Published 31 July 2022

This post is a slightly modified version of my article over at Hardcore Gaming 101.

Today WayForward Technologies is most famous for Shantae and other quality releases and reboots. In 2005, however, WayForward had not yet achieved much of a reputation to boost their marketing. This may partially account for the quiet obscurity of the company’s third-ever fully original IP (after Xtreme Sports and Shantae), Sigma Star Saga, published for Game Boy Advance by Namco Hometek in the United States and by Atari Europe in the UK, France, Spain, and Italy.

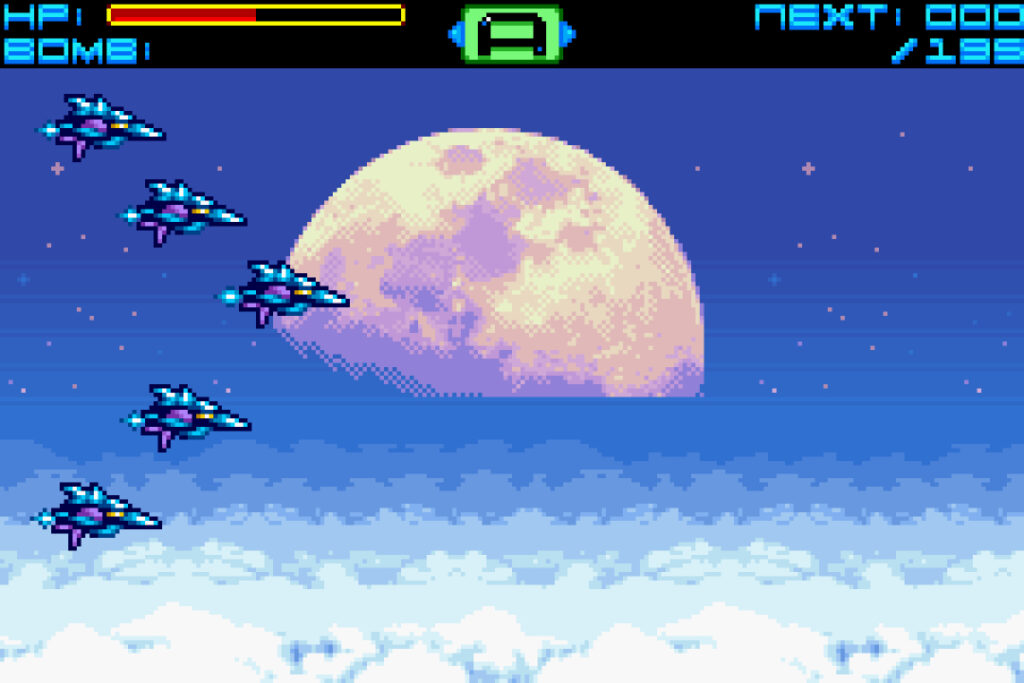

The player assumes the role of Ian Recker, leader of the Allied Earth Federation’s Sigma Team. An opening text crawl describes the extraterrestrial Krill empire wiping out most life on Earth by “[gouging] out a hunk of ocean floor the size of Canada”—extreme material but a generic excuse for blowing up hundreds of enemies. Compare the plots of Axelay or Blazing Lazers. A bog-standard shoot-’em-up stage, side-scrolling like a simplified Gradius, follows. After the boss, however, Saga switches to a top-down perspective, the player controlling Recker to interact with soldiers in a base. For Saga is a shoot-’em-up merged with a Japanese-style action RPG.

Something else accounts for Saga’s minor place in the annals of shoot-’em-up experiments. A frequent issue among gameplay hybrids is that they comprise lackluster versions of each genre incorporated. WayForward’s—more particularly, Philip Cohen and Matt Bozon’s—execution of this ambitious concept is one such jack of all trades but master of none.

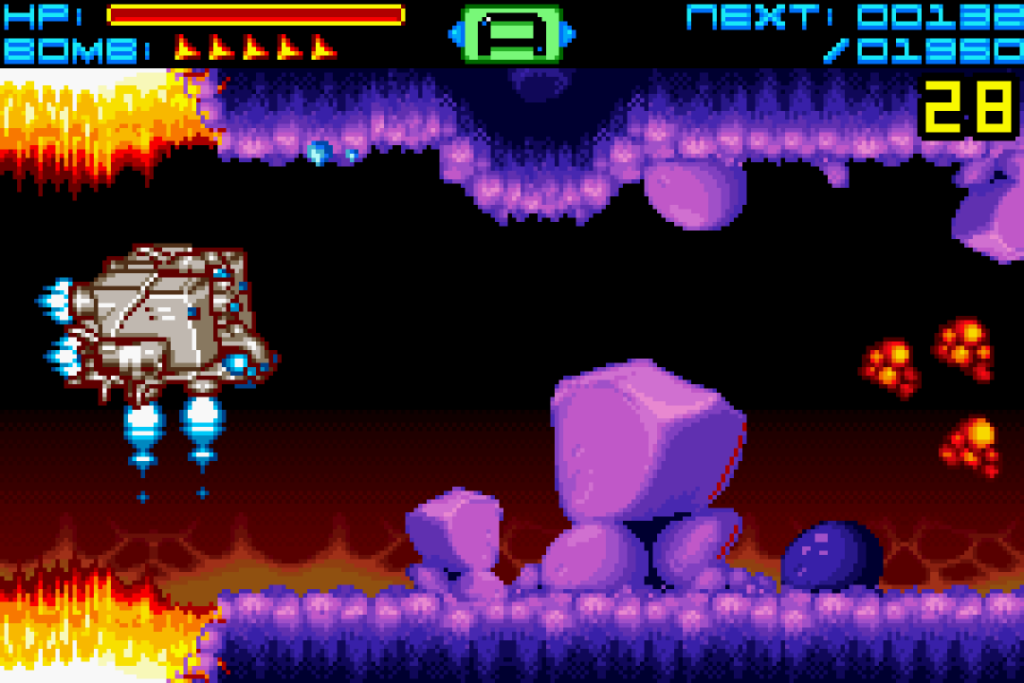

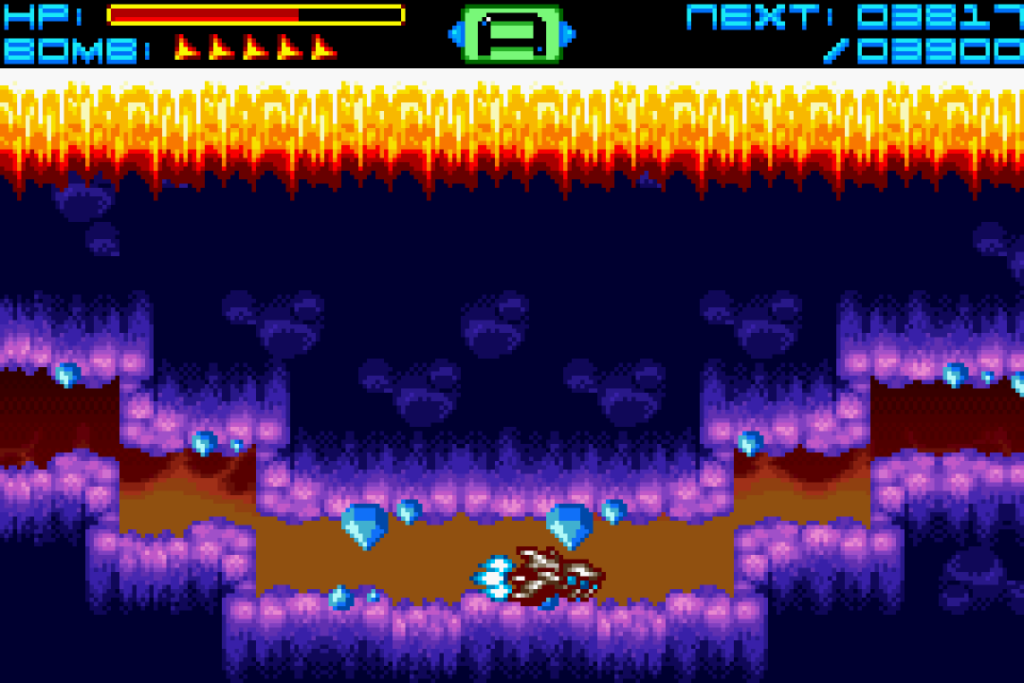

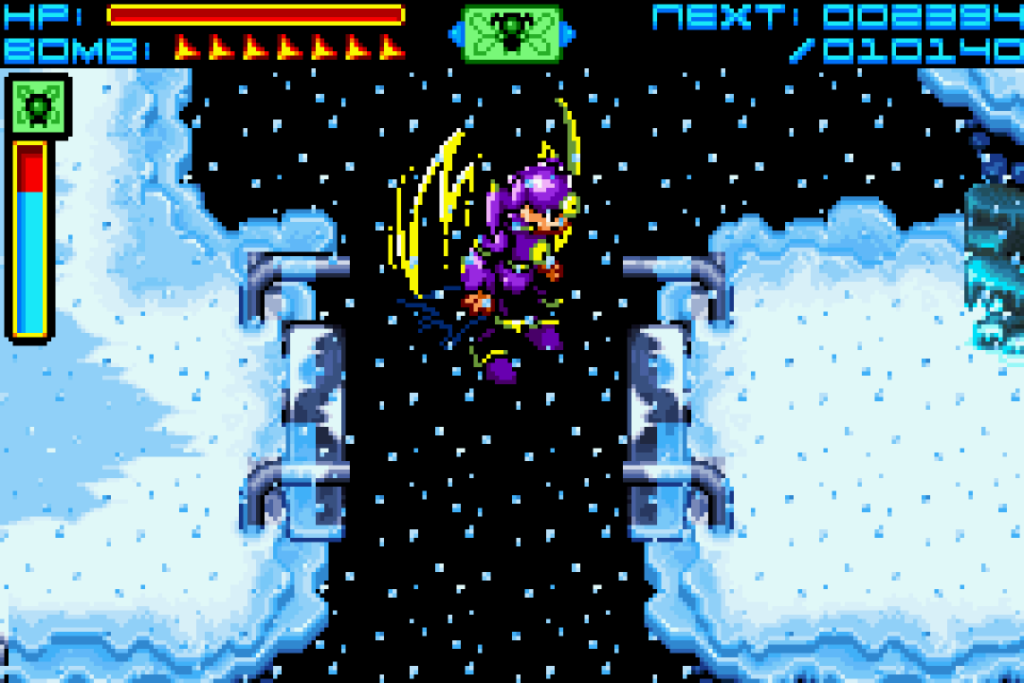

Random encounters in the overworld take the form of shoot-’em-up stages. The story devotes considerable exposition to justifying the random encounters in-universe, a feat few RPGs attempt. A number at the upper right of the screen indicates how many more enemies the player needs to shoot down to clear the stage. Every defeated enemy (and obstacle) drops EXP in the form of collectible glowing blue orbs. Each planet seems to feature a set of looping terrains within which the shoot-’em-up segments occur. Some random encounters are more unique midbosses instead. On the Sand Planet, for example, one midboss can only be damaged when the gaps in its two orbiting shields align. A conventional, scripted shoot-’em-up level concluding with a boss wraps up each chapter.

As in most shoot-’em-ups, crashing into an enemy or the environment results in the instant destruction of the player’s ship. Each ship lost drains a portion of the lifebar, a new, identical vessel blasting from the left side of the screen to continue the action without any loss of momentum or progress. At the same moment, every enemy on screen explodes, leaving no EXP and not counting toward the completion of the stage. Bullets do not explode the player’s ship, instead only scraping off health. An empty lifebar means a game over, condemning the player to lose all progress since the last save point.

Also damaging to the lifebar are the non-shoot-’em-up enemies. Similar to Culture Brain’s The Magic of Scheherazade, in addition to random encounters, enemies scurry about the overworld for Recker to fight with his pistol and, later, Krill Puck. Foes include spinning one-eyed cephalopods, “B-movie zombies,” and bipedal, amphibian-like brutes, one of which (named Hen’nk) is also the first enemy encounter after the prologue. Rewarding no EXP and easily avoidable, overworld enemies offer few incentives to fight them beyond the odd smart bomb or health pack they drop. However, Recker must wipe out three whole space stations of people (!) in overworld rather than shoot-’em-up mode. That every enemy on-screen explodes the instant Recker returns from a shoot-’em-stage lends the action a slapstick quality.

Unlike the explosive arsenal expansion of Gradius, Saga offers only one power-up, the smart bomb. These appear in the overworld as red boxes the player finds inside some statues and enemies. Recker can carry seven at once. During a shoot-’em-up level, a smart bomb will clear the screen of enemies, though effecting this destruction takes a couple seconds.

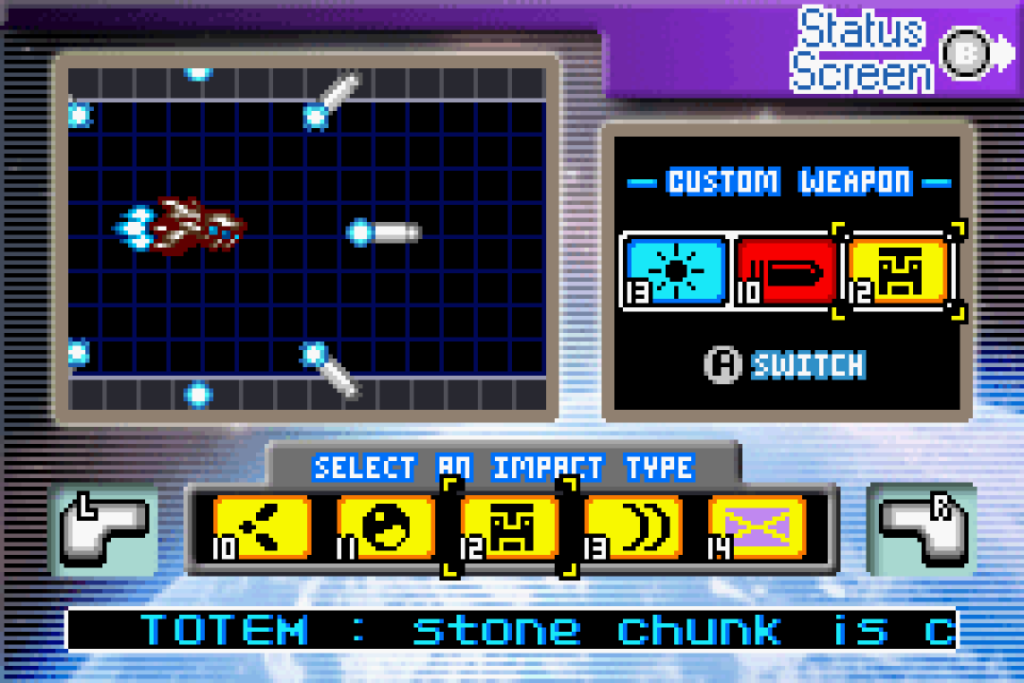

The RPG elements are similarly barebones but include a degree of weapon customization. Each ship has a primary and secondary weapon, the primary customizable and the secondary determined by the vehicle model. To modify the primary weapon, the player equips different Gun Data, collectible one-eyed red disks ensconced throughout the overworld. There are three varieties, one affecting projectile spread, one projectile type, and one projectile impact. Between the dozens of Gun Data are hundreds of possible combinations. The number of combinations viable for combat is no doubt fewer.

Various obstacles fill the overworld that demand certain tools to overcome. To cross minefields, for example, demands clearing a path with a kick of the Krill Puck. This adds a degree of backtracking and optional exploration, but there are no side quests or secrets beyond Gun Data. Though more focused, the result feels unrewarding. Worse are the random encounters, whose swarms of unremarkable bullet sponges initially offer challenge but degenerate into mere busywork with an overdramatic opening fanfare.

The beetle-like Girl Wings allow Recker to fly in short bursts, for the duration of which movement no random encounters can occur. An item Recker attains on the Forgotten Planet allows him to transform into a slime to creep under fences and also deactivates random encounters but at the cost of sluggish movement.

In the oddest design choice, Saga randomly assigns the player one of five possible vehicles, six on the final planet. Their substantial size, speed, and artillery variation adds an element of luck. If Recker ends up piloting the wrong ship for a given challenge, any one encounter might spell loss even for an over-leveled player. For example, on the Forest Planet, a midboss resembling a flying titan arum attacks by spawning tall thorns from the ground and cave ceiling. Early on, a player will likely not be able to maneuver a larger ship around the spikes or shoot down the flower before it sucks the lifebar dry.

The other RPG feature on display is four different endings. WayForward divides the story into six chapters of varying length. Each chapter roughly corresponds to one of the six planets Recker visits, uncreatively named Forest Planet, Fire Planet, and so on, and the Krill starbase orbiting each. The player follows a linear scripted plotline, the only possible divergences in Chapter Six. The narrative is in some ways stricter than in many JRPGs, with minimal optional side content and zero dialogue choices.

Mirroring the gameplay subversion of shoot-’em-up formula, the storyline subversion sees Recker infiltrating the Krill as a spy so that the player fights on the aliens’ side, though only rarely against humans. Learning the Krill’s perspective, the player discovers that both belligerents are equally genocidal, ruthless, and deceitful. Recker’s commanding officer, Tierney (apparently named after Adam Tierney, who worked on Saga), and the Krill’s Tyrannical Overlord massacre their own people in pursuit of the mysterious “alien matter” for the same purpose: not winning the war but instead pure power. The morally complex character Blune states the point explicitly: “We can’t follow Earth or Krill blindly anymore. Good people are being slaughtered on both sides to protect this weapon.” In the final two chapters, the narrative shifts from military intrigue into a borderline cosmic horror story with vengeful ghosts and a “Flesh Deity.”

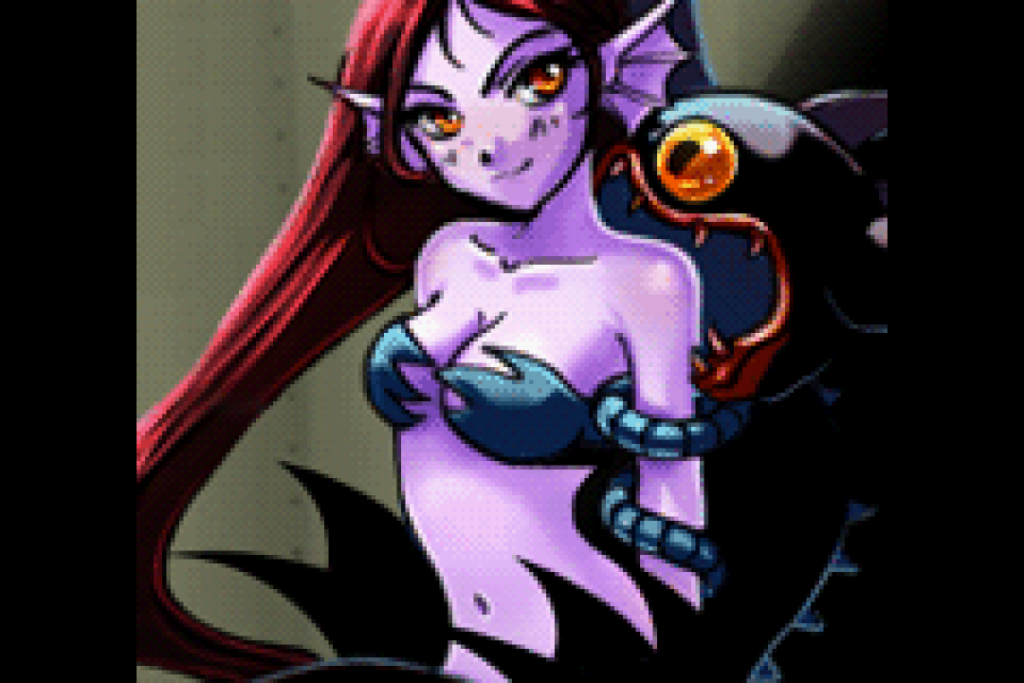

Two factions challenge Recker’s loyalties. So too do the two other stars in the love triangle: the sexy, troublemaking Krill soldier Psyme and the human scientist Scarlet Keys. The four endings correspond to both, neither, or either one of the women surviving. However, the player’s apparent option to choose a preferred girlfriend also proves subordinate to a script that has predetermined with whom Recker’s heart lies. Much of the remainder of the story dips into some sexist tropes—every female character except Scarlet exclusively wears a bikini, for example, feeling more crass than in the silly Shantae series—and the romance does as well. Psyme and Scarlet’s shared screen time is dedicated largely to bickering over the man they immediately fall in love with, though there is also a racism subtext. A lack of chemistry causes the love triangle to feel underwhelming anyway. (Scarlet is also such a sociopath that she uses a grenade to splatter a room full of people and immediately afterward kisses Recker! Yikes!)

None of the endings fully grapple with the scale of death and destruction that fill the narrative. The story also falls short of radicalism sufficient to pay off largely anti-state or anarchist themes. In the best ending, in which both Psyme and Scarlet survive, Recker states the moral in the simplest terms: “Power is a dangerous and corrupting force.” With a mere vague promise that in the future “real leaders” might rebuild the Krill homeworld and with no allusion the possibility of either the Allied Earth Federation or Krill dictatorships democratizing, the conclusion feels almost insulting to an audience presumed mature enough to understand a dark story up to this point.

Saga is a morally ambiguous, tonally serious, and original space opera from creators since famous for comedic releases like Cat Girl Without Salad. Despite the sexual slavery, genocidal war, and a player character who gets an innocent and kind janitor put to death to save his own skin, Saga bears WayForward’s fingerprints. Wackiness bleeds through in details such as the “Girl Wings”—“Wings like a GIRL!!”—and silly side dialogue. In typical Bozon fashion, Psyme and Scarlet are both prickly bodacious babes, and the spinning octopus enemies red as the Squid Baron, as well as the one-eyed Krill parasites, would be at home in Shantae.

Visually, as Shantae does for Game Boy Color, Saga excels for GBA. The character sprites may be oversized, the overworld camera always feeling too zoomed in, but their detail and animations are a treat. At a few key moments, the screen scrolls across static artwork with strong early-2000s Flash vibes. There may be no other GBA game that features a pan over a scantily-clad woman’s body. Saga impresses aurally as well, its music, apparently by Shin’en Multimedia, standing toe-to-toe with other acts of GBA wizardry like Wario Land 4 in sound quality if not in the unremarkable composition.

Sigma Star Saga’s limited save points detract from the pick-up-and-play short sessions suited to a handheld. However, for a GBA title, the gameplay’s simplicity may be appropriate and the story sophisticated. Though less inventive, no doubt the narrative contains more drama and nuance than Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga, for example, or any GBA-original title of my childhood. Saga holds lasting interest as a stepping stone between WayForward’s beginnings and comprehensively excellent later work like Shantae and the Pirate’s Curse and River City Girls. Though falling short of the tight, fast-paced action of The Guardian Legend or the narrative sophistication of a finer RPG, for ambition and sprite art alone Saga warrants its spot in the history of shoot-’em-up genre hybrids.