Published 7 February 2022

From Smiling, alias of indie developer Min-Taylor Bai-Woo, created a number of intriguing titles before mostly vanishing from the internet. From Smiling was most productive in 2014. One of that year’s six titles is the simple though powerful Frail Shells.

You can download Frail Shells at itch.io.

Frail Shells is one of those video games which to describe is to give away the twist. It is less than ten minutes long, yet the screenshots on the itch.io page reveal nothing. But to describe it, I must spoil it. Something like Nier could be reviewed without stating the twist because there is much more to it. But Frail Shells is more twist than anything else.

The opening setup, something like Bad Dudes, promises typical genre cheese. A radio crackles your mission:

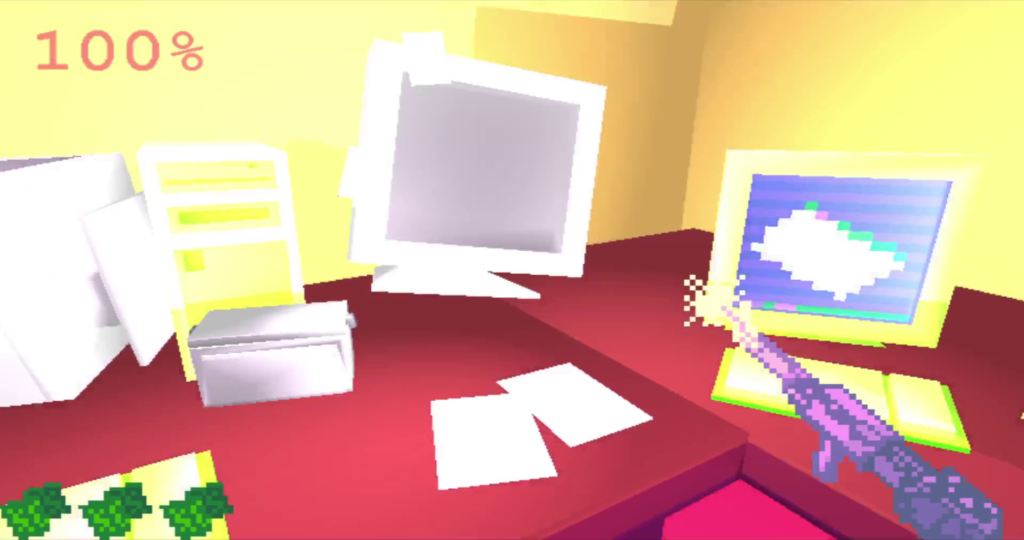

Running through a strangely pink low-poly battlefield, Frail Shells is a banal, barebones FPS. Stationary enemies, flat sprites in a 3D environment, fire at regular intervals. Upon being shot, they let out a scream, hurtling away like paper cutouts, their masks establishing standard enemy dehumanization. But Frail Shells is not an FPS at all, for after climbing the hill and gunning down these faceless mooks as a typical FPS mass murderer, we reunite with Mackenzie, and a shell strikes us.

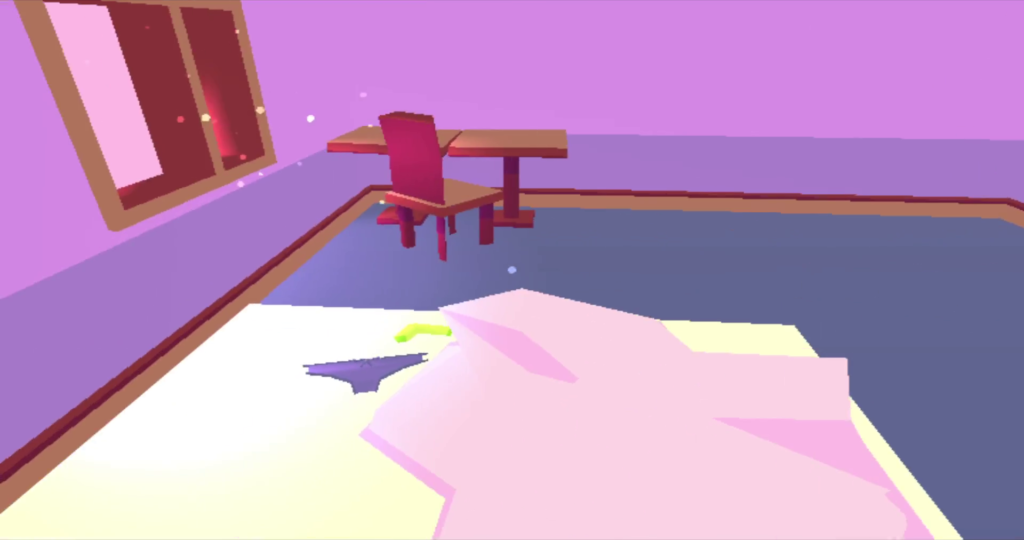

The music, by Ryan Roth, then shifts from generic action soundtrack to a more comforting piano piece. The player wakes up in a bed, sunlight shining clear through the window illuminating the motes of dust in the air. The sheets are messy, and the presence of an extra pillow and some articles of underwear (panties and a sock) suggest an intimate relationship.

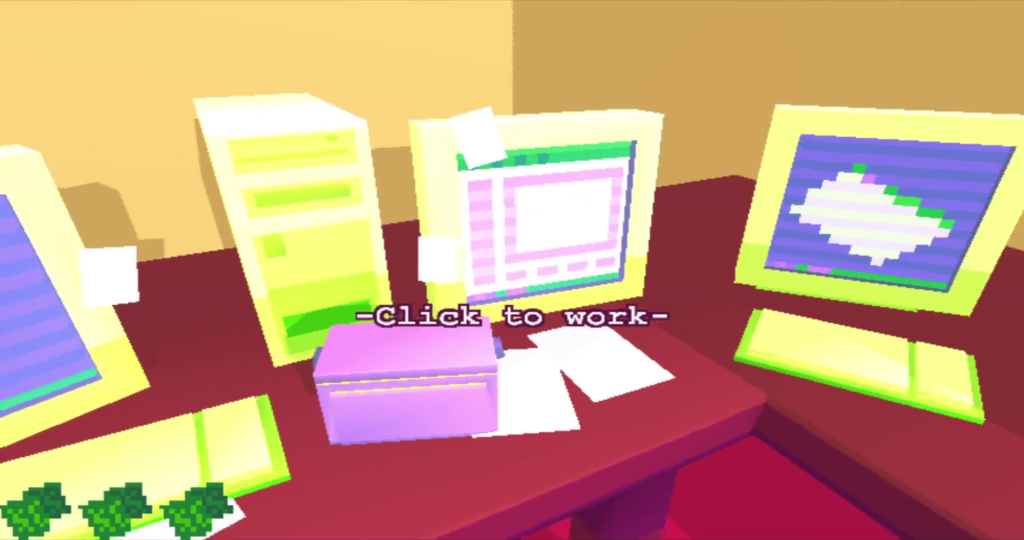

In the next room, we find Mackenzie as our wife (girlfriend? partner? boyfriend?) waiting for us at the kitchen table with a plate of sunny-side up eggs before we head to the office. Whether or not the war is over, we are out of commission but have recovered from our injuries. Then we eat the eggs, talk to Mackenzie, and go to work. Our job is unclear but is performed on three desktop monitors in a small room with a bulletin board.

The gameplay continues to use the same controls as the opening FPS segment. Rather than firing the assault rifle, however, a click simulates every interaction of daily life: turning off the alarm clock, eating breakfast, talking to Mackenzie, and doing a job. Once each computer in the office is clicked, raising a money meter on the bottom of the screen, we head out, have the day’s expenses subtracted from our earnings, and repeat. The only other stat is Mackenzie’s mood, represented by a smiley face beside her, which can be refilled daily by interacting with her. She also sometimes gives us extra cash.

However, beginning on the second day, the generic combat music from the FPS segment sometimes spills over into our present life, and the assault rifle reappears in our invisible hand. It will not disappear until it is fired at least a few times—and clicking is the one way to interact, so we must discharge some rounds. Hitting any object reduces its stylized colors to grayscale and permanently removes it from the environment. Shooting Mackenzie results in the same.

Losing tables and kitchen cabinets leaves our apartment more barren, suggesting poverty. Losing desktop monitors at work affects our income. As the days move on, the episodes of the metaphorical gun occur with increasing frequency. I tried playing smart, shooting into the ceiling or walls instead of objects, clicking carefully so as not to gun down dear Mackenzie instead of talking to her but did not reach ten days.

Frail Shells will force the player at least to shoot the computers and destroy our ability to earn money, which leads to Mackenzie leaving us. Though the bedclothes and green sock vanish, the panties remain. Are the panties a surprisingly sexual memento? I don’t think they belong to the disembodied player character because then we would be wearing them. Or is Mackenzie a boy? That gender ambiguity is good, allowing for more universal player projection into the protagonist’s situation.

After this, the piano music, no longer comforting but rather quietly sad, continues the same as ever while the credits roll. The player can keep playing, but instead of looping through the whole day, a version of the opening plays out in which we have no visible health meter and no gun with which to fight back against the enemies. Upon reaching Mackenzie or being gunned down, we reawaken from the nightmare in the empty bed, remarking on how many days have passed. Upon stepping outside, without any company and without any breakfast, the credits play again, looping back to the nightmare. This ending is unsatisfying, concealing whether more video game remains. If I keep playing long enough, would something else happen? Could I patch things up with Mackenzie? Probably not. This uncertainty is not a design flaw but an intended emotional response. The character’s life does not end. The character does not know what tomorrow will bring, only that tomorrow will continue to be boring, painful, and empty. And so the player is left in an analogous mental state.

Bullets and bombs perhaps come in frail shells, as the title suggests, but our bodies are frail shells as well, both in their physical weakness to the shells that injure us in the action segment and in the psychological repercussions with which those injuries devastate us even after physical convalescence.

In its few minutes of playtime, Frail Shells delivers no particularly unique or groundbreaking message. But, in the world of video games, where even thoughtless, incoherent attempts to say anything often generate critical praise, the tight vision of Frail Shells is laudable. From Smiling delivers this parable efficiently with all the subtlety of a bullet to the body. Some people might consider this lack of subtlety and complexity childish, but I am the rare person who tends to enjoy overt didacticism when crafted well and delivered without pretension.

So far I have avoided the most significant aspect of Frail Shells. The simulation of daily life is shallow, reducing interpersonal connection to clicking the mouse, Frail Shells is not a detailed simulation of marriage and work life. But while there are a few syllables of dialogue from Mackenzie and, on black screens between each day, the player character, the point of Frail Shells is to convey a story through that feature unique to video games: interactivity. The gameplay itself, in combination with the aesthetics of a happy partner and a nice apartment and then their dissolution, tells the story. The ostensive action hero war simulation we expect by video game conventions falls away, our disappointment presumably mirroring that of a character who expected glory but got gruesome defeat. In the “real world” that awaits afterwards, the need to earn a wage and to show affection to our partner strikes a happy, peaceful balance more fulfilling than the shallow violent gameplay that came before, but PTSD wrecks this comfortable life, the approach essential to the battlefield reappearing in a context where its is unhealthy and maladaptive, leaving us broke in an empty apartment with, for the player on the real-world side of the screen, no more video game to enjoy. Though the narrative subversion of a power fantasy, while successful, might not stand out, the gameplay subversion achieves what almost no video game does. In Frail Shells, From Smiling, instead of awkwardly wedging a story between gameplay, tells a story with the gameplay.

From Smiling has released increasingly few video games after 2014, perhaps from financial constraints, considering the Frail Shells itch.io page pleads for money with a crying emoticon and the dev’s parody of alienated labor, Job Lozenge, that came out the month after Frail Shells. However, Bai-Woo seems to remain active as part of GLOAM, a collective developing the RPG Bravery Network Online. From Smiling as such might be over. Though less than ten minutes long, Frail Shells is a worthy legacy, then, a rare example of complete integration of gameplay and story, a model of the possibilities of the digital medium we would be wise not to forget.

…Is how I would have ended this post were it not for an additional piece of information.

The serious tone of Frail Shells is unusual for From Smiling, falling outside the wacky comedy characteristic of the rest of the developer’s output. In its bluntness, graphical crudeness, and brevity, Frail Shells seems more like an opening salvo for an up-and-coming developer’s career than a tonal and thematic one-off. Why didn’t From Smiling pursue digital narrative experiments into areas of greater nuance and sophistication? Because, while everyone on the internet, from published critics to YouTube comments, interprets Frail Shells as a portrayal of PTSD, Bai-Woo did not intend this message!

For an article in The Boston Globe, Jesse Singal (I think, unfortunately, that Jesse Singal?!) emailed Bai-Woo about the story of Frail Shells and received this response: “I definitely didn’t make ‘Frail Shells’ as being something about PTSD though, [sic] it can easily come off that way because it might seem like that’s literally what’s going on.” Apparently, Frail Shells is meant as a joke based on the notion that FPS games only allow interaction by shooting. Wouldn’t it be goofy and sad if, in a video game about daily life, sometimes the main interact button fired a gun instead? “I’m not super comfortable of [sic] people thinking the game is about PTSD mostly because I don’t have PTSD or know anyone that has it.” Bai-Woo’s email pulls down the curtain to reveal the reality that most players, including me, have no experience with PTSD and are basing their reading off pop cultural depictions of this illness. Where do I get off pretending I know what PTSD is like?

This might recontextualize the silly action movie tone of the opening, Mackenzie’s absurd body count and the enemies hurtling away like pieces of paper not just genre subversion but genre parody. Perhaps Frail Shells is really a commentary on how all first-person video games originate from violent shooters and a criticism of the crass brainlessness of the many video games that send a disembodied camera with a gun in front of it to murder everything. This theme, for its novelty, would be more intriguing, if less political. But, more than anything, Bai-Woo’s email leaves me confounded—how could someone create a focused metaphor welding theme to medium with rare skill and poignancy by accident?