The writing style is also somewhat changed. Baum’s prose in The Wonderful Wizard is simple, as befits a children’s fairy tale, but in The Marvelous Land the material is somewhat more grownup and slathers on more jokes and witty repartee:

“My friend is right,” said Nick Chopper, who had been polishing his breast with a bit of chamois-leather. “Jinjur is still the Queen, and we are her prisoners.”

“But I hope she cannot get at us,” exclaimed the Pumpkinhead, with a shiver of fear. “She threatened to make tarts of me, you know.”

“Don’t worry,” said the Tin Woodman. “It cannot matter greatly. If you stay shut up here you will spoil in time, anyway. A good tart is far more admirable than a decayed intellect.” [Note the double entendre: “tart” is a rude word for a promiscuous woman.]

“Very true,” agreed the Scarecrow.

“Oh, dear!” moaned Jack; “what an unhappy lot is mine! Why, dear father, did you not make me out of tin—or even out of straw—so that I would keep indefinitely.”

“Shucks!” returned Tip, indignantly. “You ought to be glad that I made you at all.” Then he added, reflectively, “everything has to come to an end, some time.”

“But I beg to remind you,” broke in the Woggle-Bug, who had a distressed look in his bulging, round eyes, “that this terrible Queen Jinjur suggested making a goulash of me—Me! the only Highly Magnified and Thoroughly Educated Woggle-Bug in the wide, wide world!”

“I think it was a brilliant idea,” remarked the Scarecrow, approvingly.

“Don’t you imagine he would make a better soup?” asked the Tin Woodman, turning toward his friend.

“Well, perhaps,” acknowledged the Scarecrow. (182–183)

The characters are mean in this scene. 😅

Baum narrates the action in a more detailed and complex way than the simple, folktale-like adventures of the previous novel. Compare the whole chapter devoted to the battle against only the jackdaws in The Marvelous Land to the less than one chapter devoted to the battles against the Wicked Witch of the West’s wolves, crows, bees, Winkie slave soldiers, and Winged Monkeys in the previous novel.

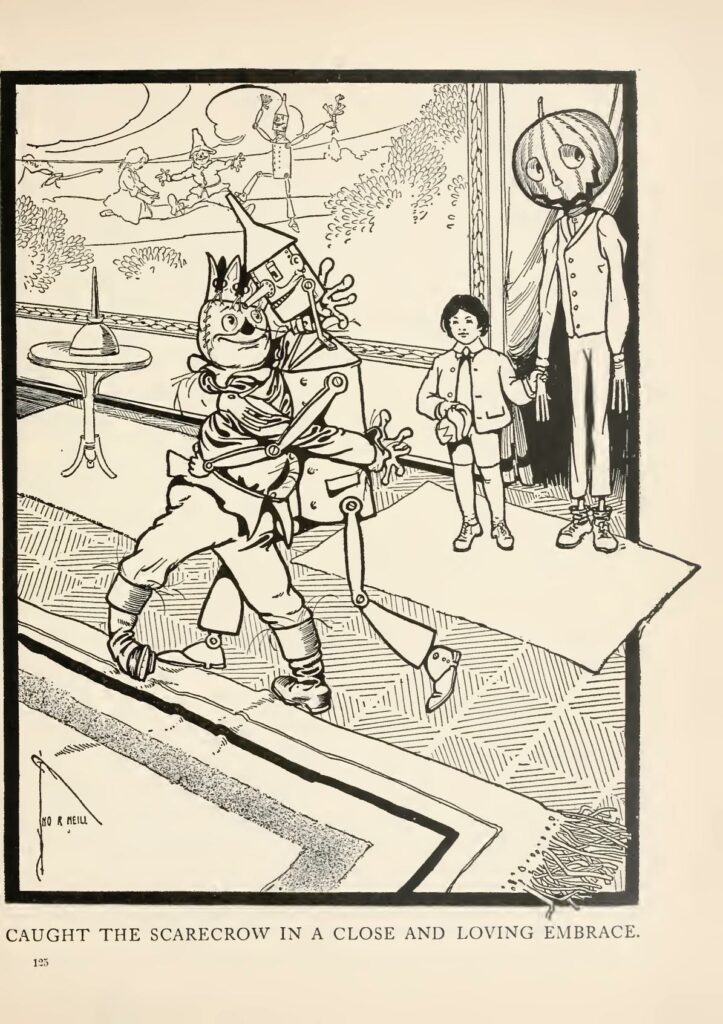

In an afterword, Peter Glassman suggests this is heightened theatricality, reflecting that Baum wrote The Marvelous Land specifically to adapt it for the stage. This would explain why Baum devotes so many words to describing the Army of Revolt’s colorful uniforms. Baum may have imagined them being performed by Broadway chorus girls. This also explains the prominence and vaudevillian antics of the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman. These characters were popular for their humorous portrayals in the 1902 musical The Wizard of Oz, a precursor to the 1939 film, to the extent that that Baum dedicated The Marvelous Land to Fred A. Stone and David C. Montgomery, the comedians who played them. (Comedians, by the way, known for their blackface minstrel performances! Yikes!) Baum was just writing what he meant to be their next role. Though the novel proved a success, the stage adaptation underperformed, perhaps because he for some reason entitled it The Woggle-Bug, which is about the same as Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace being entitled Jar Jar Binks.

The general rule is that Baum’s writing in The Marvelous Land goes into much more detail than in The Wonderful Wizard. The greater elaboration is, for instance, why the many occasions the Scarecrow is skinned and gutted in various forms seem more disturbing here than in similar scenes of that more famous predecessor. There is a decent amount of violence, as well, with no fewer that two instances of eyes being threatened with sharp, piercing points, and Tip being stabbed by one of Jinjur’s soldiers.

The Oz novels are early examples of fantasy worldbuilding as readers today would understand it. Whereas Tolkien approached this matter with weight and care, for Baum the effort is more slapdash, yielding, perhaps, more bizarre and idiosyncratic creations. In The Marvelous Land, Dorothy’s adventures are treated as a legendary and momentous chain of events with profound political ramifications. They would be, were they to have happened in a real series of countries, but it is strange (and awesome) for Baum to recontextualize fairy tale adventures as shaking up politics and destabilizing society. This also results in Tip’s exposition to Jack hilariously implying Kansas is an exotic land. The Scarecrow is now the king of the Emerald City, the crown sewn to his head, though its weight causes his face to sag. The Tin Woodman, meanwhile, has become the uncontested dictator and self-proclaimed Emperor of the Winkies. Being the character with the most compassion, he is, I would hope, nicer to them than the Wicked Witch, yet it is disquieting to see the Tin Woodman no longer a tragic lumberjack but leading a lifestyle of extreme luxury as a self-identified “Absolute Monarch” (285).

The story is more morally ambiguous than in the previous novel. There are still clear good guys and bad guys, but the villains Mombi and especially General Jinjur are no longer literal beasts or slave-driving Wicked Witches, and the protagonists, as I have suggested, are of rather dubious goodness. The Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman are both dictators and bumbling doofuses. While friendly, the Scarecrow is acknowledged to have unjustly stolen the throne (which the Wizard also unjustly stole with Mombi’s assistance). He also apparently presides over some alarming laws, such as one that sentences those who damage a certain palm tree to death seven times (194). Still naïve to a point of tragedy, neither the Scarecrow nor Tin Woodman have realized that the Wizard was a fraudster or that they were already wise and kind without his ersatz magic. The powerful Glinda the Good—whose name is literally “the Good”—is imperiously carried around by twelve servants in a palanquin (248), has an international spy network (242), threatens death on her enemies (alarming the Tin Woodman), and is confirmed to have inherited some of the Wicked Witch’s slaves: “the Winged Monkeys are now the slaves of Glinda the Good,” as the Scarecrow tells Tip and Jack (117).