connection between the (original) Cthulhu mythos and the King in Yellow. Given Chambers’s vague, undefined alien monster and fictional text that drives characters mad, as well as the similar themes that recur throughout Machen’s writing, these names are not just “lore” but acknowledgments of Lovecraft’s inspirations.

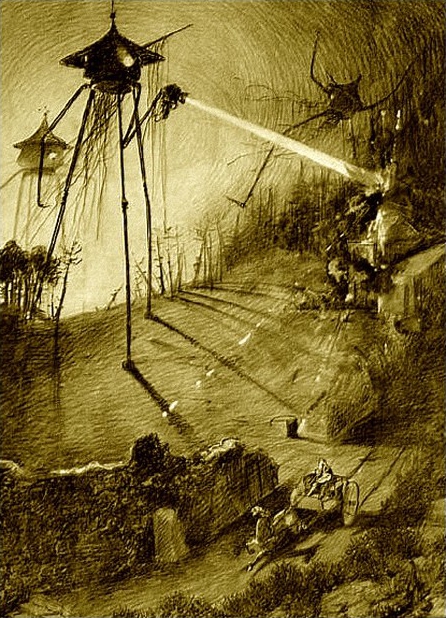

“The Whisperer in Darkness” concerns a literature professor named Wilmarth who gets in touch with Henry Akeley, a man at war with alien crab people from Pluto. Well, put that way, the story sounds goofy instead of gut-wrenching. It is all about execution. What links this to “The Novel of the Black Seal”? A piece of evidence that the aliens exist is a black seal Lovecraft lifted the artifact directly from that story, establishing a weird fiction continuity like Chambers did with Carcosa. In addition, the narrator Wilmarth directly alludes to “The Novel of the Black Seal”:

“It was of no use to demonstrate […] that the Vermont myths differed but little in essence from those universal legends of natural personification […which] gave to wild Wales and Ireland their dark hints of strange, small, and terrible hidden races of troglodytes and burrowers. […] Most of my foes, however, were merely romanticists who insisted on trying to transfer to real life the fantastic lore of lurking ‘little people’ made popular by the magnificent horror-fiction of Arthur Machen” (150–151).

Why did Lovecraft directly write Machen into the story? It would be much better if Professor Gregg existed in the same universe as Wilmarth, rather than existing as a fictional character. The black seal is real, after all! But this would also be impossible, or at least lead to a great deal of confusion, because in the full text of The Three Imposters (which is not included in The Hastur Cycle), Lally turns out to be an unreliable narrator who has probably made up the story about Professor Gregg and the fairies.

If you had asked me before I read The Hastur Cycle, I would have told you Lovecraft was a bad writer. A creative one, but on the level of prose style, sloppy, with forgettable, one-note characters who exist only as vessels for fantastical visions, racism, and nihilistic philosophy. Reading “The Whisperer in Darkness” alongside the rest of The Hastur Cycle, however, I realized I give Lovecraft too little credit. It stands head and shoulders above everything else in the book! As with Machen, the power in Lovecraft’s writing stems from conviction. Lovecraft did not believe that Cthulhu or, in this case, the Outer Ones existed in reality, but he did believe in the nihilistic philosophy (and frequently the racist anxieties) that the monsters represented.

The central conceit of “The Whisperer in Darkness” is that extraterrestrial life exists—not what the alien Outer Ones are up to, which is mining rare metal in rural Vermont, but simply that they are real. There is not much of a reveal beyond this. The twist ending is Wilmarth realizing he spoke with an Outer One. I do not believe this makes “The Whisperer in Darkness” bad. I mean only to remark on how an idea that audiences may have considered shocking enough to support a whole story in 1931 is, today, so banal that it would be the starting point of the tale.

“Documents in the Case of Elizabeth Akeley,” “The Mine on Yuggoth,” and “Planetfall on Yuggoth” are all sequels to “The Whisperer in Darkness.” At this point, the reader has firmly left the mythos of the King in Yellow and firmly entered into the mythos of Yuggoth, what the interdimensional aliens call Pluto in Lovecraft’s story.

“Documents in the Case of Elizabeth Akeley” is the best of these three. It hops from 1930 to 1979. Elizabeth Akeley is the granddaughter of Henry Akeley and head of the Spiritual Light Brotherhood, a Christian cult that, amazingly, has nothing to do with the Outer Ones, Hastur, or Cthulhu. Her grandfather, in a new body, returns from his journey through the cosmos. Then the former human and his alien friends coerce/trick Elizabeth and her boyfriend into having their brains removed so that Henry and his extraterrestrial lover can inhabit human bodies. A scary idea, to be sure, and a logical extension of the brain-removal technology Lovecraft introduced in his story. Strangely, this plot is mediated chiefly through an undercover FBI agent who has infiltrated the Spiritual Light Brotherhood. There are a lot of other weird details, like how one of the Akeley clan’s ancestors was named Beelzebub Akeley (206). I know people throw around a lot of Biblical names, but this one is a hair too far. Perhaps it suggests their lineage was cursed from the day they arrived in North America, but the goofiness undercuts the ominousness. Then again, the entire story is goofy.

“The Mine on Yuggoth” is forgettable and derivative. A man finds a portal to Yuggoth and, once there, sees one of those cosmic horror things that is so scary the author can’t even describe it. “Planetfall on Yuggoth,” though, is memorable in how bad it is. The author, Wade, extrapolates that if Yuggoth is Pluto and humans are exploring outer space (this was written after the first moon landing), then, like Wilmarth warns at the close of “The Whisperer in Darkness,” something terrible will happen if humans reach Pluto. When the astronaut Carnovsky lands on Pluto, he begins babbling “half-remembered quotations from the pulp writer who had fantasized so long ago about dark Yuggoth” (246). Wade repeats Lovecraft’s mistake of making the earlier story exist as a fictional short story in the universe of his fiction. What is the implication here? That Wilmarth was real and, for some reason, published his account of Akeley’s disappearance and warning to the world via a reclusive racist pulp horror writer? Did Wilmarth dictate to Lovecraft? Or is the idea that Wilmarth is the pulp writer? And why, on seeing Yuggoth, is Carnovsky quoting some random horror story he read once that does not even mean much to him?

The ending is laughable and highlights an issue I think blights a lot of Lovecraft-inspired fiction. Carnovsky cries, “My God! It can’t be! It’s a city! Great tiers of terraced towers built of black stone—rivers of pitch that flow under cyclopean bridges, a dark world of fungoid gardens and windowless cities—an unknown world of funguous life—forbidden Yuggoth! […] The Outer Ones, the Outer Ones! Living fungi, like great clumsy crabs with membranous wings and squirming knots of tentacles for heads!” (246). This is the last message Carnovsky transmits to Earth before, apparently, the Outer Ones kill him or perhaps remove his brain. When faced with alien life and then his own imminent death, this astronaut naturally starts screaming an imitation of Lovecraft’s campy prose, really piling on the adjectives. Faced with terror and awe, what the hell kind of person spontaneously exclaims “a dark world of fungoid gardens and windowless cities”?

I get the sense that Wade, and a lot of writers, assume that Lovecraft’s stories are scary, when they’re scary, because of his overblown style and use of words like “funguous” and “cyclopean.” Such authors (usually badly) imitate this surface-level material to indicate their story has entered “scary mode.” My advice is to use the style that comes naturally to you, not a forced imitation of somebody else’s.

Speaking of shallow fanservice for Lovecraft nerds, “The Return of Hastur” might be even worse because August Derleth had a few original ideas that get muddled in his determination to cram as many Lovecraft references in there as possible. Straight-up bad is less upsetting than something with glints of good in it that fails to deliver.

In the foreword to “The Return of Hastur,” Price mentions that Derleth sought feedback from Lovecraft’s friend Clark Ashton Smith. In response, Smith suggested, “For my taste, the tale would gain in unity and power if the interest were centered wholly about the mysterious and ‘unspeakable’ Hastur. Cthulhu and the sea-things of Innsmouth, though designed to afford an element and interest of conflict, impress me rather as a source of confusion” (248). I agree. As it is, the story is subpar Lovecraft fan fiction starring even shallower characters than Lovecraft favored. The narrator hears squishy sounds as Hastur and Cthulhu wrestle. But isn’t the takeaway of “The Call of Cthulhu” that, if Cthulhu escapes R’lyeh, and certainly if he got as far as New England, the world has ended? In this story, the narrator thwarts the Old Ones using explosives. At least we established that the Deep Ones have something to do with Hastur’s mischief. To quote YouTuber Dan Olson, there is no meaning, only lore.

“The Feaster from Afar” is the last complete piece in The Hastur Cycle. It is a competent horror story. Unlike Wade, Brennan does not get lost in extraneous lore. The smug novelist Sydney Madison goes on a retreat to an isolated hunting lodge in rural New England, where he begins feeling weird vibes and receives cryptic warnings from the locals. He suffers recurrent vivid nightmares of the Feaster from Afar, Hastur, pursuing him through a nighted wilderness. Inevitably, as a result of Madison’s arrogance and skepticism, something grizzly happens. Classic horror stuff.

However, Brennan falls yet again into one of same traps as Wade: he decides Lovecraft’s pulp fiction exists in-universe. “It’s suthin’ spoke about in the Cthulhu Mythos—yew heerd a that, I hope?” one of the country folks tells Madison in a rather silly funetik aksent (277). Of course, the foolish city slicker Madison is as contemptuous of Lovecraft as he is of the locals: “Madison had skimmed through part of [Lovecraft’s work] with disgust” (277). Outside of a comedy or a much more surreal and metatextual narrative (see In the Mouth of Madness), it is too silly to suggest that a pulp fiction author, obscure in his lifetime, was secretly writing true prophecies about real-life alien monsters.

The Hastur Cycle ends with some fragments by Lin Carter that include his own underwhelming edits to Blish’s underwhelming The King in Yellow script. Of all the writers in the collection, Carter is the first to reincorporate the sorcerer Hali whom Bierce mentions in “An Inhabitant of Carcosa.” Most others, following Chambers, instead use Hali as the name of the lake where Carcosa is situated. Bringing back Hali the person serves as a kind of bookend to…end the book.

In the introduction, Price suggests the reader consider The Hastur Cycle a literary genealogy. It is as the transmission and mutation of weird ideas over a century and not as narratives in of themselves that these stories are most interesting. The word cycle in the title, suggestive of real-world myths such as the Oedipus Cycle or Baal Cycle, implies a much tighter mythical narrative sequence than occurs. From Chambers onward, there is a dilution of meaning. More generously, I might say a change in meaning, but while that happens too, in this case I think there is a net loss. A spark of inspiration present in the earliest tales transforms into thoughtless imitation.

An inherent shortcoming of latter-day Cthulhu and Hastur mythos writings, it seems to me, is that their authors are playing with dead men’s ideas and not their own. Lovecraft’s circle mostly wrote about original concepts. Chambers seems to have lifted “Carcosa” and “Hastur” from Bierce to give a horror reader of the day a sense of a broader cosmos, of Bierce’s gloomy themes, but not the literal continuity of Bierce’s stories. Chambers did not feel the need to create some elaborate lore around the King in Yellow. His stories are scarier and more memorable for not explaining that the King in Yellow is Hastur, Cthulhu’s half-brother who can only use his powers when the Hyades are at the tenth meridian or whatever. Without the internet, readers would not have been able to Google “Carcosa,” but, perhaps remembering the Bierce story, might have felt like they heard of it before, lending the horror greater credibility. Lovecraft did not lift the Outer Ones from some earlier writer and, contrary to later canon-welding, was often not particularly interested continuity beyond what served his stories. His mythos is frequently inconsistent. Lovecraft was able to use his monsters to explore the themes he wanted to explore, where writers like Wade and Derleth, at least in their fiction anthologized here, write tales more akin to shallow fanservice for continuity nerds than a cohesive vision in their own right. Clearly I too am a Lovecraft nerd, but I am a good story nerd first and foremost. Something like At the Mountains of Madness might mention Cthulhu, but it serves the themes of transience, social decay, and extinction, and Lovecraft’s single most affecting story is “The Outsider,” which doesn’t involve the Cthulhu mythos at all.

Carter and Derleth seem to think that if they name-drop enough spooky Lovecraft monsters or make their creatures sufficiently wet and funguous their story is now scarier or deeper. Incidentally, when Lovecraftian writers are performing their rote namedrops, “Hastur” seems more frequent than “King in Yellow,” probably because “Hastur” fits in better with nonsense names like “Cthulhu” and “Shub-Niggurath.” Some writers seem to remember Lovecraft’s characters going mad but think it is because Cthulhu or the Yith are so big and ugly and not because of the ideas these beings represent. They seem to believe the use of weird names other authors invented is what makes a story good and not its style, themes, or characters. Wagner and Blish are the only later writers in this anthology who understand and attempt to play with the themes of the original King in Yellow stories instead of shuffling around “lore.” In his introduction to The Hastur Cycle, Price agrees in part, mentioning “Derleth’s characteristic flaw of cramming too much mythos data into a story, making it substitute for action and atmosphere” (xiv), though then defends the practice in this instance.

Price also introduces an insight I had not considered: “Did [The King in Yellow] supply incantations to call up Satan? Hardly; it did not need to stretch so far to find poison to destroy the souls of its readers. The play set forth the nullity of all human hopes […] As the sophisticates and avante-garde [sic] read the book, they became infected with its jaded nihilism. […] The King is swathed in yellow for the same reason Oscar Wilde wrote for The Yellow Book. It was the banner of Decadence in the Yellow Nineties” (ix).

Interpreting the fictional King in Yellow play as a book of nihilistic debauchery, apocalyptically so, causes the vague details to crystalize. This is why the characters in Chambers’s King in Yellow tales are urban aesthetes, artists, madmen. Chambers was responding to and participating in the Decadent movement of the 1890s, European art about demons and violence and sexual and social perversity. For a minor example, Félicien Rops made a watercolor painting of a six-breasted sow-woman, nude except for jewelry, bent over, gripping the branch of a dead tree, inserting her phallic tail into her vagina. Now that is what I call decadent! In The Hastur Cycle, Wagner comes closest. Such decadent art, full of sex and violence and demons, may have offended the conservative Robert Chambers enough to inspire his nightmarish stories.

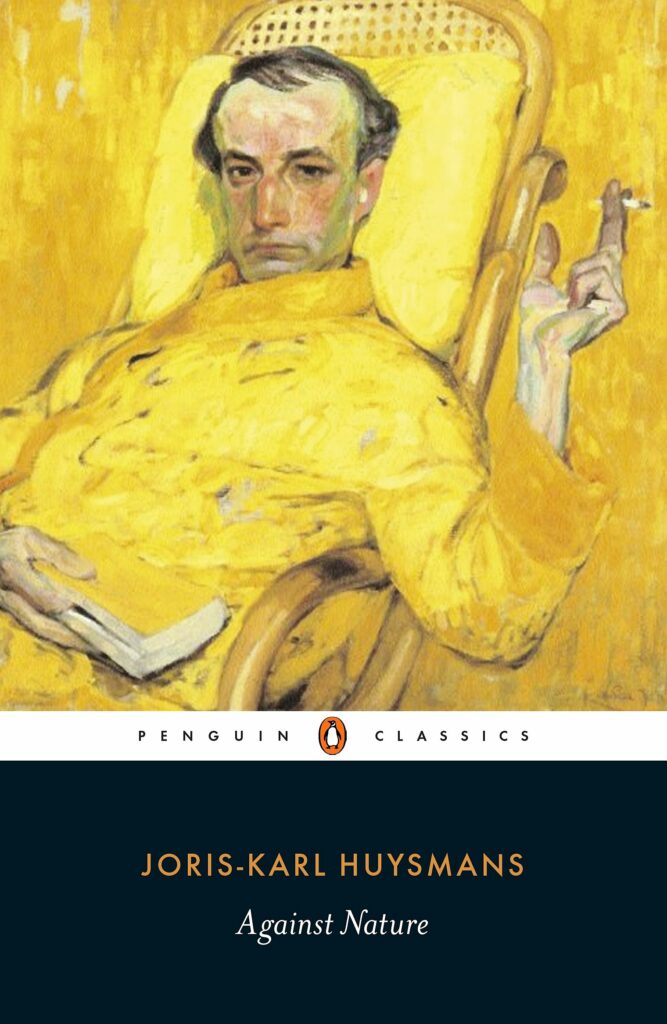

The depravity of Les Chants de Maldoror, a real-life decadent book of the day, is more convincing as The King in Yellow than what Blish and Carter put out. This could be the reason Chambers named his scheming, corrupting madman Wilde. Oscar Wilde was a prominent decadent in the Anglophone press, notorious for his homosexuality, which eventually led to his exile from Britain. Is The King in Yellow the corrupting book that Henry Wotton gave Dorian Gray? The Picture of Dorian Gray describes this volume as “a book bound in yellow paper,” one of many steps that lead Dorian to becoming a callous, cruel, libertine drug-user indifferent to the suffering he leaves in his wake (plus he is an extremely pretentious misogynist). Although Oscar Wilde gives the yellow book a fictional title, he may have been alluding to Against Nature, an 1884 novel by Joris-Karl Huysmans. It involves a neurasthenic nobleman, Jean des Esseintes, who leads an extravagant, wasteful life of sensuality. Ennui, perversity, nihilism, casual cruelty, society dissolving under the boredom and indifference of dying lineages whose greed and incompetence finally imploded into World War I: is this the real King in Yellow? Or is the King in Yellow a boogey man for people paranoid over disdain for traditional morality among artists and urbanites? Perhaps the breakdown of the original meaning over time mirrors the dissolving influence of this more abstract, entropic “king whom emperors have served.” It is no coincidence that the 2004 Penguin Classics printing of Against Nature takes, for its cover, a man in a yellow room, on a yellow chair, with a yellow book, all in yellow.