While my AC was out during the hottest days of the year (so far), I escaped from sweaty reality into one of the video games of my luxuriant Steam backlog: Jet Set Radio. Weeks before, I had played about an hour of it. Then, frustrated, I quit. This time, however, Jet Set Radio cast its spell over me for hours at a time, deep into the night, until I saw Goji plummet to his death multiple times, somehow.

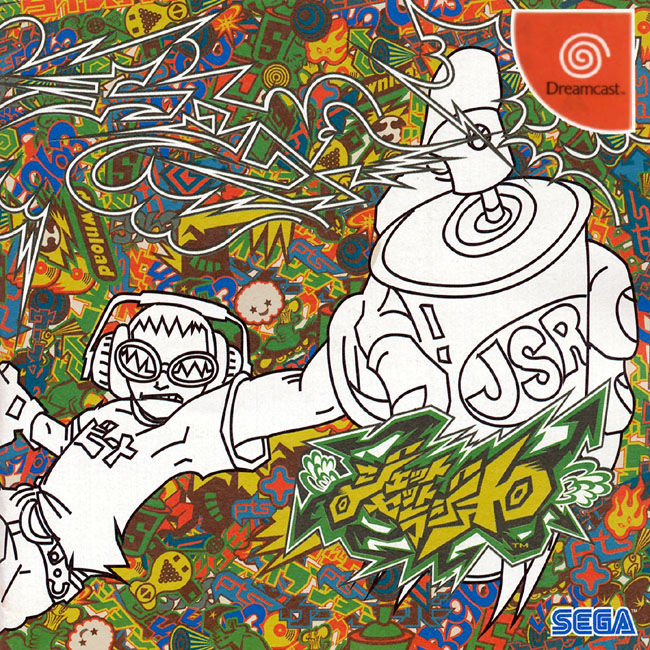

The 2000 Dreamcast original, purportedly the first video game that used cel-shaded polygons to emulate a “cartoon” look, ranked among my “video game legends” for years. These are video games with an aura of historical importance and, because of obsolescence and inaccessibility, mystery too. I own a Dreamcast but never thought to seek out a physical copy because Sega released Jet Set Radio HD in 2012. Here, “HD” does not mean upscaled textures or higher polygon counts but only a higher resolution appropriate for today’s screens. As a result, I could appreciate the pixelated graffiti and chunky character models in their awkward 2000 glory.

In Jet Set Radio, originally released in the US as Jet Grind Radio for copyright reasons, the player controls rollerblading delinquents called “Rudies” in different urban levels based off parts of Tokyo. The opening narration identifies the setting as Tokyo-to but immediately adds that they just call the place Tokyo, making me wonder why the writer made this decision. The cold open is a tutorial where the player forms a gang called the GGs, initially consisting only of Beat, Gum, Tab, and their dog Potts. Over the course of the story mode, the player can recruit seven additional Rudies to the GGs, each with their own different stats affecting speed, inertia, graffiti skill, and paint maximum. There are also six (I think?) hidden characters, including a cybernetically modified Potts. The player will revisit the same environments multiple times to complete different goals, fulfilling five different mission types. The most common involves spray-painting graffiti on a certain number of preset targets within a time limit. Red arrows mark required targets and green optional ones. To fill the paint meter, the player collects spray cans alluringly hovering around the level. Yellow cans correspond to one can of paint, but the rarer blue cans add five to the Rudie’s supply. Red cans instead refill the HP meter, which might imply the Rudie is drinking paint? Perhaps the red spray cans are full of a futuristic health drink since Jet Set Radio, judging from the reboot Jet Set Radio Future, is theoretically set around 2024.

Some targets you can tag with a single press of the trigger, but others force the player to stop dead in their tracks and move the analog stick as directed by on-screen prompts that imitate the Rudie’s dance-like movements, as though graffiti requires fluid grace like a calligrapher’s brush. Quick-time events generally ruin any video game unlucky enough to include them (looking at you, Bayonetta), but Jet Set Radio pulls it off. In the story missions, squads of enemies complicate this process, initially the fanatical Onishima’s cops and later the Golden Rhino yakuza rushing in with bullets, tear gas, and fire to stop the Rudie with ludicrously overwhelming force. If the cops will hunt you with earthbound units like dogs or SWAT units, a good strategy is to begin on the street-level graffiti, since otherwise you will have to hit these targets with a mob of goons on your tail. The time limit and increasing enemy presence add strategy and target prioritization to what at a glance looks like a casual skating game. There is no full-proof method to tagging quick-time event walls while the cops are on your tail, but completing a row of analog stick swipes tends to warp the Rudie to a different part of the wall for the next animation, which can be enough to dodge an enemy tackle.

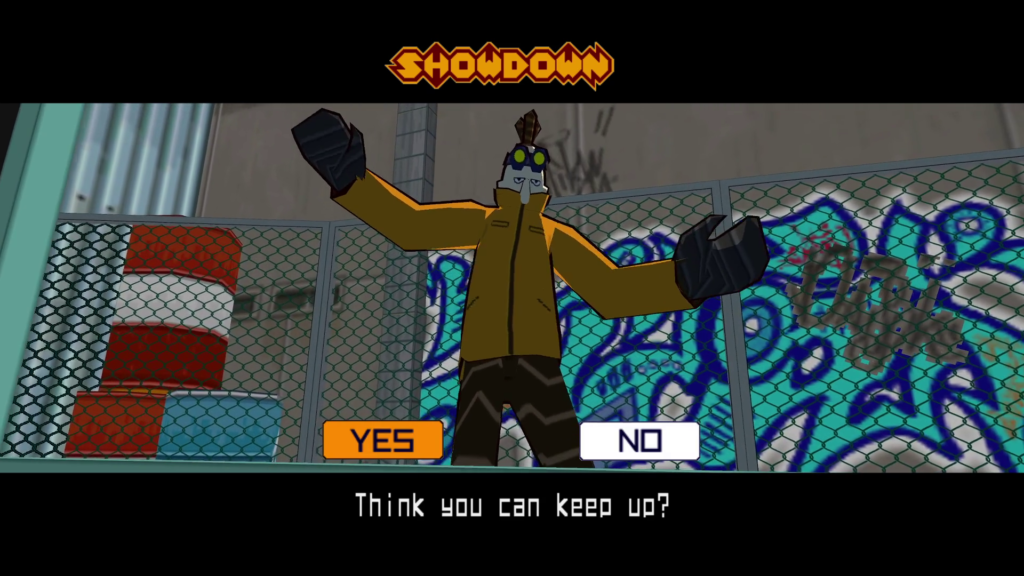

The second mission type, the most common challenge the player must complete to recruit someone to the GGs, is performing a series of stunts. The player watches the prospective GG member run through some moves and then must copy them. The third mission type has the player race against a computer-controlled Rudie to tag a particular spot. These missions are a real pain, since the sprawling urban environments offer no hint about where to go. To stand a chance, you more or less have to follow your opponent and memorize the route. I recommend always choosing Garam for these levels, as his high speed should leave opponents in the dust, though you need skill to match that speed. The fourth mission type is tagging the backs of rival characters, resulting in lengthy chases. The fifth is just performing stunts to rank up as many points as possible. To reach the ending, the player never has to complete this type of level.

The simple controls involve only the analog sticks, the jump button, and the right trigger. This is almost too simple—the right trigger both snaps the camera in front of the player character and initiates tagging, which can be extremely disorienting in the chase missions. Belying the basic control scheme, Jet Set Radio is always unintuitive. The level design hews closer to real cities than conventional levels, often meandering and unclear with no signposting. In particular, the Shibuya-cho playground level seems to start the player facing the opposite direction they probably want to go. Early on, despite the small surface area, I found myself constantly consulting the map to figure out where I could possibly go. After I stuck with Jet Set Radio for a whole playthrough, I became so accustomed to the controls and the map layouts that I could breeze through the largest stages in a constant state of flow. Whether a “good” video game should be more accessible from the get-go or demand practice and patience I leave for others to ponder.

I am not the only one the janky design put off. Checking the global stats for Steam achievements, 87.4% have “Feel the Beat,” meaning they started Jet Set Radio, but only 59.6% have “We got us a crew,” meaning they reached the first level. What is effectively a tutorial (ironically, I didn’t complete the actual tutorial) loses a little under 30% of players. In an even more alarming drop-off, only 11.7% of players completed Chapter 1. In a review on Polygon, Arthur Gies is harsh: “Squirrely controls, camera catastrophes, and nonsensical level design make Jet Set Radio HD a better memory than a game.” I agree about the camera, but the controls are not “squirrely.” Gies is thinking of the character physics. Inertia is strong with the Rudies: slow to build up speed and slow to lose it, missing a jump by a few feet or plummeting off a ledge because you couldn’t turn around in time, haunt the whole game. On Gameinformer, Matt Helgeson better diagnosed the problem: “Your skater controls like a tank on ice skates. The lack of fine control is exacerbated by camera problems and the barely controlled chaos of the rampaging cops and urban traffic.” The madcap energy that sees the characters dancing also sees a world of such antagonistic madness that getting hit by a car can involuntarily carry you to the exit of a level! Yes, for some reason, every level has a road that will automatically return the player to the main menu, AKA the garage. When stopping your Rudie is tough, particularly if you have landed on the hood of a speeding car, riddling levels with automatic exits identical to the streets you can go down is plain mean.

Back in 2000, critics adored Jet Set Radio. DC-UK wrote: “A kind of cross between Crazy Taxi and Tony Hawk’s but better than both of them, Jet Set Radio combines the ‘speeding through bustling cities’ action of Taxi with the ‘use stunts to move around the interactive scenery’ fun offered by Hawk’s. And then it adds a garish tag of graffiti art and some bullet-dodging cop chases for good measure.” The writer goes on to praise the same sprawling, complex levels later critics derided, calls Jet Set Radio “a triumph,” and claims anybody who finds faults in it is “a misery guts.” In 2000, Jet Set Radio won “Best Console Game” at the Game Critics Awards and “Excellence in Visual Arts” at the 1st Annual Game Developer Choice Awards. The novelty of a cel-shaded world went a long way in winning favor, especially in the graphics-obsessed culture that dominated video games even more in 2000 than in 2021. The cartoon style was a welcome antidote to the almost pathological fixation on lackluster realism. I think the dissonance between critics in 2000 and 2012 also speaks to an underlying flaw in the video games industry, which never seems to remember its history beyond maybe one year and assumes that current popular standards for “good design” are the one possible standard for how video games should be. People talk about “aging poorly.” This is vapid, as Jet Set Radio didn’t age. Wine ages, physically changing. But Jet Set Radio is the same as in 2000. It is everything else that changed.

Unlike Gies or apparently over 90% of players, I persevered to the ending multiple times, achieving enough skill to blast through the levels with the exhilarating, graceful speed and thrill the premise of Jet Set Radio promises, but which the difficulty curve prevents. I was also bewildered to discover what nobody ever mentioned to me about Jet Set Radio, including any review: Jet Set Radio has a plot line! If I wrote that the setup involves a turf war between Rudies tearing up the streets of near-future “Tokyo-to” with battery-powered rollerblades while also battling the gentrifying “21st Century Project” directed by a united front between the Tokyo Metropolitan Police and an international corporate conglomerate called the Rokkaku Group, I would no doubt surprise most readers. And that’s just the first chapter!

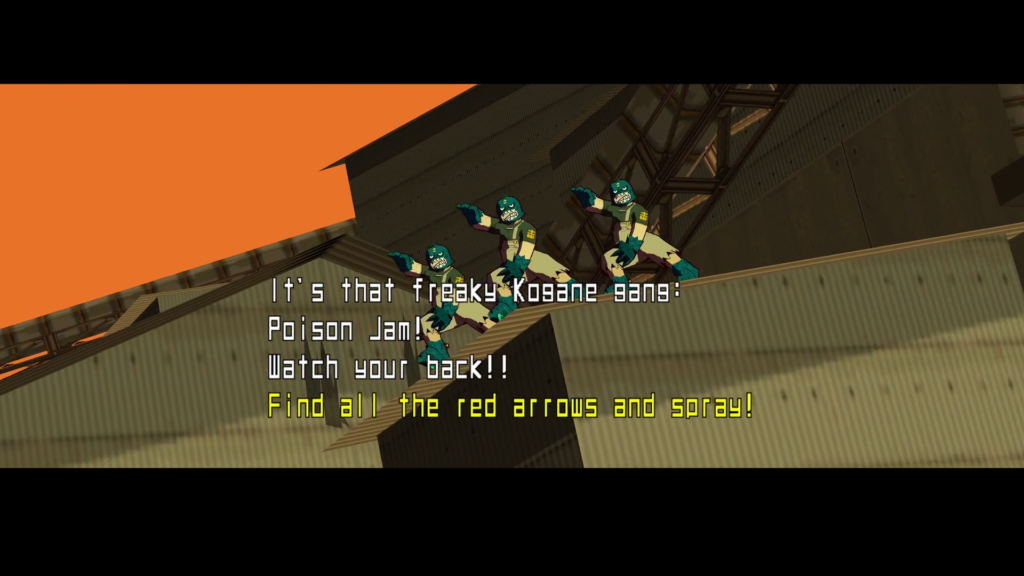

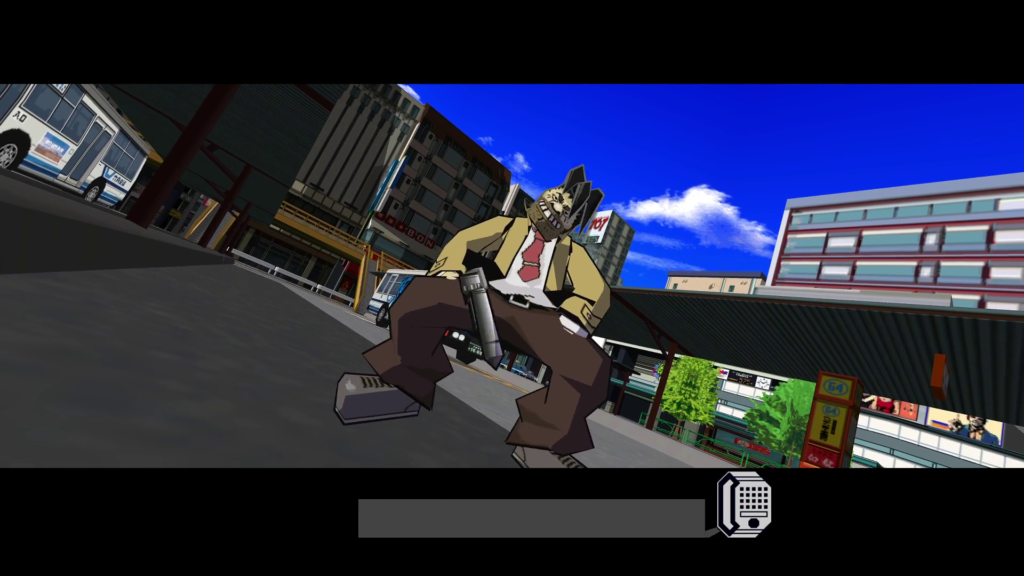

The GGs face three rival gangs, the Love Shockers, Poison Jam, and Noise Tanks, each sticklers for tailor-made uniforms like in The Warriors. Jet Set Radio underutilizes their gimmicks, though. For example, Poison Jam are slasher movie fans who dress up in fish-monster costumes, each as burly as the Shape that haunted Haddonfield. You can see one of them in the middle left of the picture at the top of this post. There should have been some scene where the player has to escape from Poison Jam in a horror movie pastiche or parody, maybe have the Poison Jam boys use big knives in their stunts or fill their spray cans with fake blood or something. Instead, the horror theme is only skin-deep. More an amphibian theme, really, since they can fill the GGs’ garage with frogs.

The second chapter introduces two American Rudies, Combo and Cube, who travel to Tokyo-to after their friend Coin goes missing in connection with the Golden Rhino, a league of assassins. Combo basically usurps Beat and DJ Professor K, becoming the new hero and narrator. When I was suddenly skating around an unfamiliar city dodging classy gangsters while Rob Zombie music (!) played, I knew there was more to Jet Set Radio than I thought.

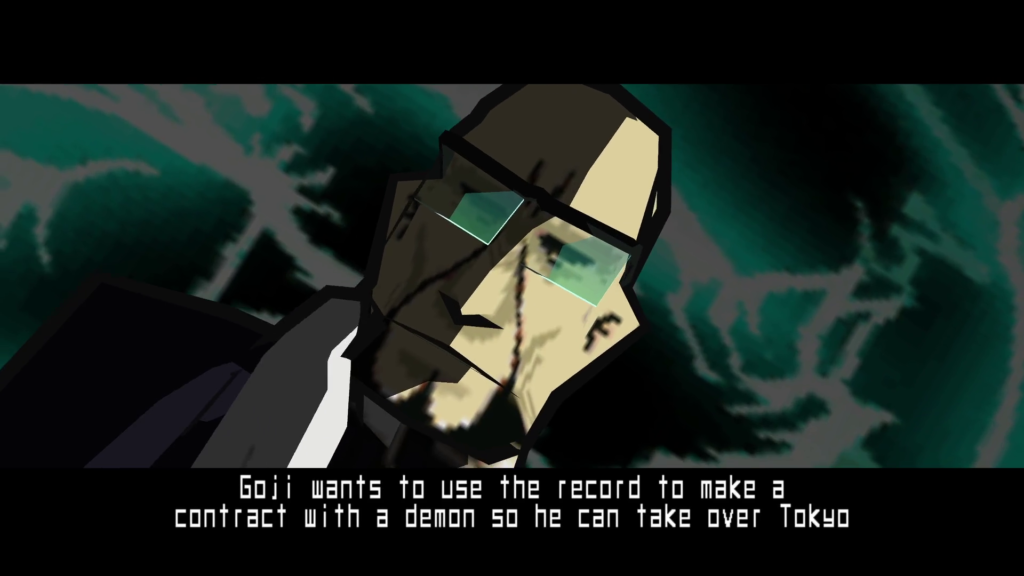

In the third chapter, it turns out Goji, the head of the Golden Rhino and the Rokkaku Group, is searching for the “Devil’s Contract,” a vinyl with the power to summon a demon. In the end, the GGs kill Goji and blow up his headquarters. Combo becomes bizarrely philosophical: “Well, they say that money is the root of all evil. Maybe it really can twist the hearts of men. It turns out the record that Goji was looking for, the ‘Devil’s Contract’ was [sic] just an old indie record, a hoax. Maybe his twisted mind created the whole story out of rumors and superstitions in order to try and sate the demons of his own heart.” More startling is that you don’t save Coin—he’s dead! The Golden Rhino killed him! This is like if Super Mario ended with Mario finding Peach’s corpse. Though the English script obfuscates this detail, the visuals still include it. Combo doesn’t seem terribly cut up.

Bad dubbing joins the chaotic cops and traffic, weird story, and unintuitive levels to increase the sense of derangement. Dialogue gets cut off awkwardly and falls out of sync with the subtitles, as though the characters are too passionate for the programmers to keep up. A sense of frantic energy predominates. Every character (except, ironically, whomever the player is currently controlling) dances constantly. Constantly. And with such a bopping soundtrack, why wouldn’t they? Under the GGs’ electrifying influence, I’ve started idly dancing in real life too.

Aside from the cel-shaded graphics, fans best remember Jet Set Radio for the peppy hip hop, rock, and techno soundtrack composed by Richard Jacques, Sawada Tomonori, and, now popular on Twitter, Hideki Naganuma. Most of the music isn’t to my taste, consisting of funky beats with vocal samples spliced into gibberish. My favorite tracks are “Humming the Bassline” and “Magical Girl,” though in the latter I misheard the lyrics as “She’s a much better girl!” “On the Bowl” sounds Sonic Heroes-ish, though easily better than anything in Sonic Heroes. In addition, though the release history is somewhat complicated (there were like four different versions back in 2000), the soundtrack also features a few other artists including Cold and, as I mentioned, Rob Zombie.

The title refers to the “pirate radio station” Jet Set Radio, hosted by the mysterious DJ Professor K, voiced by Billy Brown. Presumably Jet Set Radio is hosted from some offshore location à la Radio Caroline. Unfortunately, the player never learns if Professor K lives in a Principality of Sealand-style base. The idea is that the very not-video-game-like music the player hears is diegetic, the Rudies constantly listening to these pirated bops on Jet Set Radio as they possibly literally paint Tokyo red. Professor K narrates the first and third chapters. Scenes of this DJ, lips bright orange and hair literally dancing, spittle flying while he hams it up in front of a speaker array, become the most memorable single visual in Jet Set Radio. Similarly, the most memorable line is Professor K shouting: “JET SET RADIOOOOOO!” No idea why, in one cutscene, Professor K bothers to use a puppet prop display of flying saucers in his studio when his listeners can’t see him. But hey, that’s Professor K for you. The Grind City levels, set in the United States, feature Cold, Rob Zombie, and other guest artists, cleverly implying that Combo and Cube are listening to their own, different pirate radio station. (Since Professor K is apparently Japanese, as are the dark-skinned GGs Garam and Piranha, this is probably an early case of Black Japanese representation in video games.)

After the credits, Professor K reappears to end the story on an even more confusing note than Combo. “What’s that? You think I just made all that up? Ha ha ha! Sure, sure, okay. But watch out! Someone just might have their sights on Shibuya-cho again! On the street, there’s no such thing as ‘The End!’” The closing cutscenes establish that the Love Shockers, Poison Jam, and the Noise Tanks have returned and that Goji’s son, identical to Goji, has inherited the Rokkaku Group. Jet Set Radio resets to chapter 1, trapping the characters in some kind of eternal loop. But why? Does this barebones plot mean anything, or did someone at Sega need to meet a deadline? Perhaps it suggests that the battle between urban communities and gentrifying private interests wielding the police is an eternal one.

I appreciate the childishness of Jet Set Radio’s understanding of counterculture. Somehow, graffiti threatens Tokyo enough that Officer Onishima is shooting teenage girls in the head point-blank. But I could accept this as a conflict about real estate prices or something. When the more serious Golden Rhino replaces Onishima as the enemy faction, though, their goal is explicitly to take back the pieces of the “Devil’s Contract” vinyl. Yet somehow the Rudies vandalizing their Golden Rhino posters and mascot statues is enough to foil their plans, as if it would even be relevant. These guys literally have snipers on rooftops and death squads flying around the streets on jetpacks. I don’t think they would care. And they don’t, since they get the “Devil’s Contract” anyway. In the final boss fight against Goji, graffiti causes towers of his headquarters to collapse, somehow, and tagging his bald scalp causes him to go hurtling off the rooftop to his death! Goji might actually commit suicide here because you’ve tagged his head? When he falls, he shouts, “Geronimo!” so it seems intentional. This is the sort of magical overemphasis on a single, weird gimmick I put in my stories when I was an elementary schooler. It is so ludicrous as to be astonishing. The only logical use of graffiti as a weapon is spray-painting the windshields of attack helicopters. Judging from the resultant fiery wreckage, the Rudies are murdering their pilots! Jet Set Radio is bonkers!

Aside from graffiti, counterculture means performing dangerous stunts with roller skates and listening to indie music while performing wholesome dances in your garage. The people of Tokyo seem utterly indifferent to the Rudies and the cops, hopping out of your skater’s path but otherwise ignoring you and your graffiti. Jet Set Radio’s counterculture is not a social movement aiming, as Professor K would have it, to “turn these dirty streets into one big dance party” in defiance of Rokkaku corporate homogeneity. Instead, it is a bunch of young people immersed in what was considered cool back in 2000, and that included aimless, somewhat condescending, vaguely anti-capitalist nonconformity that could as easily turn fascist like in Fight Club.

Though it is hard to judge the intentions of Beat, Gum, Onishima, or anyone else. None of the characters receive any development. They are pure ciphers. All one needs to know about Piranha or Tab is what one assumes from their appearance. In the world of the Rudies, social introductions are stunts, graffiti, and your street name. No need for conversations or beliefs. Jet Set Radio is a fantasy that the inchoate rebelliousness of the bored teenagers to whom Sega marketed it was itself capable of erupting into social change, a fantasy that strips rebellion of any ideological coherence or legitimate radicalism that might trigger a moral panic. It is like Sonic the Hedgehog, in that way. This dangerous punk game opens on a hilariously square disclaimer warning the player not to create graffiti in real life. Vandalism is a crime, you know! This attempt by some Japanese video game nerds to capture bleeding-edge urban street flavor results in something so corny it somehow becomes cool again, which, incidentally, is also like Sonic the Hedgehog at its best.

I will say that, especially for mainstream pop culture detritus from 2000, Jet Set Radio is surprisingly anti-police. The heavily militarized cops are absolutely the bad guys, as cruel as they are incompetent. Corrupt, too: the maniacal, screeching Onishima ups the police response to the Rudies specifically to bulldoze local culture for the the Rokkaku Group’s gentrifying 21st Century Project. A corporation has effectively usurped the Tokyo government. Despite the bright colors, Jet Set Radio is oddly cyberpunk. In addition to what the mission flavor text attributes to cowardice, this might be why Onishima allows the Golden Rhino to rampage around Tokyo, bombing crowded public areas and crashing cars into walls. The overfunded police do far more harm than the Rudies. These cops’ tanks, for example, flatten whole rows of civilians’ cars.

The player is encouraged to tag Onishima, leaving him to shout “Damn!” and pout like a child. The Steam achievement is called “Cop Sucks.” Our cool cat Professor K mocks the police, too: “Even the Keisatsu tune in here when they’re not eatin’ donuts.” After the George Floyd uprising, I no longer find the idea of cops deploying tear gas on a teenage punk as much of a hilarious exaggeration as I might have before. Instead of tear gas as a thing that happens far away on news broadcasts, the use of chemical weapons against civilians now feels much more traumatic and real. If Jet Set Radio occurs near 2020, I suppose the police brutality is oddly prescient.

The overarching theme of Jet Set Radio is looks over substance. The central gameplay, throwing graffiti onto a wall, emphasizes the importance of looks. The Rokakku Group plasters literally paper-thin propaganda over the walls, and you respond by literally painting on top of it. All symbolic struggle and no real struggle. Naganuma even edited the song lyrics to be meaningless—catchy but meaningless. Jet Set Radio has shallow and sloppy level design, in many ways, but the cool cartoon graphics and funky music made people think it was brilliant. Jet Set Radio’s creative process organically led to this ethos of aesthetics over all else.

In the (underwhelming) documentary included with the HD remake, several of the crew at Smilebit talk about the development of Jet Set Radio. Award-winning art director Ueda Ryuta describes his underlying philosophy in designing the characters: “At that time, when I was making the character, what I thought was that I wanted to make it more like an icon. In other words, not like a human but a character like a symbol.” Beat, Gum, Combo, Cube, and all the rest are shallow images instead of well-rounded characters but intentionally so. Similarly, the director, Kikuchi Masayoshi, says this: “We started to shape it from visual impact and imaging. So in the beginning, for the inline skate game, we had only a vague idea. […] The point is, we could have made it into an adventure game or an RPG.”

The foundation undergirding Jet Set Radio is no central mechanic, no thematic conceit or creator with a vision they wanted to realize. It is all appearances, all style. Substance was secondary, resulting in barebones gameplay and story. But substance and style are inseparable and in that way result in an awkward, frustrating experience, shallow in its skating and finicky in its handling, whose sheer confidence and dazzle got me hooked.

There is at least one way way, besides the dancing, the aesthetic feels genuinely radical, and that is in the Rudies’ hip street names. These young people invent their own identities as “Beat” or “Mew” instead of accepting an inherited one. Only the villains use their real names: Onishima and Goji. In Goji Rokkaku’s case, the continuation of his name ensures the perpetuation of the Rokkaku family wealth, of the unjust power structure that the Rudies will battle as long as the streets exist.

Jet Set Radio feels more like a proof-of-concept than a finished product, exactly the kind of half-baked idea with which Sega experimented at the turn of the millennium. Supposedly, Smilebit ironed out the kinks in the Xbox reboot Jet Set Radio Future (2002), producing a tighter, faster, smoother video game that even features a more elaborate story. But there is no computer port of Future as yet, so I remain agnostic. One thing I do know for sure about Future is that DJ Professor K’s hair has gone white.

Skating down streets while the spray painting minigame and occasional instant replay moments of presumably cool jumps interrupted the flow of play, I found myself thinking about one of my all-time favorite video games, Katamari Damacy (2004). In several ways, Jet Set Radio is a predecessor. Like Katamari, Jet Set Radio features defiantly cartoonish, colorful aesthetics and a central mechanic so unique that it is difficult to qualify. It features a simple yet ostensibly confusing control scheme and casual, pick-up-and-play quality. It features timed missions in initially small environments that become larger and turn out to be physically interconnected. Exposition comes from a visually distinct, comedic character who narrates the action after every single level—Professor K and the King of All Cosmos, respectively. The soundtracks feature energetic, lyrical and contemporary tunes well outside conventional video game music. The player is encouraged to replay the same levels over and over, gaining proficiency, memorizing their tricks. I have no idea whether Takahashi Keita liked Jet Set Radio, but it is a bad sign if one video game leaves me wanting to play another. The Jet Set Radio formula of Shibuya, stylized super-cool characters, and an eclectic modern diegetic soundtrack also presages The World Ends with You (2007), especially now that its sequel is moving into 3D cel-shaded graphics. While Jet Set Radio’s constant dancing and bright colors explode with youthful exuberance, developers have taken cel-shaded graphics to more transcendent or at least more intriguing places in The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker (2002) and Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus (2002) and killer7 (2005) and Ōkami (2006) and Catherine (2011) and a hundred others. Still, I guess that I should give Jet Set Radio some credit. I enjoy clunky video games, and part of what makes pioneering work so tough is its retrospective modesty.

As of June 2021, at least two video games appear to be “Jet Set Radio clones”: Hover (2017) and Team Reptile’s forthcoming Bomb Rush Cyberfunk. There is also a TRPG called Underground Broadcast, but I know nothing about TRPGs.

By the way, Jet Set Radio is not the first cel-shaded video game. Mega Man Legends came out in 1997.