Published 27 January 2022

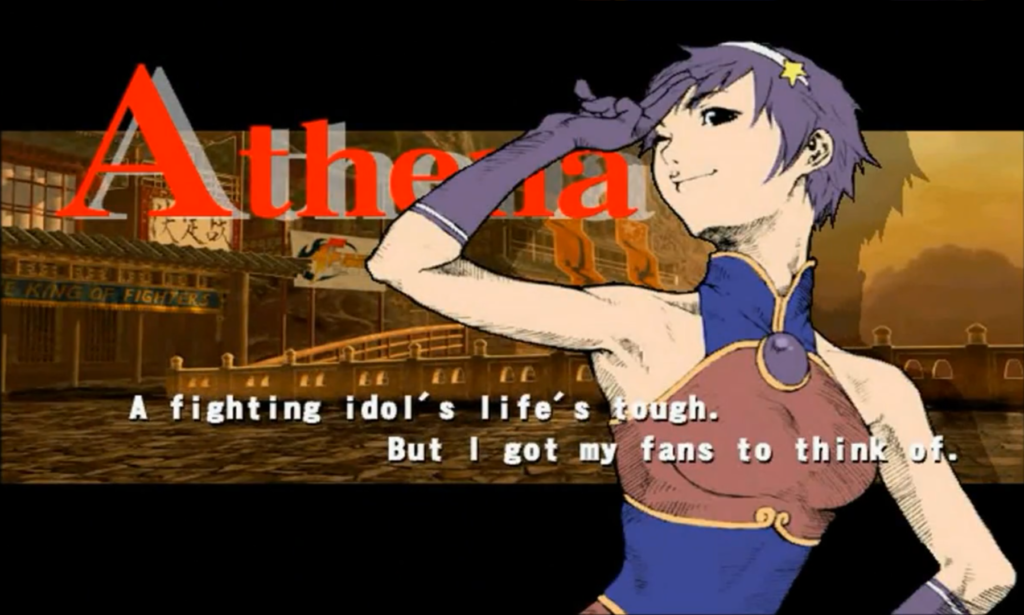

The magical girl- and idol-themed 1987 SNK arcade game Psycho Soldier is best remembered today as the debut of Asamiya Athena, purple-haired staple of The King of Fighters franchise and one of SNK’s main mascots. I played Psycho Soldier in the SNK 40th Anniversary Collection.

In 1987, SNK specialized in military-themed run-and-guns like Ikari Warriors, a Rambo copycat whose sequels hurtle off the rails with fantasy and sci-fi nonsense, and Guerrilla War, in which the players control Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, as well as shoot-’em-ups like TNK III and Alpha Mission. Given this background, the title “Psycho Soldier” might suggest a particularly sadistic military shooter. However, SNK’s developers took after other Japanese pop culture of the ’80s, conflating the English words “psycho” and “psychic.”

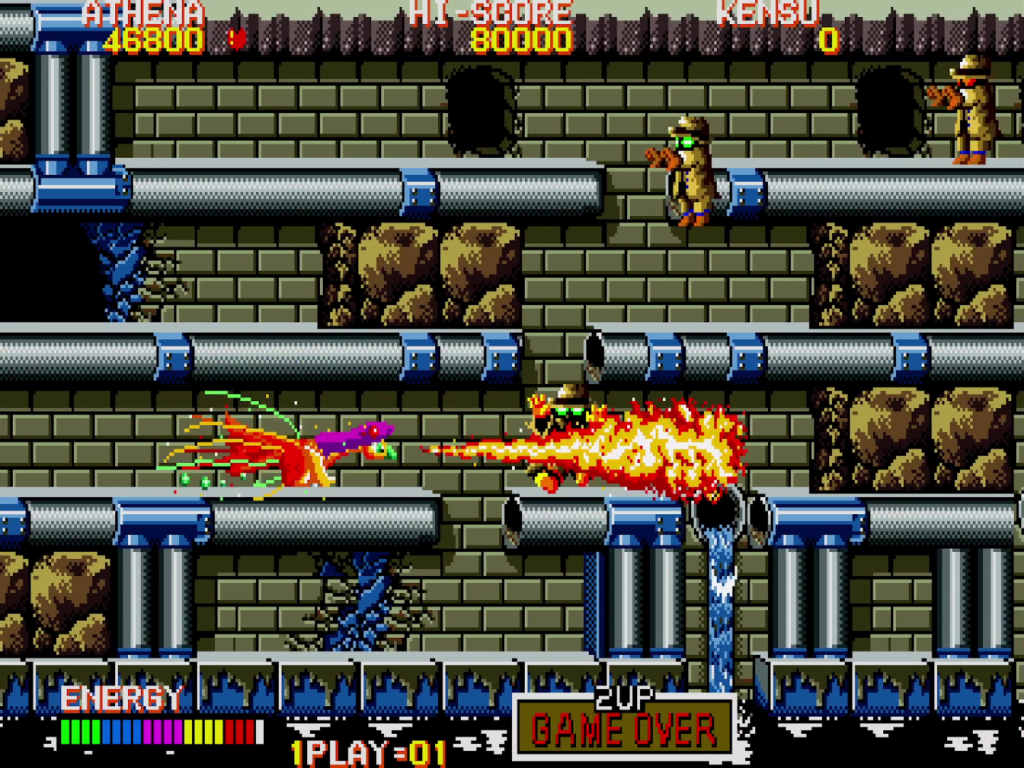

Player one controls Asamiya Athena, the heavenly Athena from SNK’s previous fantasy sidescroller Athena reimagined as a joshikousei, pop idol, and, yes, psychic warrior capable of firing blasts of energy from her fingers. Player two controls Sie Kensou or “Kensu,” a tough guy with a Rambo-style headband. Kensou would be at home in a typical SNK military shooter. But he too is a psycho soldier and plays guitar in Athena’s band. The story is that these two appear to stop a Lavos of a monster called Sigma (or Shiguma) that has awoken from deep within the earth. But Athena and Kensou might be aliens themselves, given that flying saucers beam them down in the opening and after losing a life.

In the Japanese version, beneath crunchy audio compression, Athena speaks with confidence, except when she comically trips over obstacles. In the English release, Athena speaks in a monotone foreign (Japanese?) accent while stumbling through a few English words seemingly half-asleep. “Athena I will go.” Wonder what the story behind it is? They might have had some programmer or a friend do the English VA. What surprises me is that a product so heavily ensconced in Japanese pop cultural tropes got an English release at all back then.

Psycho Soldier is an auto-scroller, always forward and never backward. There is no longer platforming like in Psycho Soldier’s predecessor, Athena. Instead, each stage is tiered between four levels. Assuming a given level has a platform to walk on and no obstructing walls, the player can hop between levels at any time. This system, complete with a two-player feature, seems copied from the 1984 Capcom arcade game SonSon.

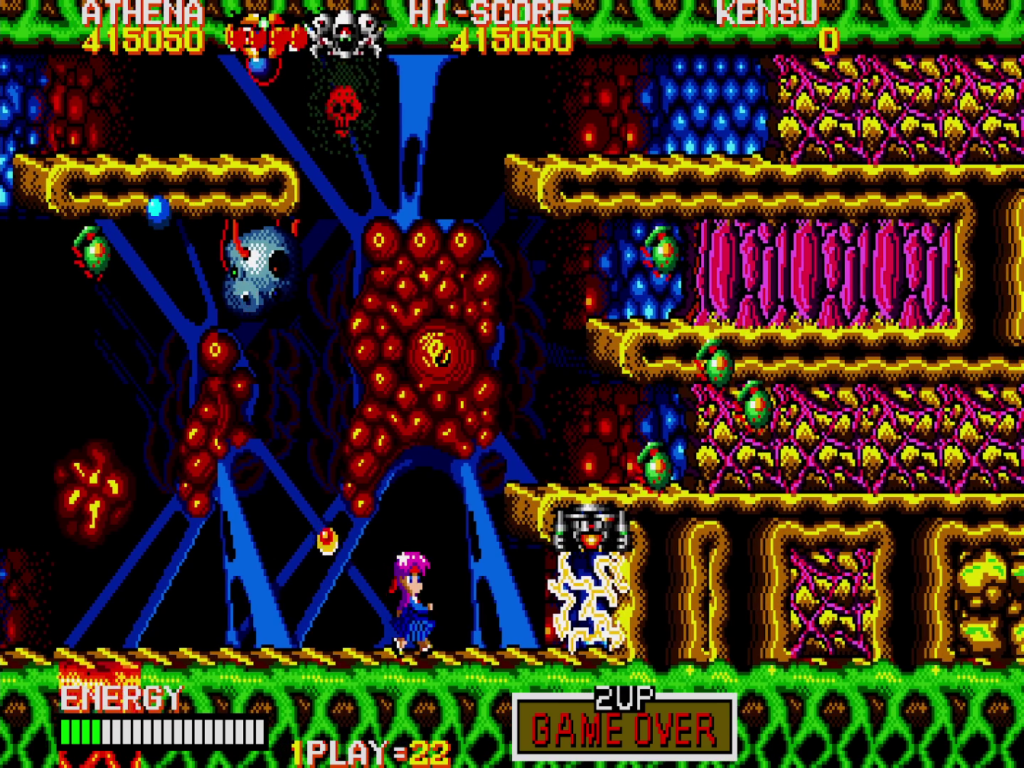

Complicating the process of running right are Sigma’s minions, primarily insect-, lizard-, and fish-men whose projectiles and movements become increasingly aggressive and difficult to avoid. Another issue are destructible barriers that often conceal powerups, such as magic swords straight out of Athena that somehow strengthen the Psycho Soldiers’ psionic beams. Only in the final stage, when the walls are living tissue that rapidly regrow to crush Athena and Kensou, do the barriers threaten not only to squish one at the side of the screen but to reform on top of Athena and Kensou and squish them that way instead. The purposes of many items, such as a levitating infinity symbol or the bouncing rainbow block, are unclear. But in an arcade game, one does not worry—one grabs stuff. Though this can be an issue when it comes to red skulls or the skull-emblazoned energy fields, both of which drain Psycho Energy.

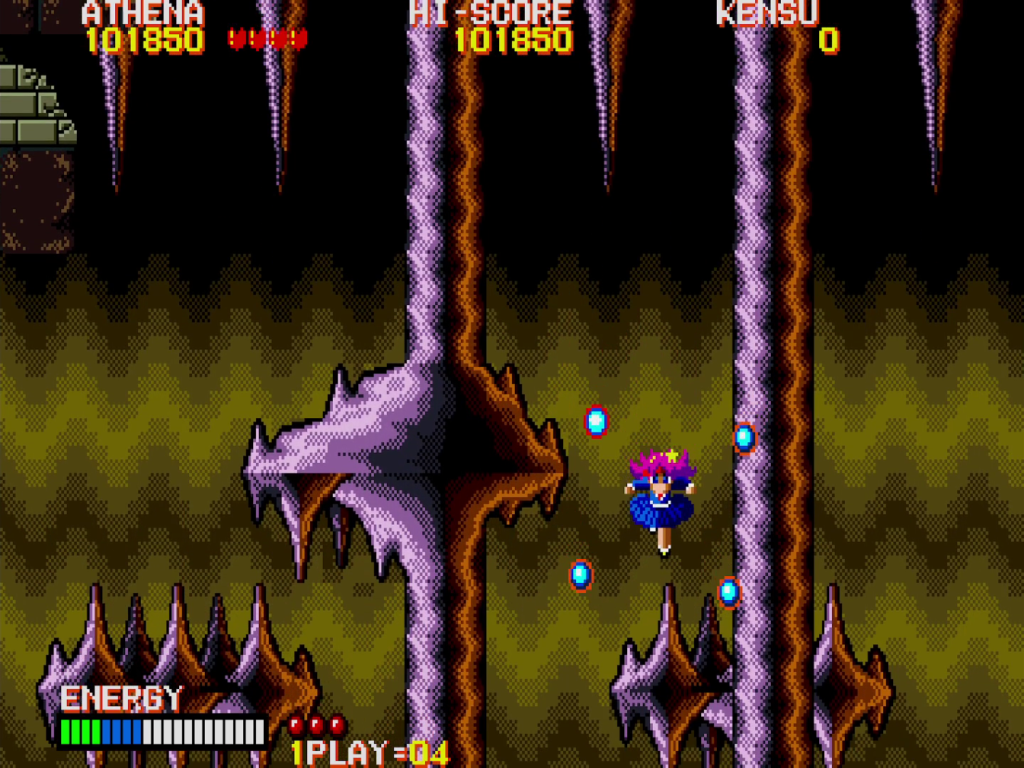

This brings us to the meatiest of SNK’s alterations to the SonSon formula, the two unique stats Psycho Soldier asks the player to track in addition to lives and score: Psycho Energy and Psycho Balls. When the flying saucer beams Athena or Kensou in, each begins with four Psycho Balls orbiting their body. For the price of Psycho Energy, the Psycho Balls can absorb some enemy projectiles. When the beams Athena and Kensou shoot from their fingertips prove insufficient, Psycho Balls can also be shed in powerful projectile attacks, though what form the attack takes seems to vary with the Psycho Energy level.

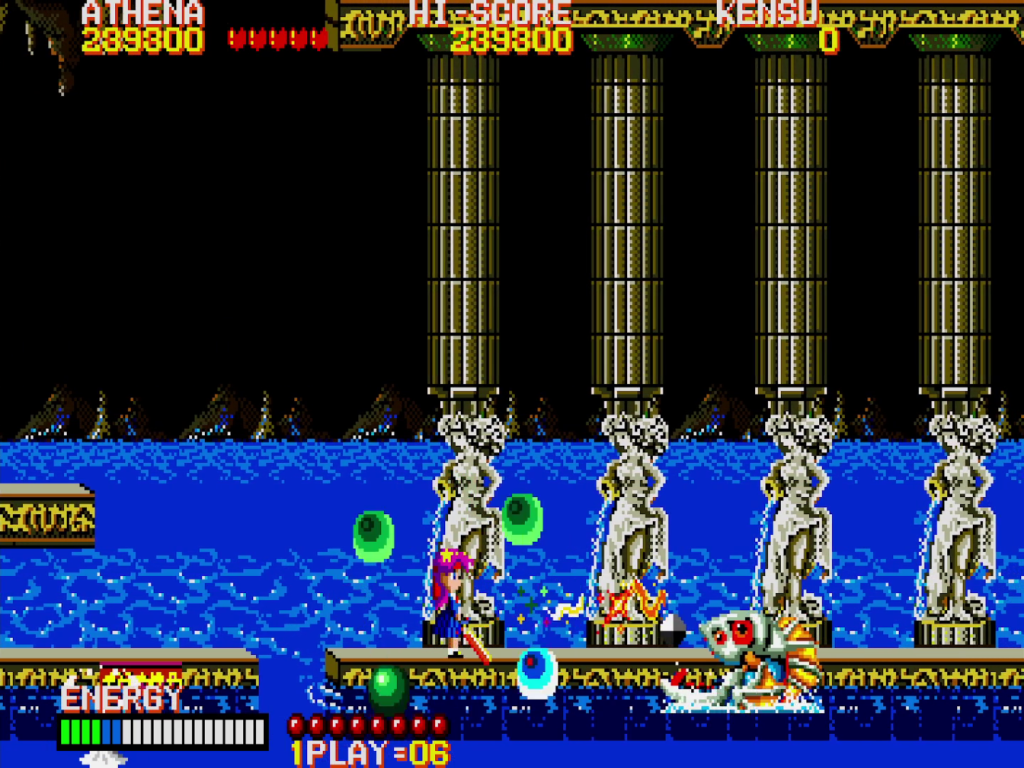

The player can gain more Psycho Energy and additional Psycho Balls from canister-shaped energy fields found inside destructible walls. When both stats are maxed out, the Psycho Balls swirl around the character in a rainbow blur, absorbing most enemy fire and allowing a special attack to clear the screen in spectacular swirls until, from blows or grabbing a skull, the Psycho Power runs out again. After extra lives, which take the form of playing cards, the rarest items are human-sized green eggs. If cracked open, the egg reveals a powerup that transforms Athena into a phoenix and Kensou a dragon, granting invincibility and deadly fire breath but removing the ability to turn around. This impressive powerup maxes out the Psycho Energy meter and will list until, from the enemy onslaught, the Psycho Meter ticks down to zero again. Shapeshifting goes beyond the range of what I’d assume an esper could do! But sometimes the green eggs are full of deadly Sigma larvae instead, adding a Mario Party-esque chance element that I imagine could make for a fun time with a second player.

Psycho Soldier consists of six stages. Each concludes with a screen-height barrier that collapses upon the defeat of the boss, allowing onward progression. With the exception of the fifth and sixth, a giant fish and levitating rock monster respectively, every one of these bosses are the barriers. Most of the bosses are simple—or are if the player can dodge their attacks—but the final boss, a two-headed dragon whose flesh and organs coat the walls, must have some trick to it. I confess that, powered up all the way and with the save states and rewinds the 40th Anniversary Collection permits, I can barely beat the thing! This might be in my head, but I think the final boss has less HP in the Japanese version, which means there is no reason to play the overseas release except to hear the inferior English audio.

After each boss, the action continues with the heroes walking forward through barriers replete with powerups and then jumping deeper into the earth. This system, with the boss as a barrier blocking progress to the next area, is also copied from SonSon.

The first couple stages toss the player into cities that, facing Sigma’s onslaught, are in the throes of apocalyptic ruin. Belying the potential darkness, the swarming insect people and shambling raptors in trench coats speak in incongruous comical voice samples. The peppy “Psycho Soldier Theme” seems to say, “You can do it! Fire, fire!” instead of “Humanity has fallen.” From there Athena and Kensou dive deeper into the earth, facing tougher enemies and sometimes such a chaos of sprites the game slows down.

They uncover ancient Hellenistic ruins (is this city in the Mediterranean?) and, in the tough-as-nails final stage, climb into a giant Xenomorph mouth to face the R-Type-style organic horror of Sigma itself, walls covered in blue scales and ribbed flesh and enemies like levitating organs—quite the shift. One particular monster, resembling a floating green liver with a tentacle, seems impossible to dodge. While the narrative progression is nonsensical, the tonal change results in the journey feeling more meaningful, and a goofy EXIT sign behind the final boss and a credit sequence with Athena singing help the darkness go down smooth.

The lack of level breaks results in a strong sense of continuity. I base my “stage” divisions only on the placement of boss fights. As with SonSon, one could argue that Psycho Soldier is, instead, a single continuous stage. I almost didn’t notice the bosses—just another thing to blast through while the same arcade music farts out. Still, despite the colorful heroes, most of the stages are repetitious and generic stone. If Athena has any advantage over Psycho Soldier, it is the differentiation between its levels, such as one in which Athena becomes a mermaid. I wish more of Psycho Soldier’s stages had half the personality of its characters.

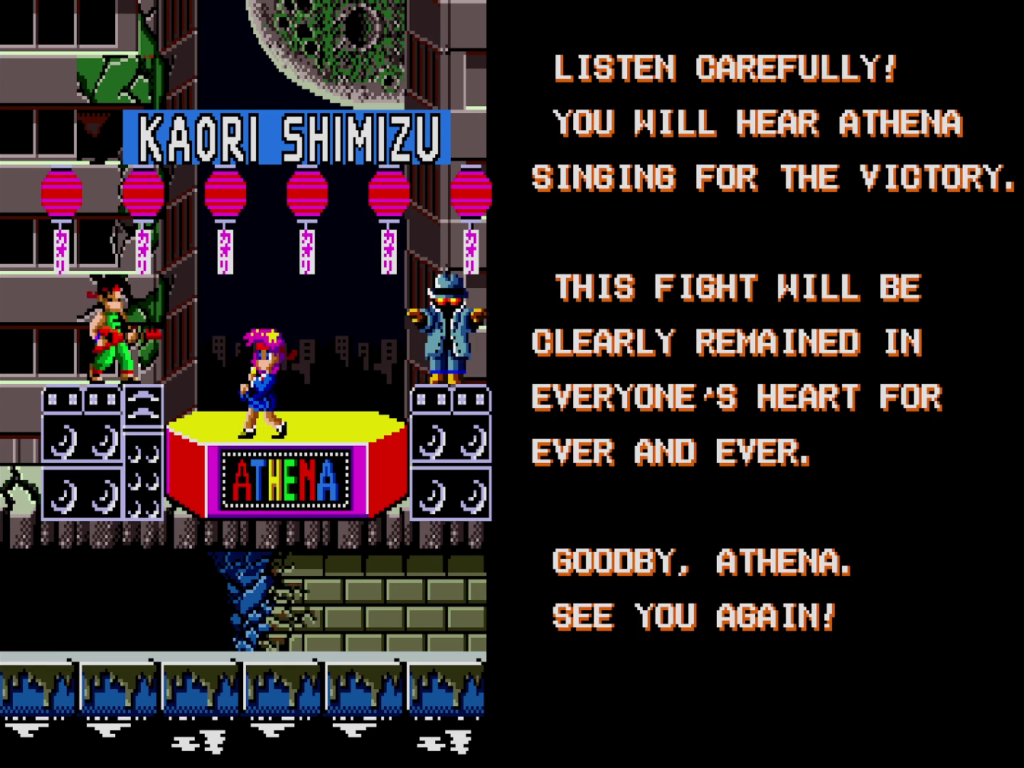

Psycho Soldier is notable as supposedly the first video game to feature a song with full lyrics. “FIRST TIME IN VIDEO GAME. ATHENA SINGS LIVELY,” as the marketing boasted. Within the limitations of the crunchy compression and the arcade sound chip, the “Psycho Soldier Theme,” sung by Shimizu Kaori, is an ear worm. According to the SNK Wiki, here are some translated verses:

“She hides the Psycho Power in her heart

To run on the endless path,

Though she can now no longer see the blue sky.”

I found myself humming it all day every day for at least a week after playing Psycho Soldier. SNK released a longer, super-’80s uncompressed version with the Famicom port of Athena. This bright pink cassette tape is better than the video game it came packaged with! The song’s lyrics atrophied away in The King of Fighters until Sakurai thankfully resurrected them in Super Smash Bros. Ultimate. The American version of Psycho Soldier features an uncredited woman singing a rewritten English version that is equally corny but in an incompetent way. Compare the below to verses to the above—they correspond to the same lines:

“She’s just a little girl with power inside, burning bright.

You’d better hide if you are bad—she’ll get you!

She’ll read your mind and find if you believe in right or wrong.”

Athena and Kensou are literally thought police! How terrifying! But they’re battling an ancient, world-destroying monster, not crooks whose minds they need to read. In contrast, the Japanese lyrics describe the abilities displayed in-game. But the chorus is English in both versions:

“Fire, fire, Psycho Soldier!

Fire, fire, Psycho Soldier!”

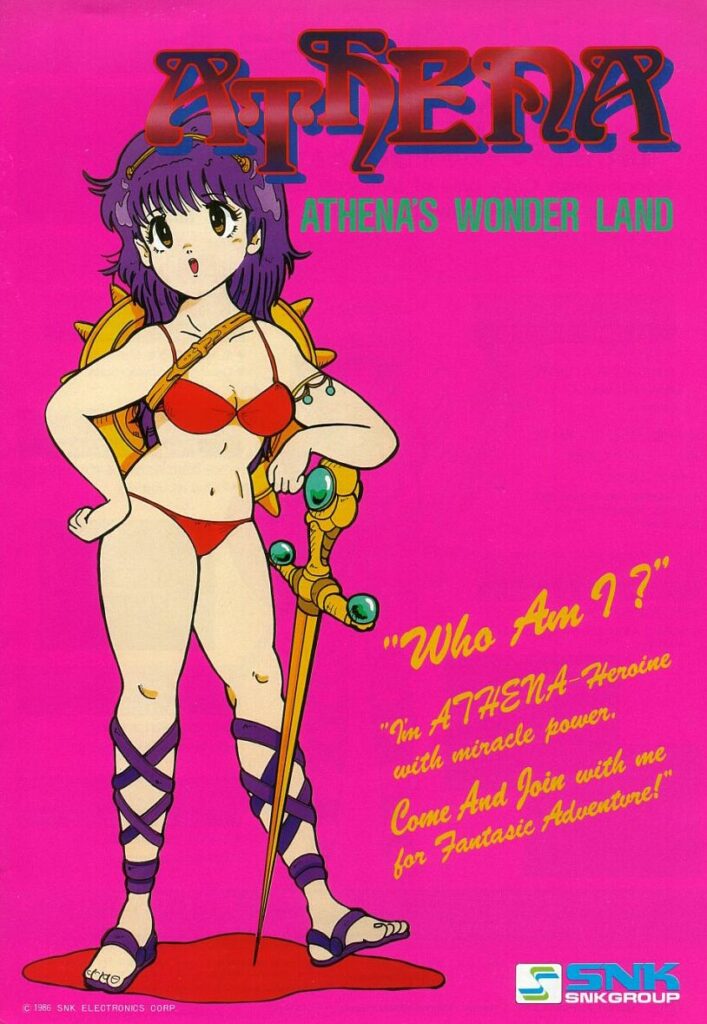

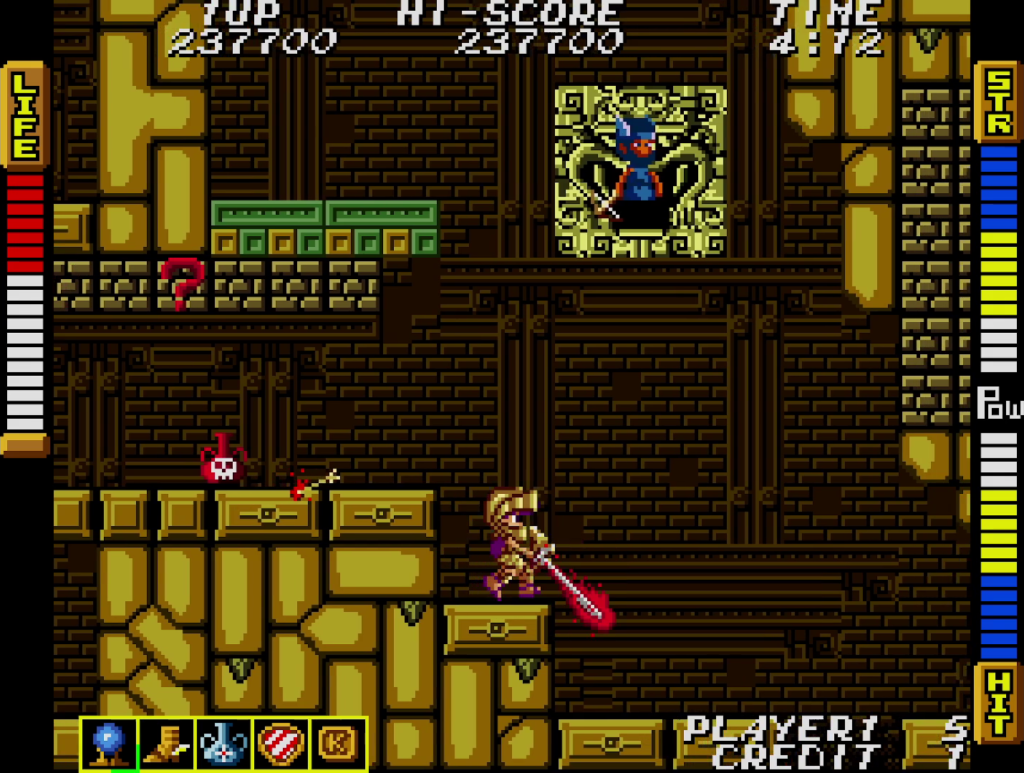

This brings us to Athena, whose shortcomings shed light on the sequel’s strengths. The story, more fun that the setup of Psycho Soldier, has a whimsical Alice in Wonderland vibe: Athena (Asamiya’s ancestor), a divine princess, defies the stuffy boredom of Heaven, dives down a hole, rips off her clothes, and fights monsters. Athena is a sidescroller featuring “RPG elements,” meaning that the player gathers pieces of equipment to become stronger (and get Athena dressed again). The gameplay focuses on powering Athena up enough to overcome the enemies and bosses. Athena must go from kicking enemies to beating them with a wooden club to blasting through several at once with a magical fire sword. The player can move forward and backward, albeit to a limited extent, encouraging exploration and experimentation. As in the sequel, breakable walls conceal powerups and other items, but enemies also drop armor and weapons.

An early case of sex appeal selling a video game, Athena is famous for its bikini-clad heroine designed by Nakai Toshiyuki. The developers insist they intended to suggest Athena’s initial weakness in contrast to her later armor, perhaps pulling the concept from Konami’s Ghosts ’n Goblins. Whatever the intention, it is not Athena’s vulnerability that SNK’s marketing has used the red bikini to emphasize. Even Asamiya dons it now and then. (Though let’s be real—that “bikini” is underwear. Would Athena have been wearing a swimsuit beneath her dress?)

While Athena performed well largely on the basis of starring a mostly naked anime girl, Psycho Soldier is more fun. Athena might appear freeing relative to the autoscrolling of Psycho Soldier, but this freedom is an illusion papering over infuriating difficulty. To stand a chance, the player must memorize viable paths through stages via trial and error. Worse, Athena’s default kick and jump cannot break walls. She requires weapons and helmets to do the job. But when I need to break walls to find items, the resultant catch-22 wrecks the whimsical tone the devs seem to have wanted. Entering later stages with a full arsenal seems essential, being reduced back to the red lingerie condemning the player to a game over à la Gradius.

The backtracking in Athena is limited too, landing at a maddening spot: the uncertainty of open-endedness but with a time limit and enforced forward movement denying the opportunity to genuinely explore the level. Despite the rewind feature of 40th Anniversary Collection, this quarter-guzzler (or fifty-yen-coin-guzzler) proves too tedious. While the nonstop action that the autoscrolling enforces results in a shallower experience, the SonSon-inspired streamlining permits Psycho Soldier more satisfying and less frustrating gameplay. In contrast to the punishing deaths of its predecessor, Psycho Soldier allows any attack to break walls. The default simply takes more time than using a sword. And death does not feel like a play-ending condemnation: one always moves forward, even when the Psycho Soldiers are re-spawning, instead of flailing around trying to get past the same enemies.

All spectacle and zero thought, SNK’s arcade titles achieve rare heights of brainless cheese. Psycho Soldier follows this tradition. The action on its busy screen, explosions and buzzing insect men dissolving in psychic blasts, armored rhinoceros-shaped alien bugs shooting electrical beams while our fighting idol cuts them down with her sword, feels paradoxically toothless, immaterial, lacking the punch of even Mario kicking a shell. Still, Psycho Soldier is wacky, challenging, and, at only about forty minutes long, worth a look for the historical interest in an SNK mascot if nothing else. How might video game history have gone if Athena had caught on instead of Mario?

Furthermore, with the mishmash of espers, sci-fi, ruined cities, gruesome monsters, and a magical girl in a sailor uniform, Psycho Soldier sticks out most not for its graphics, SonSon-imitating gameplay, or even lyrical music. Rather, what sets Psycho Soldier apart is that, aesthetically, though not sexual, it is an arcade game equivalent of the anime that catered to the emerging “otaku” audience back then, wacky (and likely sexist) romps like Project A-ko or Genmu Senki Leda. How many video games catered to this niche in 1987 I am not sure, but Psycho Soldier must be an early example. The only previous one not based on an existing anime that comes to mind is Wonder Momo, which Namco released a single month before. For someone who digs the vibe of this ’80s anime schlock, Psycho Soldier is like junk food. Or for someone who just digs retro Japanese pop culture, which oozes from every inch of Psycho Soldier. Even the Sigma insect monsters, with their big, blank bug eyes, recall Kamen Rider.

A few words on the luxurious 40th Anniversary Collection container: it features quality emulation, except for the NES games whose sound seems to sometimes skip, and a large selection. For those not up for the high difficulty of arcade games, the Collection features save states and rewind features. In a fantastic and, so far as I know, unique addition, SNK also includes prerecorded playthroughs of every title. At any point in these playthroughs, the player can stop the video and take over from where it left off. These are great accessibility features for those of us without the time or inclination to master Athena or Ikari Warriors but who want to see them through. Scans of promotional material and concept art, including the (untranslated) Athena player’s guide/manga, sweeten the package. With twenty-five arcade and NES games available in both American and Japanese versions, this broad collection might not accomplish the all-time great status of the PS1 Namco Museum series but comes closer than most.

SNK 40th Anniversary Collection is currently available on Nintendo Switch, PS4, Xbox One, and Windows at GOG and Steam. The Collection also includes Athena and every other SNK arcade title I have mentioned. In addition, Psycho Soldier is available as a standalone purchase on Switch and PS4 at the ridiculous $7.99.