Published 28 January 2022

In 2018, Polish studios OhNoo! and Smile released the Kickstarter-funded adventure game TSIOQUE, a luxuriously animated and Dragon’s Lair-inspired fantasy story written by Alek Wasilewski told in the medium all great authors strive for, the point-and-click adventure game. It is available on GOG and Steam. With the striking cartoon style of its young hero and the ambiguity of that mysterious title, TSIOQUE caught my attention. What could a “TSIOQUE” be? Unfortunately, the answer was not as exciting as the game’s fans made me hope.

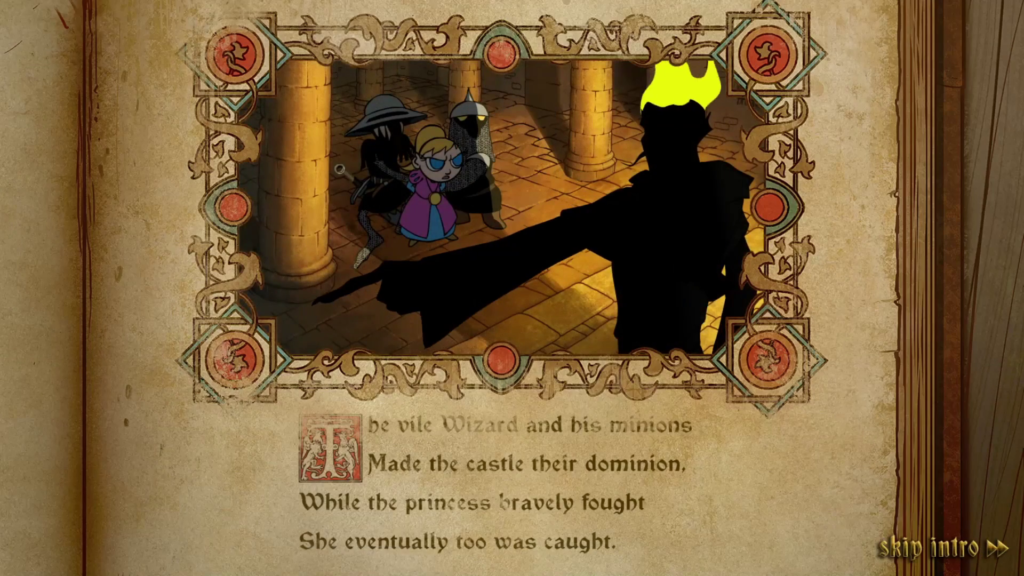

The plot of TSIOQUE is that the Good Queen leaves her kingdom to fight the Phoenix. In her absence, the evil Wizard seizes control of her castle and, with a legion of buffoonish goblin-like monsters, locks the princess Tsioque away. The gameplay begins with Tsioque in a prison cell. Tsioque has had it up to here with the Wizard. She is freaking angry. From this disempowered position, the player must escape, indirectly killing the guard and then several more. This kid’s grouchy expression remains the default from start to finish, but considering the circumstances, she is remarkably well-behaved. Tsioque burns inwardly but, unlike most little kids, never screams or even speaks outside of brief text popups: “Looks like another recipe, like on the other page, but somebody smeared black spots all over the pictures. How can you ruin books like that!” There is little text or speech whatsoever outside the forced rhymes of three segments of narration at the opening, end of the second act, and ending. But Tsioque’s emotive face and actions speak to her crafty, confident, and adventurous personality, as does her missing chunk of right ear, subverting the thoughtless sexism of Dragon Lair’s Princess Daphne.

The marketing insists TSIOQUE is “dark,” but this “darkness” extends little beyond the whole adventure occurring at nighttime. None of Tsioque’s possible defeats are gruesome. While Tsioque kills several of the Wizard’s guards, this is slapstick rather than graphic violence. In the Steam forums, someone named Hastur (the unspeakable!) inquired into whether TSIOQUE is dark like the blood-drenched Fran Bow. It emphatically is not. TSIOQUE is children’s entertainment, at worst very slightly edgy in a PG way. Even the similarly cute, wacky, 2D-animated, kid-friendly “dark” fairytale-themed point-and-click adventure game about a little girl being hunted by an evil (but misunderstood) sorcerer Anna’s Quest is far darker.

TSIOQUE has standard puzzles. Click on things, pick up items, and use items with other items. The main goal in the second segment, for example, is collecting an assortment of random objects, such as a carrot for the long nose, that Tsioque can use to impersonate one of the Wizard’s minions. Although Tsioque can hardly move in the heavy disguise she assembles, I was still annoyed to see her throw it aside so quickly after I had spent the last couple hours trying to make the thing, particularly after the protracted puzzle that involves manipulating training dummies to sabotage a contest between two of the Wizard’s henchmen. While demanding nothing like arcade skills, this particular puzzle is half-puzzle, half-quick time event. This leads me to one of TSIOQUE’s more distinctive features.

OhNoo! and Smile throw in minigames and quick time events. For example, at one point, Tsioque must crush the foot of a guard, the only of the Wizard’s minions depicted primarily as a threat instead of comic relief. He then pursues her down a long staircase. To run and dodge the swings of the goblin’s sword, the player must click circles that appear at random spots on the screen.

The aesthetic aside, it is in these moments that the Dragon’s Lair influence is clear. Never fear, for unlike Dragon’s Lair, Rick Dyer and Don Bluth’s 1983 scheme to mooch quarters in exchange for the pleasure of trial-and-erroring a quick-time-event path through a terrible though well-animated film, TSIOQUE is not punishing. A failure to react in time tosses the player back to the beginning of the action sequence, usually after a loss animation so brief that hopping back to the start disorients. But it is a relief that, also unlike Dragon’s Lair, in defeat Tsioque comes off more “whoops” than distressed—if we saw a little child crying or seriously hurt, that would more than slightly wreck the tone. Somehow watching the alligator-headed fairy swallow Tsioque whole is not disturbing but hilarious.

Though providing gameplay variety, the action sections, most of which occur at the opening, are incongruous with the rest of the experience. It seems to me that point-and-click adventure games appeal to audiences the typical reflex-based video game does not. By including these segments, the developers have not created game systems compelling enough to play for their own sake while also alienating much of that “casual” point-and-click audience. There is a post in the Steam forums by one apena9621 protesting that a disability physically prevents completion of the minigames, rendering TSIOQUE impossible. “SO ANOTHER GAME THAT i [sic] WAS STUPID ENOUGH TO BUY.” Though another person in the thread notes that TSIOQUE allows one to skip the minigames after several failed attempts, I wonder if there is any demographic for underwhelming minigames that disrupt the flow of uninteresting puzzles in a forgettable scenario.

It is clear that I dislike TSIOQUE, but I have yet to mention the strongest mark of the Dragon’s Lair inspiration: the animation. In an age dominated by 3D animation that, no matter how artful, is doomed to look worse than the 2D concept art, TSIOQUE features loving, fluid 2D animation in full HD. The lively animation is TSIOQUE’s greatest strength. The background designs drawn by Michał Urbański and Dagmara Gąska are immaculate, the painterly craft that goes into every screen humbling someone like me who would find drawing simple Tsioque herself a chore.

Even the minor characters’ gestures and expressions reveal a vibrant liveliness. No criticism I level against TSIOQUE belittles the care clearly put into the craft of its visual presentation. I have no desire to deny OhNoo! and Smile the strength of their talent.

But there is a downside: animations cannot be skipped. When Tsioque walks into a room, the player must watch the full animation every single time. TSIOQUE can be completed with minimal backtracking, but while trying to learn what to do without a walkthrough, these repetitious animations rapidly irritate. Seeing a unique animation of this plucky princess refusing to be beat down and climbing the stairs or shying away from a guard can be engaging the first time. But the third time, re-watching Tsioque’s same unskippable moves demoted the production values from lush to annoying.

TSIOQUE has its highlights, like the explosive battle between the Wizard and the alligator-fairy and the entire running gag yet also serious plot point about the Wizard demanding silence. The dragon whose stomach is a prison with bars also stands out as weird and gross. I enjoy, for the sheer incongruity, Tsioque filling up a bottle of Coke with Mentos to distract some people. Yes, Mentos—in the third act, the story takes a shocking turn. Major spoilers from here on out!

Beneath the inky shadow, the Wizard is actually Tsioque’s father, the king. With the horrifying Wizard-King abomination on her tail, Tsioque finally prepares to escape the castle. But—just as Tsioque, astride her zebra steed, leaps over the broken bridge—the Wizard captures her. In a flash of dark magic, the zebra transforms into a toy tumbling down a stairway in an apartment complex.

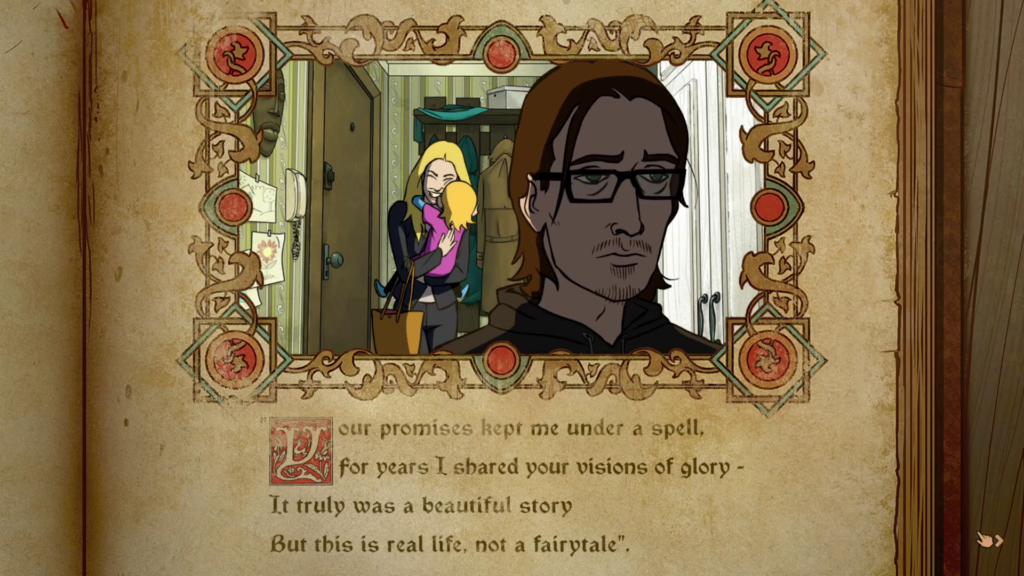

Tsioque is not a princess at all but instead a little girl living in a modern-day apartment with her mother, the Good Queen, and her father, the Wizard. The entire story has been the girl playing make-believe with toys and household objects. This becomes clearer as she runs short on convincing fantasy scenarios, leading to the Coke and Mentos incident, for example, causing racket that bothers her father. The Wizard is an unshaven, hoodie-clad game developer trying to finish a project while his angry, overworked wife slaves away at an office job to actually pay the bills. Returning from work—“[a]nother day’s monster”—the mother, in the bitterest mood she has ever suffered, tells him:

“Your promises kept me under a spell.

For years I shared your visions of glory—

It truly was a beautiful story

But this is real life, not a fairytale.

We’ve no more strength to fight monsters alone.

To daydream we can no longer afford.

It is now your turn to pick up the sword

And take your place on the family throne.”

The dad insists that his dream project is almost finished. The ending is the girl becoming annoyed her parents aren’t paying attention to her. Given the father’s glance at the “camera,” there is an implication of autobiography, whether on the part of any specific person behind the production I will not speculate. TSIOQUE switches from standard fantasy tropes to a bleak portrait of an artist neglecting his kid and parasitizing his wife, a person also crushed in office hell. And if it was all for this video game, I am afraid it was not worth it. But I give TSIOQUE credit for going in a direction I never saw coming. The recontextualization of earlier scenes might make for an interesting second playthrough, allowing us to realize that when Tsioque escapes her prison cell, for example, she is in reality escaping a crib. As for the tentacled beast, well, my niece has insisted she sees monsters everywhere.

While it feels wholly sincere, TSIOQUE overall has nothing I seek in a video game. My issue is that the animation is not a vehicle for the story and gameplay. Rather, the story and gameplay are justifications for the animation. It feels like so much misapplied skill and effort. The effect reminds me of most early Disney films in that the impressive animation and filmmaking seems wasted telling a story it is impossible to care about, though I would not insult TSIOQUE’s narrative by claiming it is as vapid as classic Disney fare.

One of my all-time favorite adventure games—though not for children—is Daedalic Entertainment’s Edna & Harvey: The Breakout, whose animation, the hectic handiwork of a single university student who depicts himself in the story as seeking group therapy to cope with the job, is limited to the point of obscuring the action. The story is predictable and the backgrounds barely passable. However, the writing is witty and the characters are interesting. A video game supposedly focused on narrative lives and dies by its writing. I never for one second cared about Tsioque or her boring fantasy predicament. But, despite the goofy tone, I was physically trembling from empathy for Edna by the close of her story.

Children’s media can also be more compelling. As I mentioned, Anna’s Quest, a dark fairytale adventure game from the same studio as Edna & Harvey, might superficially resemble TSIOQUE. But while its story is not the deepest and also comes to a surprising ending, shockingly tragic for a children’s title, there is no “everything was fake” copout. In Anna’s Quest, the budget seems to have been directed less toward the underwhelming artwork and more toward a greater variety of settings and a more sophisticated narrative about empathy, death, and fate. Even the goblin guards are more memorable.

Both of these titles, I believe, reflect a better allocation of resources. Would great animation benefit them? Of course. But there are more important things.

Yet these other video games are far longer, perhaps too long, and I am not the target audience for TSIOQUE. I am not an animation buff or fantasy fan and have zero nostalgia for Dragon’s Lair or point-and-click adventure games. TSIOQUE does not want what I want. It does not want complex themes or interesting characters. And had I been exposed to TSIOQUE as a little kid, I expect the influence on my imagination would be indelible. As for what I would have made of the ending—actually, as a kid I could not have solved the puzzles.