Koudai identifies Dela Grante as “eidos,” a term used in Platonic philosophy. Plato proposed that there is a world consisting of eide, called “forms” in English. The perceptions of normal human life are nothing but a shadow of these eternal, perfect forms (this is the intended meaning of the famous allegory of the cave). Only a philosopher like Plato can discern these true forms, much as Koudai sees through normal being to find the secrets of the universe. The concepts explored in the Sakaimachi portions of the story, then, are exaggerated and laid bare in Dela Grante. What earlier is subtext becomes text. What earlier is watered down is now perfect. Whereas in the ADMS segment Takuya objects to simulated incest with Ayumi, in the Epilogue he accedes to his biological daughter’s sexual advances with only nominal resistance. Similarly, the brutal theocratic dictatorship of Dela Grante mirrors the abusive power structures of Geo Technics. Soldiers enslave Takuya in a concentration camp to dig through sand and bedrock at the foot of the same sort of lightning-generating “Gazel Tower” that kills Geo Technics’ employees at the sandy Sword Cape construction site.

In Sakaimachi, Toyotomi abuses and drives his workers to death beneath a Gazel Tower under Chief Arima Ayumi’s authority. In Dela Grante, the Chief (or “Porky”) tortures and sometimes kills enslaved dissidents and infidels beneath a Gazel Tower under the authority of God Emperor Arima Ayumi. While Takuya always sides with the corrupt Geo Technics because of his obsession with Ayumi, he vows to kill the God Emperor, stopping short only when he realizes she, too, is his mother.

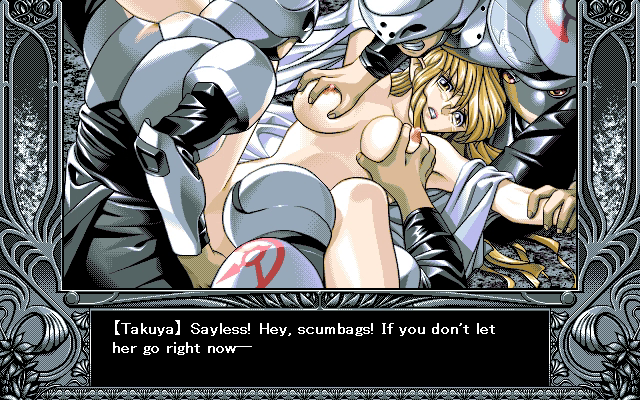

God Emperor Ayumi states that she “will assume all responsibility” for her crimes against humanity and that she “must face appropriate atonement.” But as with the death and pain her incompetence causes the people of Sakaimachi, Ayumi shows little by way of contrition, not using her political power to effect even nominal changes. Sayless’s suicide as four members of the Imperial Guard sexually assault her and call her a “sinner” and her loving relationship with Takuya “the very epitome of depravity” is, to Ayumi, who sent them, merely “a very unfortunate incident.”

Ayumi is so incapable of controlling her troops she cannot order them to spare Takuya, forcing him to flee instead. But in the fantasy scenario Kanno constructs, the brutality of the theocracy and the deaths of many hundreds of priestesses, as Takuya and Yu-no see in the haunting sprawl of the priestess cemetery, is necessary. The rebels are literally wrong to fight: the choice is human sacrifice or the end of the universe. Despite the pain she has and continues to put him through, Takuya readily accepts God Emperor Ayumi’s argument that slavery, torture, and propaganda are the only way to control the rabble, who are simply too pure-hearted to be shown basic respect. Even Amanda, the rebel leader, seems to get over her torture and the murder of her comrades. For in the story, the God Emperor’s antihuman perspectives are, like Koudai’s, correct.

To accept the traditions of the theocratic dictatorship is to accept fate as well, to accept the path Koudai set out for Takuya. For Takuya learns from Ayumi that even the rite of the priestess is “a predetermined fate” that he cannot stop. Rather than resist the dictatorship, Takuya becomes a collaborator. Accepting abusive authority, accepting that there is no freedom in either causality or in society, accepting fate—accepting, in summation, Koudai’s outlook and control, is maturity. When Takuya weeps over Mitsuki’s body and says like hell will he allow fate to control their lives, he is not heroic but naïve.