Published 13 March 2021

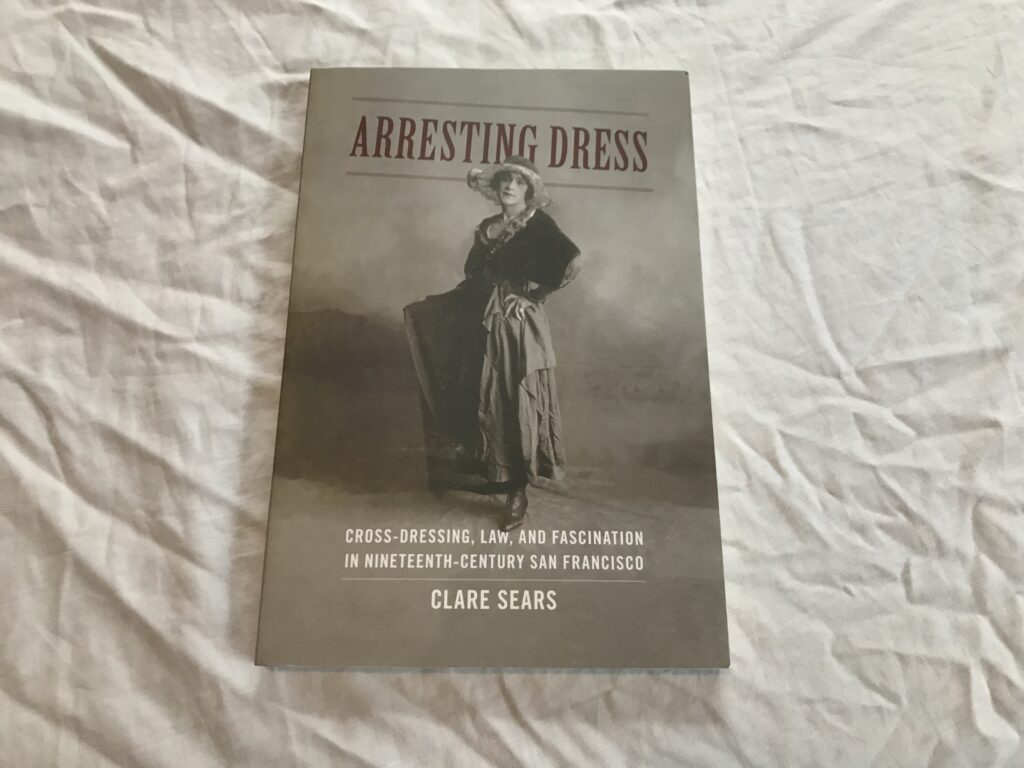

Arresting Dress, written by Clare Sears and published by Duke University Press, concerns crossdressing in nineteenth-century San Francisco and its relationship to the formation of policing, race, and respectability. Part of a series called Perverse Modernities, the book, at only one-hundred forty-seven pages ignoring the extensive bibliography, is not a long read. The subject matter, touching on extreme racism among other things, might be too unpleasant for some. The title is a pun, and that won my sympathy before I even opened the book. I learned quite a lot and will share some of that information here. In particular, I remember the story of Milton Matson.

Before 1863, crossdressing seems to have been comparatively normalized in San Francisco, at least under certain conditions. Because the city ballooned from the gold rush influx of predominantly male migrants, a significant gender imbalance emerged in the mid-nineteenth century (24). In 1852, for instance, women constituted only fifteen percent of the population, and earlier there had been even fewer (27). Because of the lopsided gender ratio, men would dress in women’s clothing or otherwise assume women’s roles in dances (30–31). “The predominately male, racially segregated gold mining camps, for example, were home not only to hard labor, heavy drinking, disease, and violence but also to cross-dressing recreations, as European American miners used items of clothing to gender the homosocial spaces of their men-only dances” (29). Two men can’t dance together, but if one of them pretends to be a “woman,” then it’s fine! And definitely, I should think, fun. Gay in more ways than one. These crossdressing parties would remain a point of proud local lore even after the city banned crossdressing. By necessity, people bent received gender norms in other contexts too. Sears quotes “one of the region’s few female migrants” Eliza Farnham: “it is no more extraordinary for a woman to plough, dig and hoe with her hands . . . than for men to do all their household labor for months” (33). As though to parallel the blurring borders of gendered labor, in San Francisco, women wearing bloomers or trousers became common, and notably women sex workers wore men’s clothing to signal their availability (38, 42). What law there was largely tolerated these practices (44).

I do not mean to depict this time in rosy terms. The invaders perpetuated horrible violence against Native American nations in nineteenth-century California. Shootouts and other forms of “frontier justice” were not uncommon (54). Widespread gender-bending activities did not necessarily challenge gender traditions, either. For example, Sears understands men crossdressing for dances as, ironically, reinforcing a gender binary through simulation (31–32). This practice also helped create the racial boundaries that would define genocidal settler-colonialism in the region, as racists often claimed people of color lacked gender differentiation as part of their supposed inferiority. The white supremacists of the day inextricably linked their racist pseudoscience with what would now be called queerphobia. Contrary to the fifteen percent statistic I mentioned earlier, there were, in fact, plenty of women already in the San Francisco area, but these women were Indigenous and Hispanic. The European American miners preferred white men dressed as women to actual women who were not white. White San Franciscans often openly celebrated white prostitutes. “One Frenchman brings twenty, all, they say, beautiful!” one paper praised another (white) pimp sailing into town (44). Simultaneously, the press condemned women in ethnic minorities (Chinese, Black, Hispanic) as “whores” even when they were not sex workers of any kind (44–45).

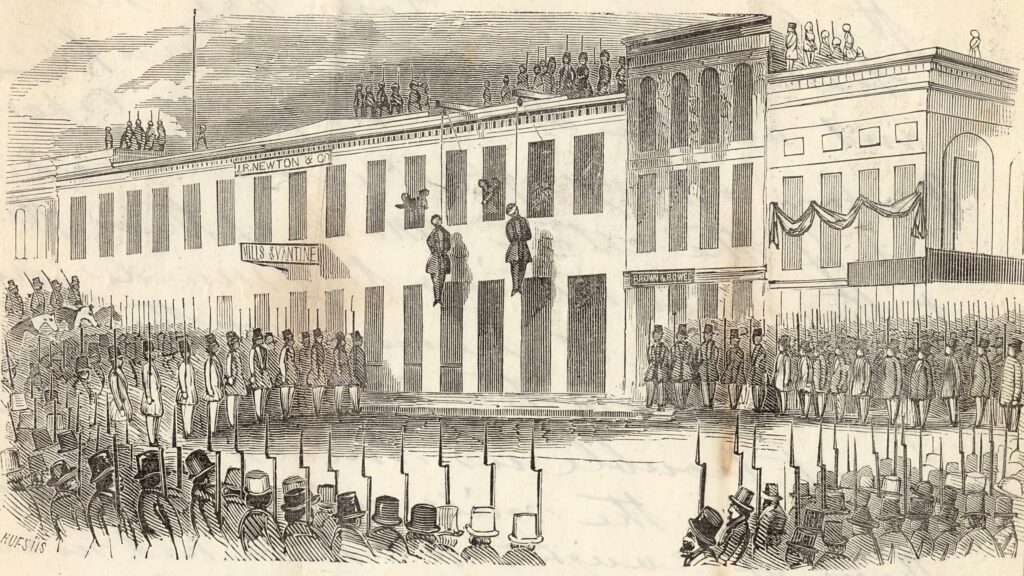

Then came the 1856 Vigilance Committee. In May of the year they were named for, these bourgeois Protestant vigilantes lynched Charles Cora and James Casey and seized control of San Francisco through armed insurrection. Cora was a gambler who went to prison after killing William Richardson, a bourgeois man who attacked Cora for sitting near him at a theater. Casey was a member of the Bulletin newspaper Board of Supervisors who shot one of the writers, James King, for supporting the antivice cause. After one of the rebels’ political prisoners died, the governor of California attempted to raise the army against the Vigilantes but failed utterly (52–55).

The Vigilantes went on to hold power through their “People’s Party” for some twenty years. A major part of their project was the manufacture of what Sears calls “a particular vision of normative gender as the foundation of social order” (56). This “particular vision” was, of course, the binary, restrictive gender practices of middle-class Euro-Americans, a demographic emerging in San Francisco in the 1850s as gold rush immigration ended (46–48). By legislating morality, the Vigilantes aimed to “purify” San Francisco into a “respectable” city through the generous application of the only solutions powerful Americans seem capable of imagining for social ills: police and prisons. In addition to quashing cuss words and public drunkenness, the morality laws were meant to stop the blending and crossing of gender boundaries that had become standard practice in the city (60). Vigilantes wielded crossdressing caricatures to mock their rivals, mainly the Law and Order Party, in political cartoons (58). Those Law and Order sissies aren’t real manly men! Gender nonconformity was stigmatized, shifting, in San Franciscan discourse, from part of everyday life to ludicrous deviancy.

Supporters framed the Vigilantes’ radicalism as necessary to protect respectable “ladies” and “purify” San Fransisco. Using genocidal “infestation” rhetoric to refer to the largely Chinese and Hispanic underclasses, they branded the city a modern-day Sodom and Gomorrah (57). “Reworking the boundaries of acceptable womanhood, the ladies of Vigilante discourse denounced ‘unsexed’ prostitutes who were unworthy of the ‘name of woman’ and also ‘repugnant’ women’s rights activists, who were ‘ambitious of being pigmy men.’ […] Here, as the historian Mary Ryan explains, the respectable middle-class family could take root once ‘the dangerous female was banished from the pantheon of true womanhood’ ” (57). Reading history can be enraging.

Sears quotes from one 1855 report: “A virtuous woman cannot walk the streets without . . . being jostled against by harlots” (50). Aside from classist undertones (though, in this case, the “harlots” might have literally been prostitutes), the statement reflects emergent middle-class gender norms, a view of women as delicate and in need of protection. The middle-class women were not powerless, however, and many wholeheartedly supported the Vigilantes. During the Gold Rash days, in contrast, women were understood to be sufficiently capable of masculinity, or perhaps vice-versa, that a daguerreotype of John Colton, a man, could circulate as an image of a woman (37). Although one Sophia Sherwood, apparently a prostitute, was arrested for crossdressing in 1857, it was not until 1863 that morality laws officially prohibited crossdressing as part of the antivice crusade (41–42), enabling police to crack down on both public prostitution and gender practices that went against the “particular vision” of the ruling class. It is impossible to determine how many crossdressers remained undetected. The only such individuals we know about are those who were caught, and the arrest record suggests gender nonconformity by no means ever stopped. But, over the next decades, criminalization drastically reduced open crossdressing (75–76).

Sears emphasizes that the crossdressing laws were not a quirk of the project of defining normative middle-class values but part of an interconnected web of policing and segregating people by race and disability. “[T]hese laws created urban zones where problem bodies could be contained, primarily the racialized vice districts of Chinatown and the Barbary Coast. Consequently they [the morality laws] affected not only the movements of problem bodies but also the sociospatial order of the city, operating as early technologies of zoning that drew a series of boundaries between public and private, visible and concealed, and respectable and vice districts” (73). I hate how academics write about “bodies,” as in, “dictated the types of bodies that could move freely” on this same page. Bodies are trendy in academia these days, though I will take scholars using the word “body” in silly ways any day over morality laws legislating whose body is acceptable to be seen in public. That is the kind of poisonous thinking that produced freak shows, as Sears focuses on elsewhere in the book.

The police (gasp!) did not enforce crossdressing laws equally for every group. For example, the Mexican Geraldine Portica was arrested for crossdressing in 1917. Today, we would probably call Portica a transgender woman. She had lived as a girl for almost her entire life. It is her striking, or I might say arresting, photograph that the publisher chose for the cover of Arresting Dress. While the pose and sardonic expression made me assume this picture came from some photoshoot, it is in fact the work of a police photographer fascinated by the appearance of someone whom the cops considered a boy dressed as a girl (136–137). That explains Portica’s sardonic expression. What was she thinking at that moment? As punishment, Portica was deported to Mexico. Sears speculates what specific charge they used to justify deportation, perhaps “moral turpitude,” a crime that does not sound like it would exist in any just system. In contrast, in 1903, San Francisco police arrested two wealthy European American women, Mrs. Dubia and Mrs. Dessar, for wearing men’s clothing on a slumming tour. Instead of being brought to a prison cell as per standard procedure, they were allowed to immediately plead their case to the chief of police. After they produced evidence that they were staying at an expensive hotel, he let these respectable wives and mothers off with a lecture (65, 115). Clearly, Dubia and Dessar received preferential treatment. However, their story suggests that crossdressing, at least for women, was not so beyond the pale that wealthy tourists were not open to the idea. Dubia spoke of it to a newspaper in casual terms: “[wearing men’s clothes slumming] would be better in every way, [for] climbing up and down ladders, and that sort of thing” (115).

This leads to another phenomenon that emerged in the mid- to late nineteenth century: newspaper reporting on crossdressing. Paradoxically, by encouraging news coverage, the anti-crossdressing laws encouraged people to seek out and publicly display crossdressers (86). San Francisco journalists showed biases of their own, giving sensationalized reports on numerous white crossdressing crimes but ignoring Chinese and Hispanic crossdressers (99). The press treated most crossdressing cases as simply one crime among many, giving them no more attention than an arrest for, say, drunkenness (91). Sears gives an example of a non-white crossdresser receiving press coverage in Oakland, near San Francisco. The crossdresser was one So Git, who was framed, unlike white crossdressers, not as a case of “individual pathology” (94) but as part of a Chinese criminal conspiracy, likely a fantasy born out of racist “Yellow Peril” fearmongering and sensationalist reporting (95). White crossdressers were lone deviants, but a Chinese crossdresser represented the deviancy of all Chinese gender expression. But in So Git’s case reporters “virtually [fawned]” over their feminine apparel (95), the same as the press did in reports on white crossdressers like Edward Livernash or Mamie Baldwin (91–93), hooking readers in with salacious details. This scrutiny of their gender displays was part of these people’s punishments. Acknowledging the public humiliation, the judge in Mamie Baldwin’s case gave a fine of only $5, saying, “You have had your picture in the paper and all that sort of thing” (92). This reporting that showcased gender variation supported the same agenda as the morality laws that hid gender variation in jails. Both stigmatized everything outside that particular vision of gender, playing up those deemed crossdressers as “queer freaks” (91).

One “queer freak” being displayed appears in the story of my favorite “character” in the book, the colorful Milton Matson. If only he had written a memoir. Today we know him solely through sensationalist press reportage. In January 1895, Matson was arrested “in the room of his fiancée, Ellen Fairweather, on charges of obtaining money under false pretenses” (103). Two weeks later, the jail discovered that Matson was physically female. Matson is another example of someone who, today, would be called transgender. Apparently the false pretenses that led to his arrest involved trying to cash checks written to his feminine birth name. As a result, Matson walked free. Reporters recorded him defying the police: “I’d like to see anyone arrest me for wearing men’s clothes” (104).

The press ran numerous stories on Matson, depicting him as a swindler who had tricked Ellen Fairweather into believing he was a man. I, for one, doubt that Fairweather had not seen her fiancé’s body. In interviews, Matson criticized the press and spoke for himself, often with humor. “I’m beginning to think it pays to be notorious. It certainly does not seem to be a detriment to people in America” (104). He deemed it “outrageous . . . that a man cannot have any peace, but must be badgered to death by reporters.” “Yes, I like the ladies and in my earlier days was quite a beau. I was a good dancer and I guess I pretty thoroughly understood all about the female weaknesses. I have been made a confidante by the fair ones more than once and have had some interesting experiences. It was lots of fun carrying on flirtations with the ladies and a real joy to make love to them” (104–105). In need of money, Matson took a job at a San Francisco freak show as “The Bogus Man.” Apparently this involved sitting around and talking to visitors, whom I can only imagine were not too respectful despite his wit. Matson’s popularity led numerous other local freak shows to feature crossdressers of their own.

Despite the public attention, police did not arrest Matson again until 1903 (74). At police court, Matson pleaded for transgender recognition, though did not use that term, whose predecessor “transsexual” Magnus Hirschfeld would not coin for another twenty years. “Matson had lived as a man for several decades, and he called for the law to recognize that gender identity could diverge from anatomy. Matson took the stand in court to insist that he was a man, demanding that the state recognize his manhood, even as the police insisted that ‘the prisoner was a woman.’ […] Matson was sentenced to sixty days in the women’s jail” (146).

Out of interest, I sought out the specific columns in the 27 and 28 November 1903 editions of the San Francisco Call from which Sears pulls the information about Matson’s appearance in police court. They are, predictably, bigoted. The 27th November edition, “SUPPOSED MAN PROVES WOMAN,” elaborates that Matson was again charged for obtaining money under false pretenses. This time the crime involved begging for money to support the family of a fictional dying man named James Bryant. The detective uses only masculine pronouns when talking about Matson yet closes with: “I am satisfied that Matson is a woman, but prefers to wear men’s attire.” Because Matson is so obviously a man, even the detective cannot help but acknowledge him as such.

This column includes a more extended Matson quote irrelevant to the case but interesting for the biographical details. However, in analyzing these and every other quotation from Matson, it must be kept in mind that the journalist might have invented Matson’s speech to fill up space. This happened unfortunately often in those days. Also, if Matson was a swindler, he might not have been entirely honest. Or both. Matson is quoted: “I have been constantly in masculine garb for sixteen years […] and I never was discovered or even in danger of being discovered before. It was my mother’s desire that I should assume this attire. I was a twin, the other child being male. When I was 26 my twin brother died and at my mother’s request I donned male attire. For twelve years I lived in New South Wales. There I was managing a hotel and conducting an agency. All this time I was in male attire. For a year and a half I conducted a summer resort at Ben Lomond.” A trans man, in the nineteenth century, went undetected for over a decade and successfully ran multiple businesses. It is interesting to speculate why, having lived as a woman for twenty-six years, Matson so readily took to men’s clothing. Had Matson always wanted to live as a man, or did he enjoy escaping repressive societal expectations of womanhood? Or, again, both?

In the 28th November edition, Matson receives only four paragraphs, wedged between other brief write-ups in a section titled “Interesting Gossip of the Police Court.” The story following Matson’s, for example, involves two Black men who got into a knife fight. Their testimony is written with condescending phonetic spellings of their AAE speech. The judge let them off. Of Matson, the paper offers no detail not found in Sears but says simply: “She [Matson] did not droop her head and blush, nor did her high treble falter as she brazenly told the court she was a man.”

However, crossdressing law in San Francisco not only policed gender norms but drew attention to the possibility of their violation. While the press, government, and entertainers like those who ran the freak show that hired Matson framed crossdressing as insane, laughable, or dangerous, it is very possible that not everyone in the large audiences thus exposed to non-normative gender displays bought into such negative perspectives. Some people may have visited Matson at the freak show not to gawk but to speak to him about his experience. Sears takes care to express this idea: “To be clear, there is scant evidence of such responses, . . . [but] [n]eglecting the possibility owing to insufficient evidence . . . may be more problematic than raising it unsupported, as it replicates the structure of the archive” where such voices have been suppressed (119). Despite the violence the law inflicted on him, Matson did articulate to the judge and the newspapers a case for his gender identity.

In this manner, Matson’s arrest and press coverage, like some others’, “facilitated [non-normative genders’] public articulation and politicization” (146), something then new in United States history. Whether or not Matson was a swindler, today we tend to see “brazen” gender nonconformists like him, like Geraldine Portica and Mamie Baldwin, as the heroes of their stories, heroes, in many cases, for existing at all in cultures so bigoted. And we tend to see those vicious institutions, journalists, and cops who persecuted, misgendered, and jeered at such individuals for daring to live their lives as a sobering reminder of how ugly the past so often was. However, the persistence of people like Portica and Matson and the inability of Vigilante-minded authorities to ever eliminate practices that fell outside their smothering “particular vision” reminds us (or me, anyway) that the past can also offer hope and a sense of where we are today.