Published 25 July 2022

In a trademark bewildering move, Nintendo recently added this all-star lineup to Nintendo Switch Online: Kirby’s Avalanche, a 1995 Western-exclusive version of Super Puyo Puyo reskinnned with Kirby characters because a video game starring a wacky little girl would have overwhelmed delicate non-Japanese audiences; the Super NES port of Fighter’s History, an arcade fighting game from Data East released in 1993; and…Daiva Story 6: Imperial of Nirsartia, released on Famicom in 1986??? When you think they will zig, Nintendo do not zag—they zoog.

Daiva Story 6 is an experimental title from T&E Soft (former employees have alleged that what “T&E” stood for changed routinely). The clunky subtitle “Imperial of Nirsartia” is derived from the English-language title screen, but the box art gives the title as “ナーサティアの玉座,” “Throne of Nirsartia.” The player controls pirate captain Matari Shuban (マータリ・シュバン), directing a spaceship to attack different planets of the Empire in a rudimentary strategy game. Combat on each planet’s surface takes the form of similarly rudimentary sidescrolling shoot-’em-up levels. Apparently the player’s goal is to conquer the Death Star-esque weapon planet Vitra and the titular Nirsartia to, I assume, become the new emperor by sitting upon the Throne of Nirsartia.

The story is minimal, the ending just a credit roll. However, the title Daiva Story 6 raises questions. What is Daiva Story? Where are the other installments? This is part of why Nintendo’s decision to release Daiva Story 6 surprised me. As readers may be aware, I am something of a Famicom aficionado, so I recognized the title Imperial of Nirsartia instantly.

Outside of Japan, T&E Soft suffers from an unfairly bad reputation for Naito Tokihiro’s Hydlide series of fantasy action RPGs, which are actually quite innovative and intriguing. The original 1984 Hydlide seems so crude only because it was a trailblazer, walking so that The Legend of Zelda could fly. Daiva Story 6 would seem to do nothing to challenge the low estimation of T&E Soft. But this is because, in isolation, its creators’ ambitions lay hidden.

The brain child of Yoshikawa Yasuo, the Daiva series came out in seven parts. There is scant documentation or footage of Daiva on the English-language internet, Daiva Story 6 only somewhat higher profile because of the comparative popularity of the Famicom/NES emulation scene. Most of my information about this mysterious series comes from The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Volume 2 by John Szczepaniak (a book that opens with a bizarre and pretentious rant calling people who don’t like Killer Is Dead or Senran Kagura or the character designs in Dragon’s Crown “social media degenerates” and “human flotsam” 🤨). Supplementing the information from The Untold History are details from the store page of the Daiva Chronicle compilation I mention below.

The seven-part Daiva series came out over about a year. Daiva Story 6, which T&E had to release through a different publisher, Toshiba EMI, came out in 1986. Story 1 through Story 5 came out in 1987 and Story 7 in 1988. Yoshikawa’s bold idea was to release different installments of an overarching space opera all at once, each on a different system and each designed to play to its given system’s strengths. Thus the simulation and combat of the Famicom Story 6 are simpler and more arcade-like than the home computer Stories. The series consists of the following:

Daiva Story 1: Flames of Vritra (ヴリトラの炎) for PC-88, starring Rushana Patti (ルシャナ・パティー)

Daiva Story 2: Memory in Durga (ドゥルガーの記憶) for FM-77AV, starring Ah Mitābha (ア・ミターバ)

Daiva Story 3: Trial of Nirvana (ニルヴァーナの試練) on Sharp X1, starring Amogha Siddhi (アモーガ・シッディ)

Daiva Story 4: Asura’s Blood Flow (アスラの血流) on MSX, starring Ratna Sambha (ラトナ・サンバ)

Daiva Story 5: The Cup of Soma (ソーマの杯) on MSX2, starring Aksho Bhya (アクショー・ビア)

Daiva Story 6: Imperial of Nirsartia (ナーサティアの玉座) on Famicom, starring Matari Shuban (マータリ・シュバン)

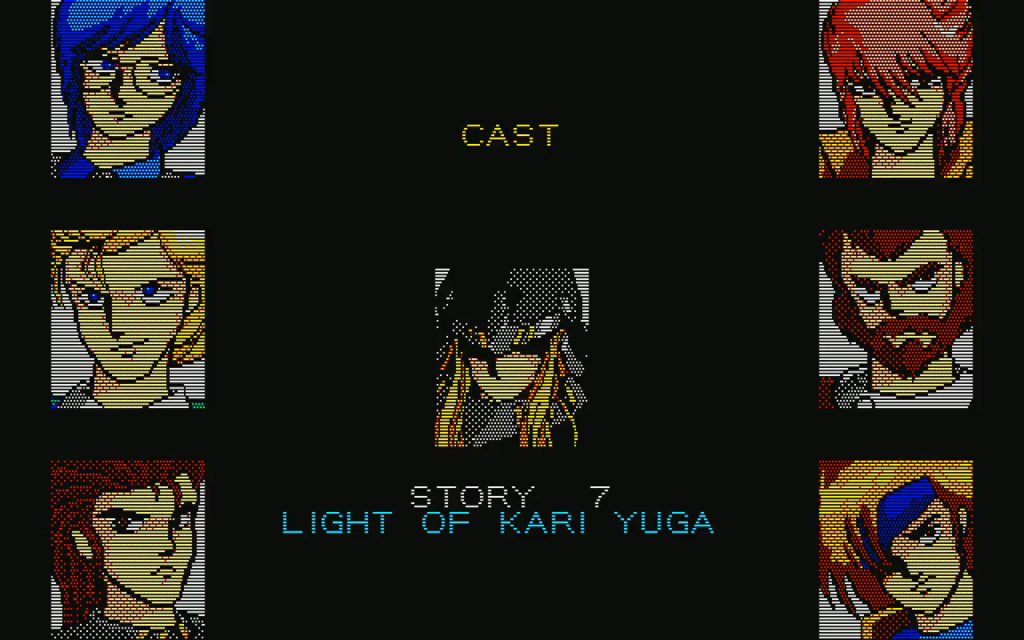

Daiva Story 7: Light of Kali Yuga (カリ・ユガの光輝) on PC-9801, starring Krishna Shark (クリシュナ・シャーク)

T&E billed Daiva as “Active Simulation War.” Most installments involve a combination of resource management, strategic combat, and action stages in which the player character pilots a mecha to attack the enemy planet’s surface. Each chapter of Daiva is a unique video game with a distinct scenario and player character, not a port or conversion. An individual would not have been able to play every Daiva game because almost nobody would own every system, so players, Yoshikawa hoped, would socialize to put together the whole story and compare and appreciate the differences. Further encouraging collaboration, each Story features passwords that can be used in other installments of the series to unlock different ships. Yoshikawa told Szczepaniak, “So whereas normally gamers argue about whose computer or console system is the best, with Daiva they can help each other out and become friends” (55). The entire series was rereleased as a single compilation in 2003 and more recently as Active Simulation War Daiva Chronicle Re: in 2019.

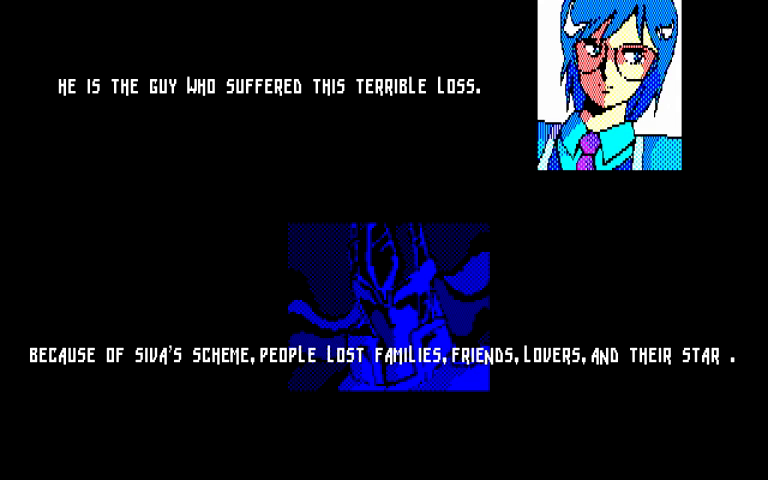

Beyond mythological allusions and references to space empires, I know little of the actual story. Several of the main characters are named after the Five Tathāgatas. The big bad appears to be an Imperial commander named “Siva Rudla” (Shiva Rudra?). Given the shaky transliterations, I am unsure if the Vritra the player apparently battles in Story 1: Flames of Vritra is the same thing as the Vitra of Story 6. Szczepaniak indicates that the different Stories offer different perspectives of the same narrative. However, Yoshikawa originally intended the series to be in five parts, management only later insisting on Famicom and PC-98 chapters. Since Szczepaniak reports that every Story except for these final two features the same galactic map, I am not certain how their plots might connect to the other ones. As with the worldbuilding and artwork of Valkyrie no Bōken, I get the impression the enthusiastic creators of Daiva envisioned a space opera more detailed and complex than what a set of 1987 strategy games could reasonably have delivered and that the existing story is its remnants. Or I am giving a gimmicky series too much credit. Except for the Famicom and PC-98 oddballs, each Story features an almost identical intro cutscene. A Daiva fansite, daiva.info, may hold more lore for those better at Japanese than I. The character artwork in this post comes from this website.

A single T&E programmer worked on each installment of Daiva, all seven (or eight?) people working simultaneously. Yoshikawa reports that he programmed the tactical segments of all the first five Stories, whereas the person responsible for each one programmed the action segment, and that other people were involved in Story 6 and Story 7. Yoshikawa worked so hard for so long that he went blind for several days! Grueling, unacceptable, but also astonishing, the pain that undergirds video games.

I am aware of no other video game series with a similar cross-platform concept before or since Daiva. From the diversification of the market and most especially the increased complexity of video game development, today a project like Daiva would probably be impossible. Unlike the vast ocean into which Hydlide flows, Daiva might be a design dead end, not inspiring imitators. But this series’ existence testifies to a daring willingness to experiment on the part of the programmers and management at T&E Soft—and to their hard work. Daiva Story 6 deserves better than being a punchline in another disappointing lineup of retro titles from Nintendo. This Famicom obscurity warrants respect in a context stripped from it. If the English-language world is to receive Daiva Story 6, we should also get the full Daiva Chronicle. It is not as if the audience could be any more niche.

Also, maybe Nintendo could simply make their vast library of hundreds of great video games available instead of drip-feeding random stuff like Daiva Story 6.