Published 15 August 2022

Content warning for possibly unpleasant sexual subjects.

What Is This

This essay contains sexually explicit images and subject matter. If you are a minor, then stop reading this page. There are plenty of others on this site you can read if you want. If you keep going, then you are indicating both you are a legal adult and prepared to see and read sexually explicit material. (Not that this article is pornography. But it is about something that contains pornography, and I do not shy away from acknowledging, discusisng, and showing screenshots for illustrative purposes.)

In 1996, Elf published the original PC-98 release of YU-NO: A Girl Who Chants Love at the Bound of This World, written by Kanno Hiroyuki, revolutionizing “visual novels.” Through its impressive scale and long playtime, YU-NO set expectations of scope and narrative complexity later titles would emulate, or so many sources allege. Mages published an HD remake of YU-NO in 2017, releasing it in English in 2019. This review, however, regards the extraordinary 2011 fan translation by TLWiki, though it is not a review of the translation itself (aside from one decision regarding the graphics). Not “merely” a translation of a lengthy script, the patch transforms the lackluster 2000 Windows port into a version of YU-NO perhaps more definitive than any other, including the full voice acting from and scenes then exclusive to the Sega Saturn release, the uncensored graphics and script of the PC-98 original, and high-quality versions of Umemoto Ryu’s enchanting FM soundtrack. Please take nothing I say to belittle TLWiki’s outstanding effort, one which seems to have vanished from the internet with the emergence of the Mages remake and its graphics bland as stock photography.

Some writeups of YU-NO shower the multiple-award-winning title with cringing adoration as a moving masterpiece and one of the finest video games ever created. I sometimes wonder if I came from an alternate universe, much like happens in YU-NO, where the version of YU-NO I played is a different beast than the one, in an embarrassing Hardcore Gaming 101 article, Audun Sorlie touts as “a true masterpiece” that “remains just as revolutionary as it did in 1996” “not soon to be forgotten or surpassed.” However, the evidence of other people’s gameplay footage, as well as the principle of uniformitarianism, assure me I played the same video game.

I prefer to avoid writing material as negative as what follows. However, on my Mackerel Phones YouTube channel, I have often referenced YU-NO, as in the Time Zone video whose ideas appeared in my head while recovering from YU-NO. So it would be valuable to explain these references. My let’s play of YU-NO and my largely comedic 2020 video “Who’s Afraid of Yu-no?” are no longer online. Their legacy is a community guidelines strike on my channel and me opting to delete several unrelated quality videos for fear of them possibly violating YouTube’s capricious content policies. The loss of this material has spurred me to return to YU-NO for this third and, I pray, final time in this review and the analytical essay I have also posted to mackerelphones.com. On this website where only I can decide how much nudity is acceptable, I will speak my piece on YU-NO more at length than in “Who’s Afraid of Yu-no?” After all these years, I will break the curse YU-NO cast on me. Some of my points may be nitpicks that I would forgive and not mention in another video game. But the worship of YU-NO, like an extreme masochist, pulls me aside to tell me I must be bloody and brutal. I have expended considerable time on this review and with the essay, so please share it with anyone you think may find it interesting.

To begin, I will address what almost no other YU-NO writeup or review (!) mentions. Here is some ad copy used for the 2017 remake from a post on noisypixel.net: “YU-NO tells the story of a love that awaits from beyond this world.” That love is a mysterious naked woman who appears in the Prologue, and Takuya’s true love and true, final sexual partner in the true ending. And she is his biological daughter.

Most of YU-NO serves as a setup for the final section, what I will call the Epilogue, a half-pedophiliac parent–child incest romance story. “A love that awaits you from beyond this world”—is whoever wrote that trolling? Prior to that point, YU-NO was sometimes pretty and, despite a pinch of rapiness, a gallon of casual sexism, some poor game design, and other problems hardly shocking for some porn adventure game from the ’90s, largely engaging. But the incestuous finale transforms YU-NO from an intriguing game bearing many unfortunate stamps of its time into the worst trash I ever made the mistake of playing. When I seem to say anything positive about YU-NO below, please keep in mind this caveat.

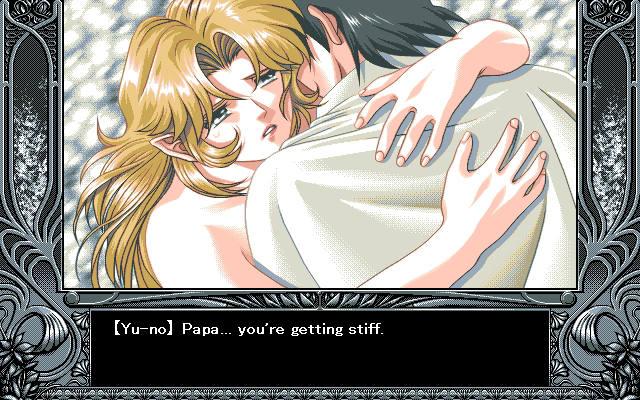

As the credits rolled and I processed these tens of hours of my life, I felt the unhinged Epilogue had come out of nowhere. Sometimes people describe a story as “firing on all cylinders.” YU-NO’s ending fizzles out and dies on all cylinders, casting a pall over what came before. For endings never emerge from nothing. The Prologue opens with player character Arima Takuya remembering his own father considering him a sexual rival for his mother in his infancy (!) and concludes with Takuya making out with his daughter from the future (!). The player then embarks on a quest whose goal turns out to be having sex with their daughter whom the player raises from infancy in-game to really hammer home that, yes, this is your kid and you should really want to bone your kid. The game seems to say, see this actual baby, your actual baby? You’re excited to fuck her later, right? Definitely makes the parenthood storyline read differently when you know that’s how it ends.

This epic-scale tale hailed as enthralling and beautiful concludes with Takuya choosing to abandon the community, friends, and family the player has spent tens of hours getting invested in to instead spend the rest of his life alone at the beginning of time having sex with his vapid shrill-voiced mommy-child-wife with a child’s brain in an adult’s body who just so, so wants to sniff and fuck her dad. Her name? Yu-no.

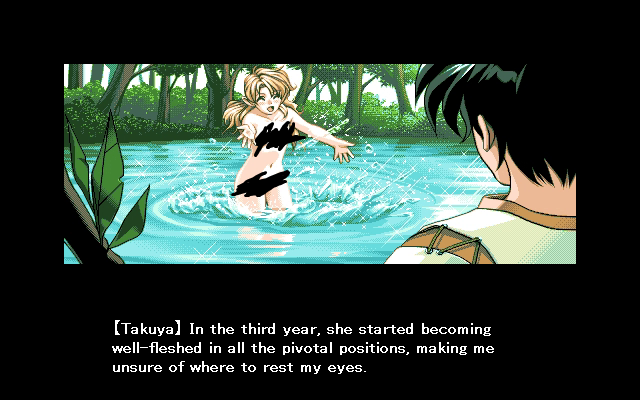

YU-NO, then, may as well be entitled Fuck Your Daughter Quest. This is the ending, the point of YU-NO set out in the very title. You are expected to see that elf child on the cover and think “Whoa, she’s hot.” Player self-insert Takuya says, over an image of full-frontal child nudity, “she started becoming well-fleshed in all the pivotal positions, making me unsure of where to rest my eyes. Even if it’s your own daughter, it’s still a naked girl running around in front of you. It’s hard to just shut down your instincts.”

I hope this isn’t what the reviewer on noisypixel.com meant when the praising the sugary-sweet raise-and-fuck-your-daughter ending route for “having a reasonably shocking twist” (I can think of only one other twist, the Ayumi spit-take I describe below in “The Worst Ending of All Time”). Retroactively, characters asking Takuya what his plans for the future might be or even showing him trust send a chill down one’s spine. When, in the Prologue, his stepmother Ayumi tells Takuya that her wish is “for [him] to walk wholeheartedly on the path [he chooses,]” this path is abandoning the rest of humanity to become his own daughter’s sexual partner. A good writer might craft this scenario as a visceral condemnation of Takuya, or give you a harrowing and intense scenario where characters grapple with their complex and shocking emotions and actions. But, with sappy romantic music and sappier writing, YU-NO depicts this relationship as cute and aspirational. This must be that “revolutionary” quality Sorlie refers to: I can’t think of anything else quite like it!