Published 6 May 2022

One of my favorite developers is Owch, a pseudonym of “arcanist” Chloe Taylor, creator of numerous challenging video games of varied genre but a consistent minimalist aesthetic, dark tone, and recurring symbology. Of these, the least cryptic is PALACE OF WOE, a 2019 “sort-em-up labyrinth” available on itch.io.

As with all of Owch’s video games, the story in PALACE OF WOE is more the player figuring out what to do than a conventional plot, so if you would prefer to play a delightful puzzle game “unspoiled,” click the link above and drop a few dollars to play it. Or download it right now if you bought the itch.io Bundle for Racial Justice and Equality or the Bundle for Ukraine.

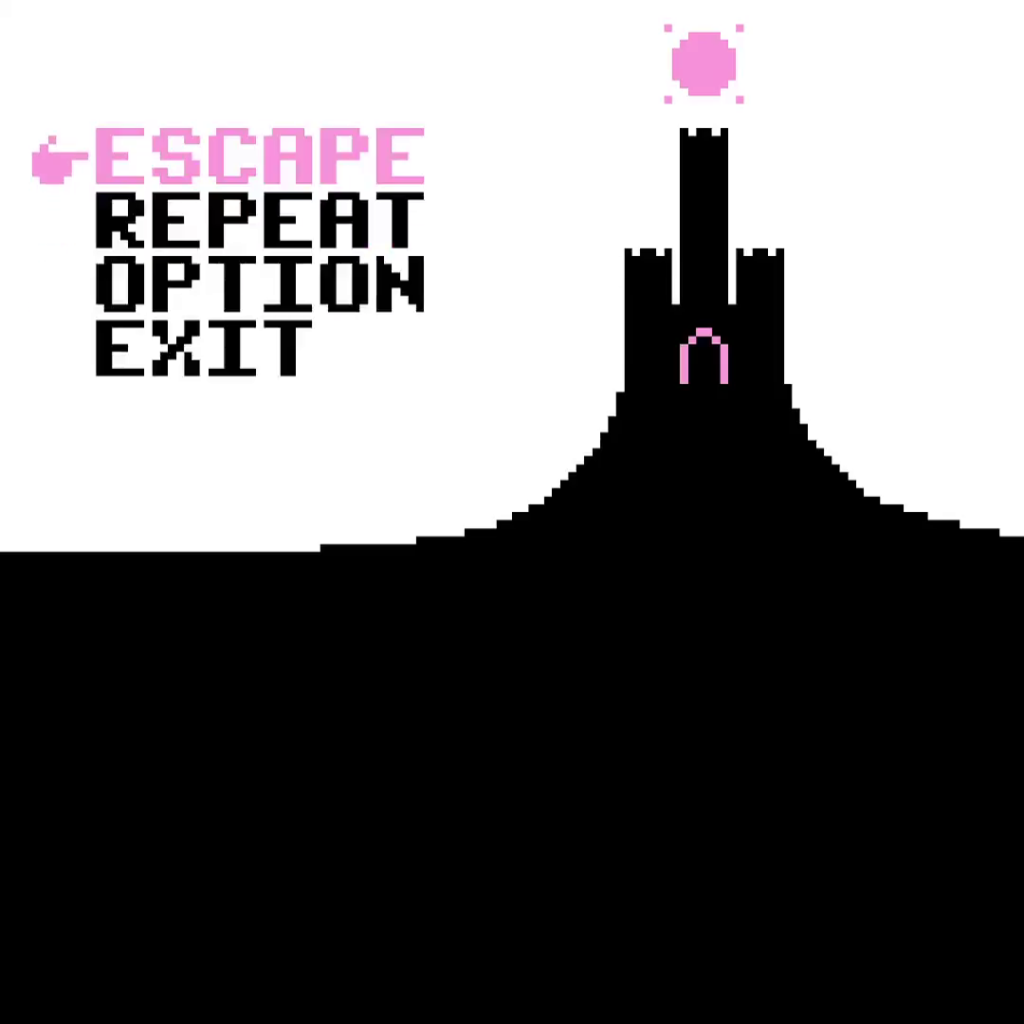

Per Owch tradition, PALACE OF WOE dumps the player into an eerie, supernatural world with zero exposition or instruction. The window of the game executable is entitled “LOOK at the PALACE OF WOE,” and instead of “Start” or another conventional option, the title screen begins the adventure when the player selects “ESCAPE.” A clear mission statement: ESCAPE the PALACE OF WOE.

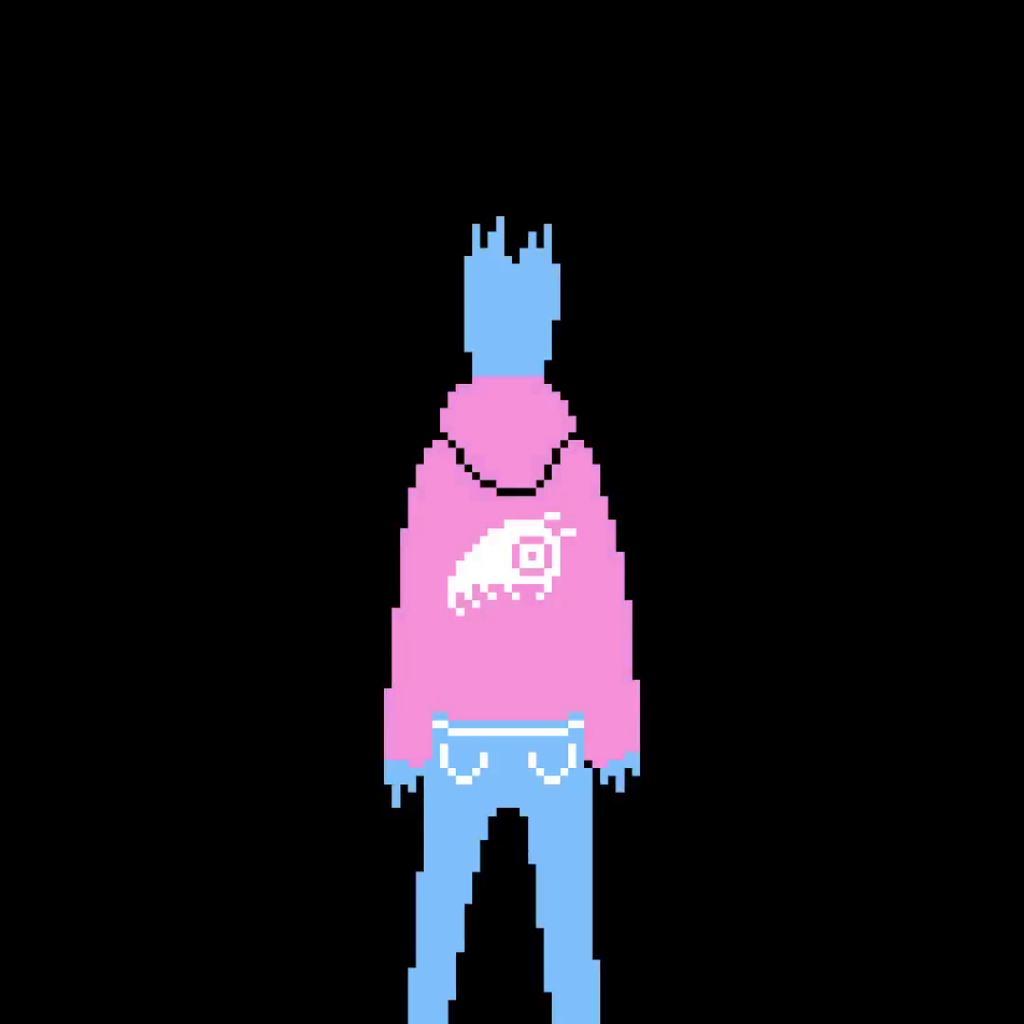

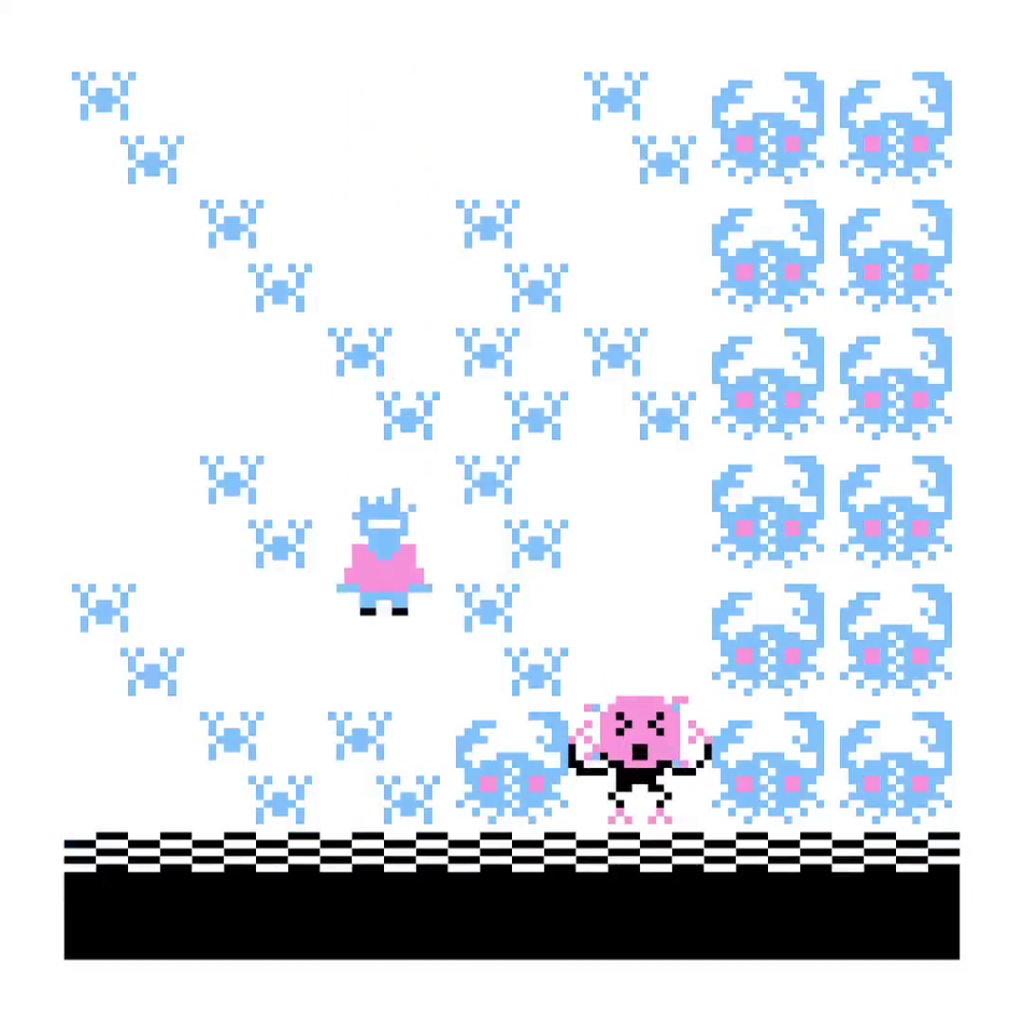

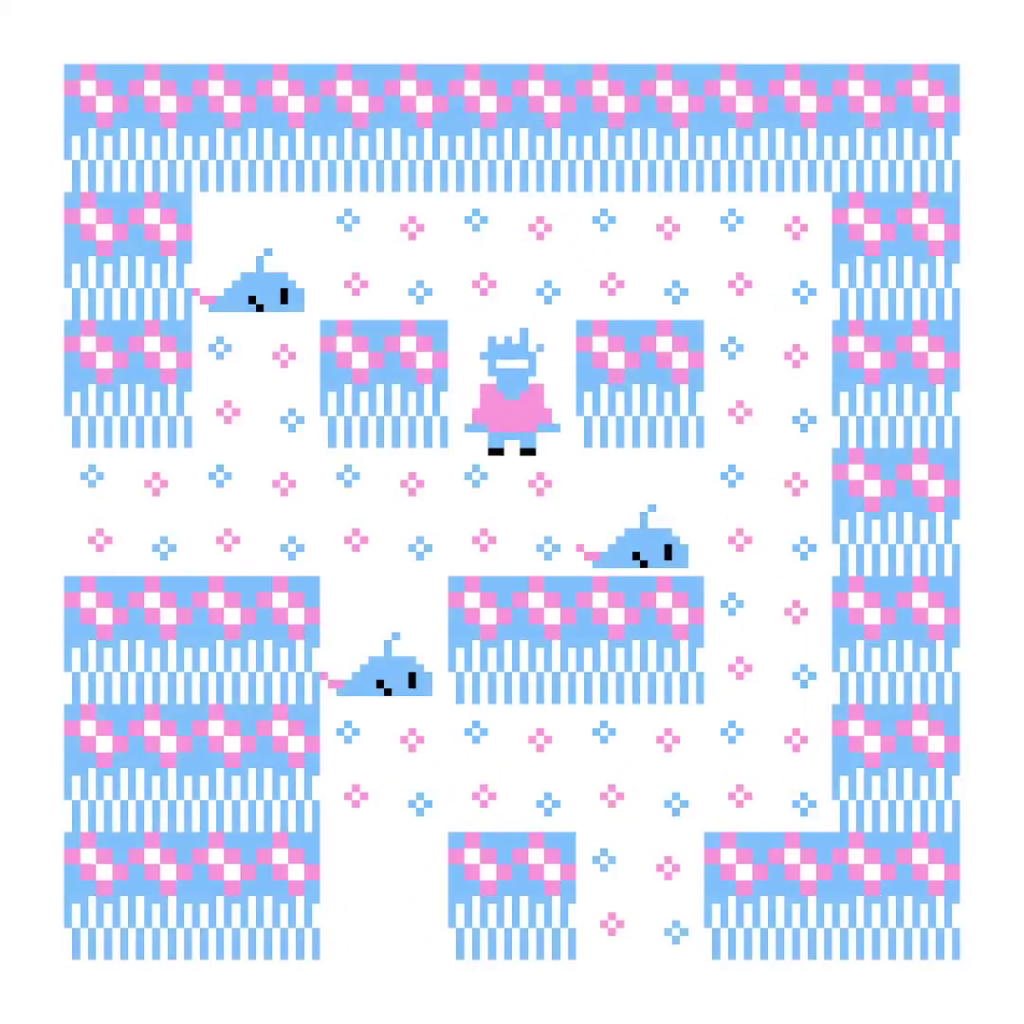

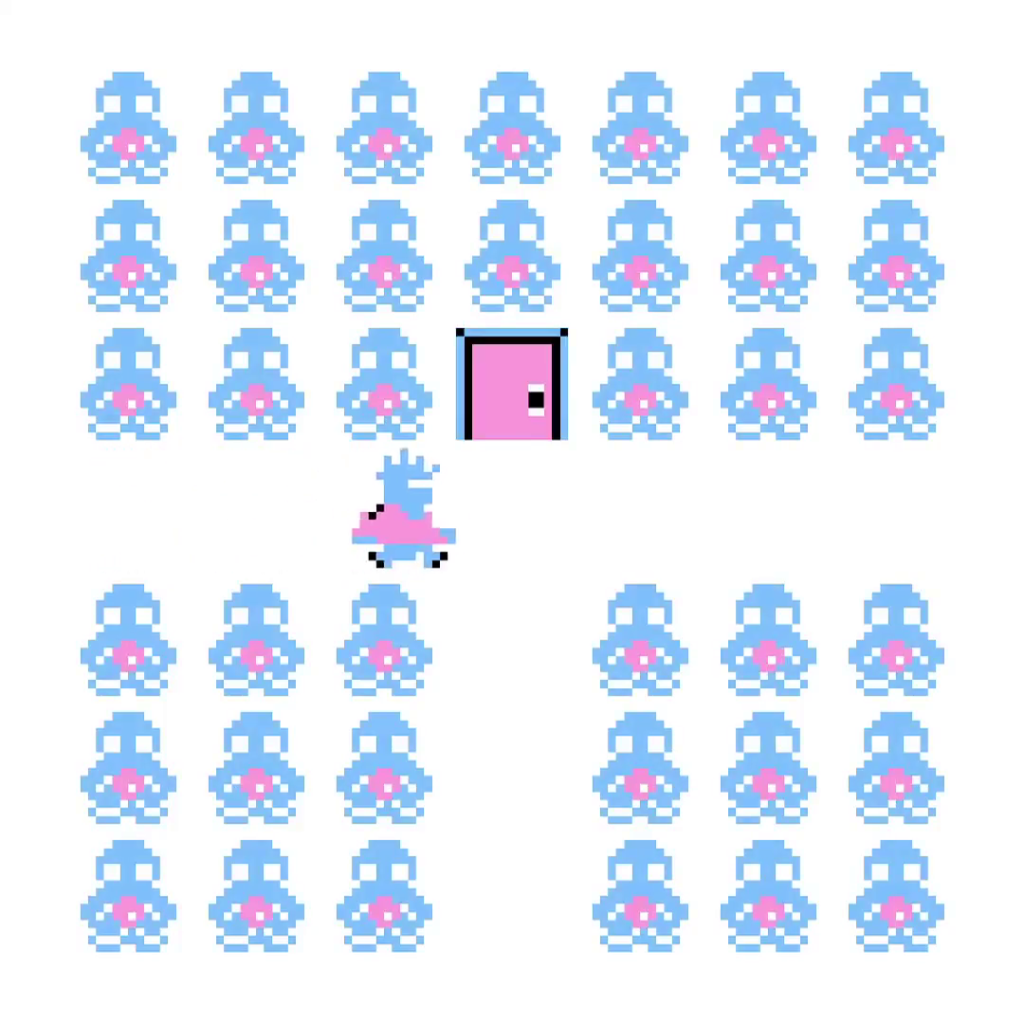

From a top-down perspective and an aspect ratio suggestive of the Game Boy, the player controls a spiky-haired character in a hoodie, the back of which is emblazoned with a bug-like shape. As the first room forces the player to learn, this one-eyed tough can kick chairs, trees, coffins, and any other object Sokoban-style to clear rows of obstacles. Rather than scrolling, movement occurs on a screen-by-screen basis. Leaving a screen resets every obstacle and every enemy. Only bosses, rare unique encounters such as possible Beat the Art Breaker nod Sink (who knows the secret) or Chloe herself, do not respawn.

In PALACE OF WOE, enemies and bosses are also more akin to obstacles, neither moving nor provoking combat. The majority not obstructing essential passages can be safely ignored. There is no gameplay benefit, such as EXP or money, to be derived from “fighting” each foe beyond the literal experience of practice.

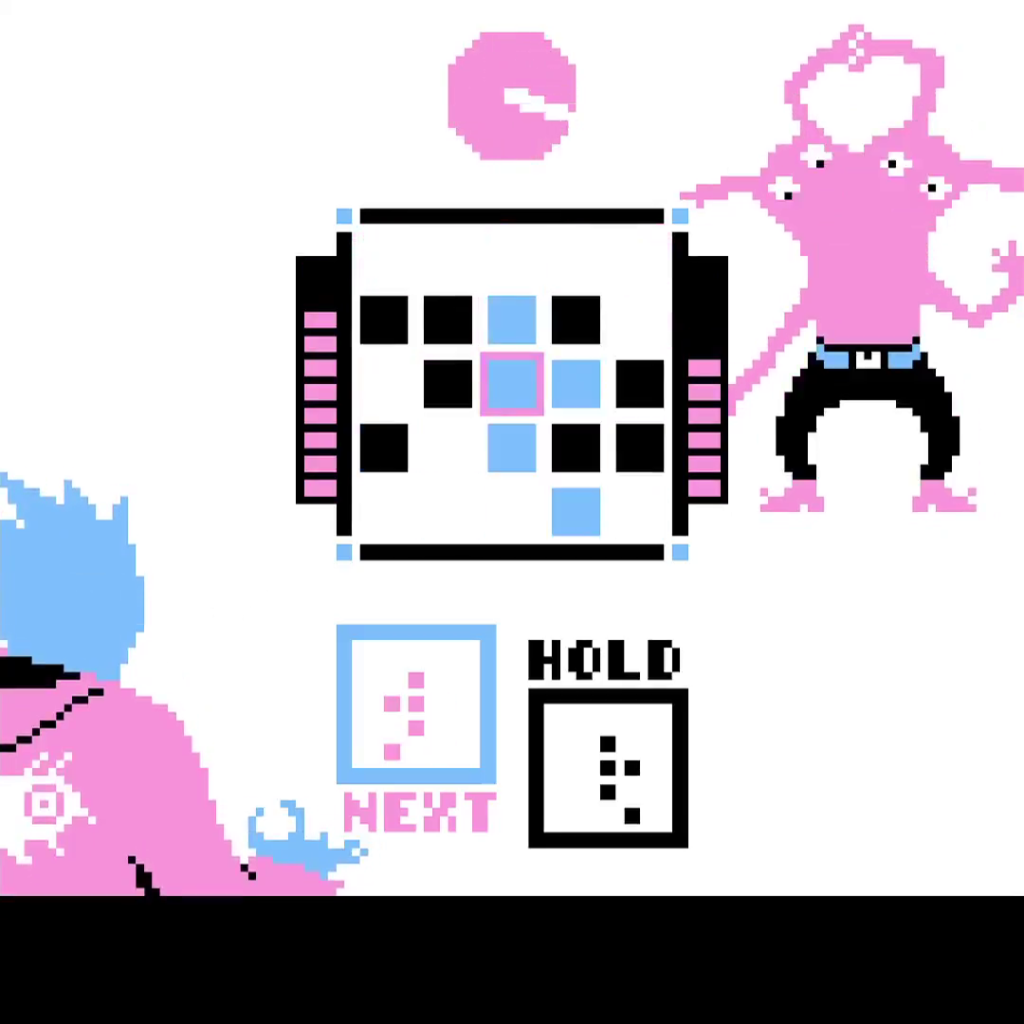

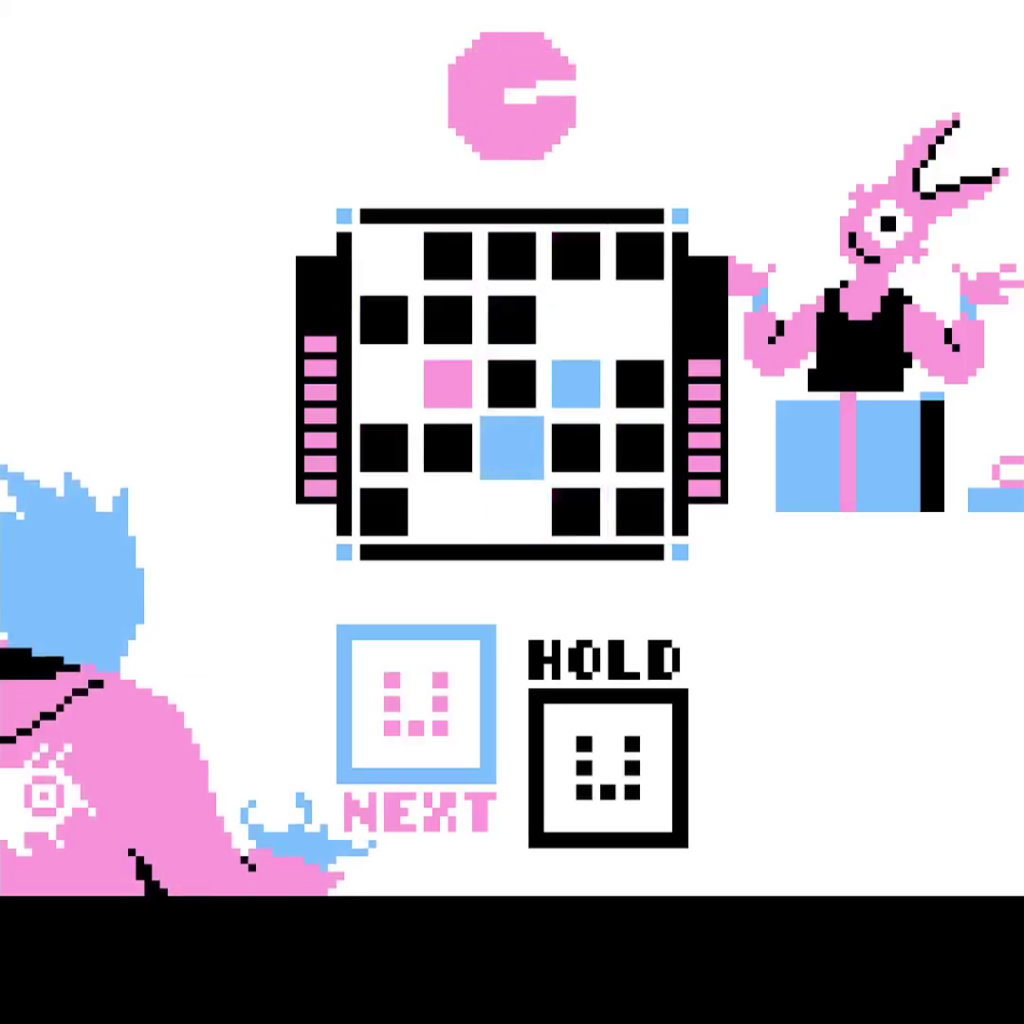

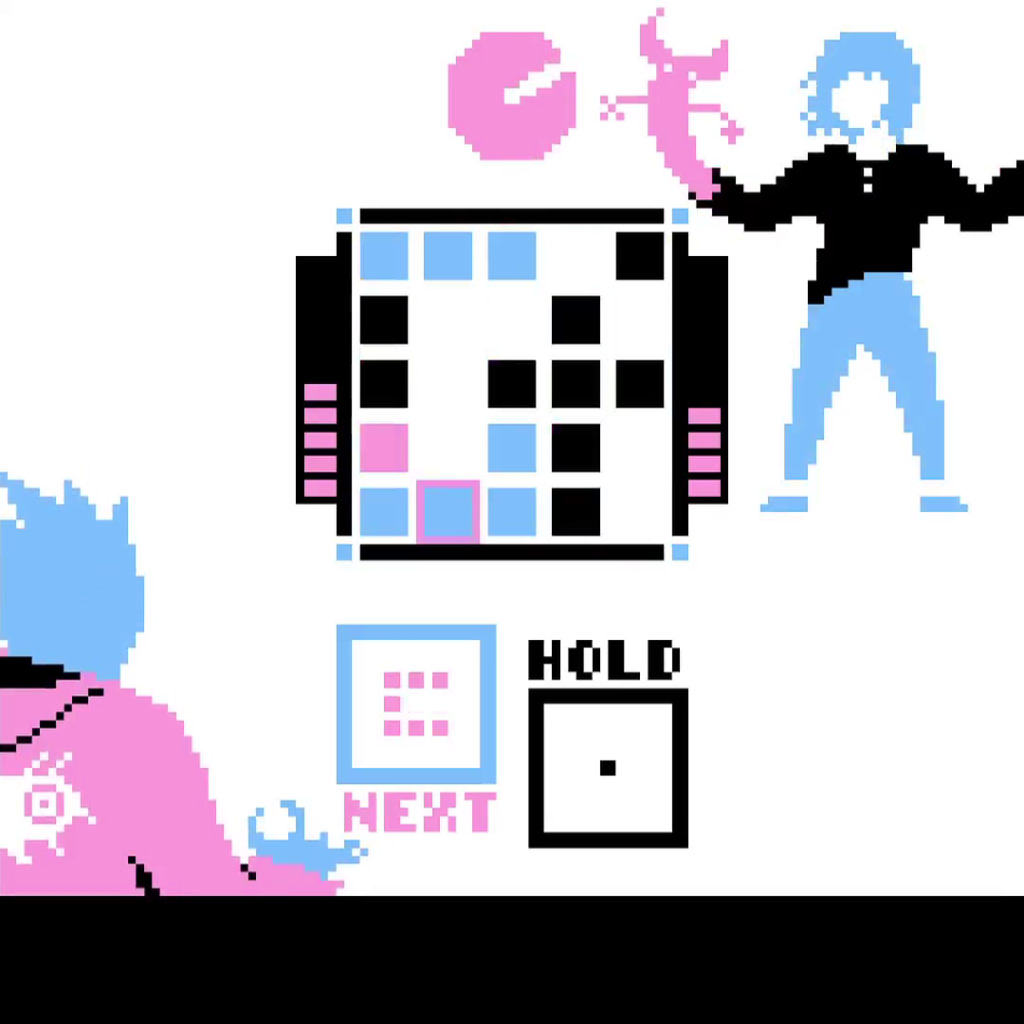

The enemy, often something cute in the overworld but more disturbing up close, is angled to the spiky-haired protagonist like an opponent’s Pokémon. Brief flavor text and ominous, raspy droning (probably the battle theme slowed down) introduce our opponent: “LONGLEGS is hungry.” The action occurs in a box in the middle of the screen. On the right of this box is the player’s health bar, and on the left the opponent’s. Clusters of square tiles in different arrangements appear in the box, which can accommodate a five-by-five grid of these tiles and whose edges wrap in on themselves. The player must place the set of tiles before a time limit indicated at the top of the screen places the tiles for us. If a full row or column of the box is filled, this row or column of tiles vanishes, and the enemy takes one HP damage. However, if tiles overlap other squares already set into the box, these tiles vanish, each one lost sapping one HP from the player character. The “combat” system is splendid, simple in concept but allowing challenging permutations. Each enemy demands the player manage different tile layouts, many large and ungainly. The toughest enemy, Gutrot, I even thought impossible to beat until I saw a let’s play in which the player, Alex Diener, defeats one with no difficulty.

There is also a hold box that contains a single square tile. Once per battle, the player can swap the larger set of incoming tiles for this single one and a hopefully easier, lifesaving move. While this seems like an emergency measure, it is strategically valuable and proves essential for Gutrot and Look. The main menu also allows the player to fight enemies context-free to optimize our skills and maximize efficiency, a sure draw to those who thirst for mastery. The difficulty level is inconsistent, however. I struggled with Badmouth, a standard enemy, more than almost any of the bosses.

If defeating enemies is not the objective, though, how does one escape the Palace of Woe? The answer is simply to find the Exit. Guarding it, however, is an amorphous glitch-entity, Swim, who appears throughout the Palace to tantalize the player from unreachable areas.

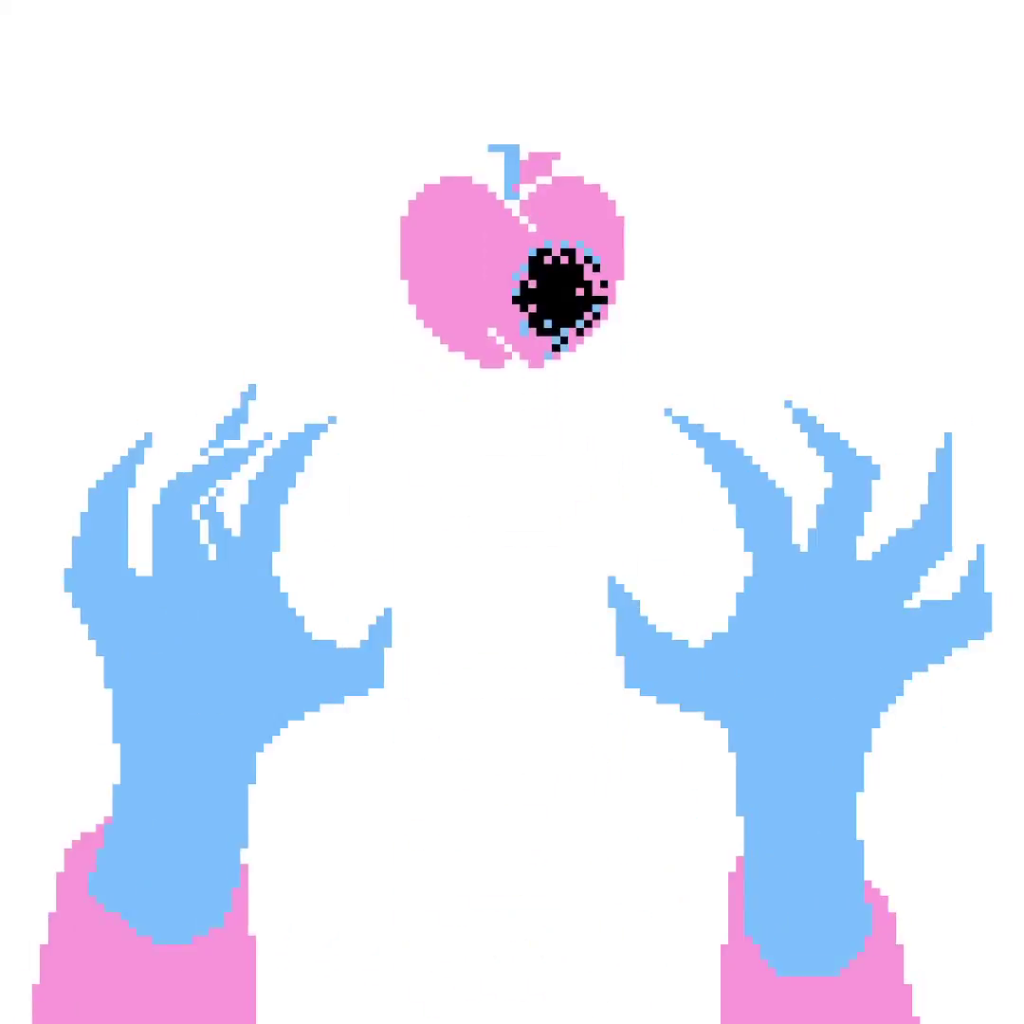

To transmute Swim from a swarm of pixels to a solid being, the player must locate the twelve “keys” and then her lair behind several screens of pills. Not “keys” in a typical sense, these arcane miscellanea allude to other Owch games, such as an apple with a hole in it that might have been held by the player character’s blue neighbor in Long Live the Axe. PALACE OF WOE follows the time-honored video game collection structure.

The music loops, also by Owch, are short and usually spooky. After all, the Palace of Woe is not a place one wants to be. Most of the battle themes—“BOOT,” the four “DARKPUSHER” tracks, and the “boss theme”—while still ethereal, are surprisingly soothing and upbeat, music not for life-or-death struggles but for progress. “Don’t give up!” they seem to say, welcome encouragement on my fifth try against the same tree.

The environments that the overworld Sokoban rooms constitute, rendered in tile-by-tile pixel minimalism, portray recognizable though abstracted spaces. The player begins inside a ghost-filled building, presumably the Palace of Woe itself. However, most of the map consists of this prison’s environs: shorelines, a graveyard, and apple tree forests. The northern reaches of the map, areas such as those the soundtrack identifies as hermit haus and ticks inn, plunge into surreality unrecognizable as physical places. For none of the Palace of Woe is a physical place, being instead, like the enemies encountered in it, representations of the hero’s psychology.

In PALACE OF WOE’s short length, Owch fully explores the game systems and achieves a work satisfying and unified in form and theme. Not only a compelling and fast-paced puzzle system, the “combat” frequently means accepting damage of our own, suggesting a dissociation between self and body. That overworld navigation and combat both revolve around different forms of “sorting” also plays into “sorting yourself out,” the central theme. Characters similar to the PALACE OF WOE player character appear in Owch’s earlier Beat the Art Breaker and Long Live the Axe, where their humanoid forms serve as modifiable avatars for pink bug-like beings resembling the creature on the PALACE OF WOE protagonist’s hoodie. The suggestion of minds capable of moving between different bodies here serves an explicit transgender metaphor. PALACE OF WOE is a model of brevity, completeness, and thematic coherency.

This spiky-haired tough is not so brutal as Owch’s previous bruisers, with whom she shares voice samples. Rather than dying or exploding into blood, her enemies, when trounced, merely “[step] aside” to let the player continue. This and the framing of the protagonist’s situation as escaping a prison instead of invading someone else’s territory make for a less morally ambiguous story. Where 10S reaches a degree of difficulty that borders on the humanly impossible, PALACE OF WOE’s forgiving loss states drop the player back to the start of the screen. Instead of the limited checkpoint systems typical of Owch, PALACE OF WOE generously saves on every screen.

To miss the blunt but affirming allegory that the ending of PALACE OF WOE spells out would demand superhuman pigheadedness. It is not a coincidence that the default palette (except the black) matches the colors of the transgender flag. In contrast, exegesis of other Owch titles, like Long Live the Axe, is beyond me.

The cumulative result is something that, by Owch standards, feels kind and clear, more accessible. This (presumable) wider audience appeal suits what, despite first appearances, is a hopeful albeit simple message for those who need to escape the Palace of Woe in real life. However, the other manner in which PALACE OF WOE proves accessible is no different from the rest of Owch’s portfolio: complete excellence.

Check out this and other arcana from Owch at her itch.io page.