Published 11 November 2022

This continues from my previous post about The Marvelous Land of Oz. Please consider reading that one first.

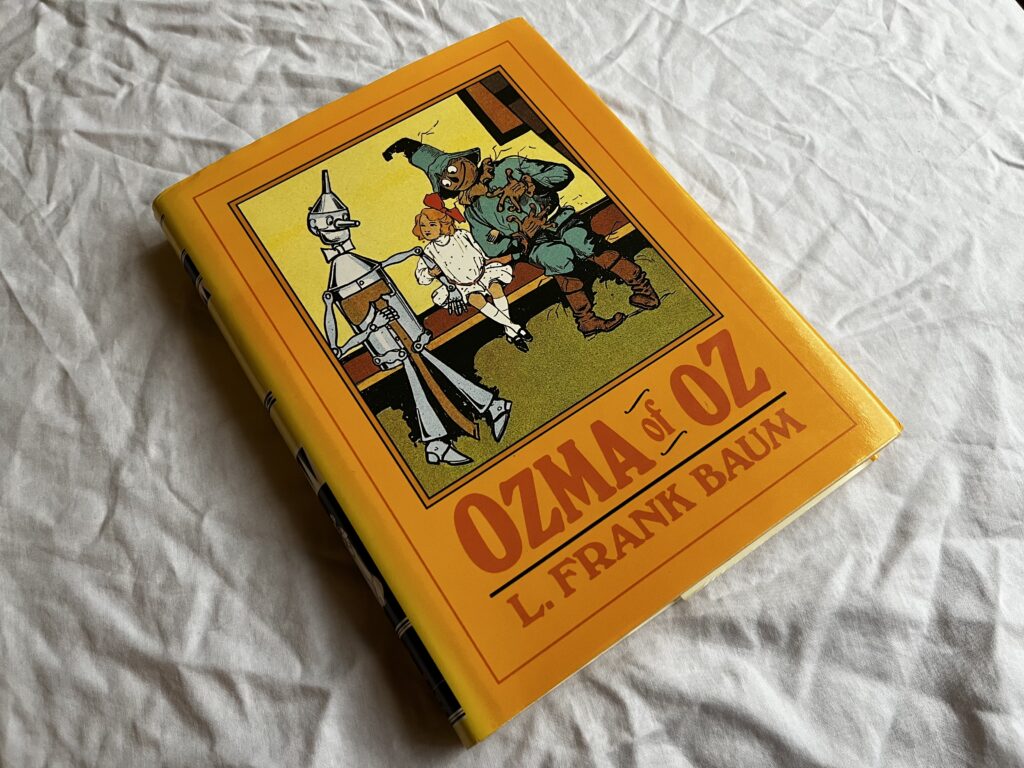

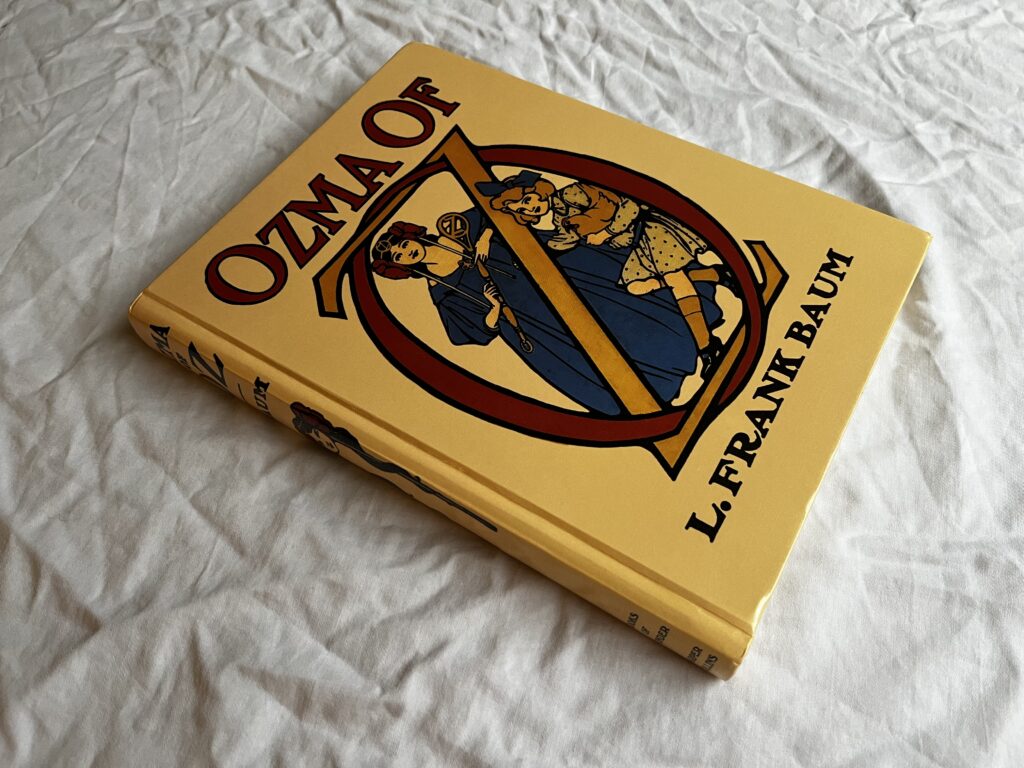

Ozma of Oz, the third Oz novel, published in 1907, shows that L. Frank Baum had no talent for titles. The previous title, The Marvelous Land of Oz, is generic to the point of being meaningless. Since it is about the rise of Ozma of Oz, if anything, it should be the book bearing that name.

The title Ozma of Oz is also comically misleading: only the final two chapters of the twenty-one present in Ozma of Oz feature the Land of Oz, and our favorite transgender princess, Ozma of Oz, is not the protagonist. However, Ozma of Oz is abbreviated. Given its length, the somewhat more accurate full title seems more sixteenth century than 1907. It is Ozma of Oz: A Record of Her Adventures with Dorothy Gale of Kansas, Billina the Yellow Hen, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, the Cowardly Lion and the Hungry Tiger; Besides Other Good People Too Numerous to Mention Faithfully Recorded Herein by L. Frank Baum the Author of The Wizard of Oz, The Land of Oz, etc.

Ozma of Oz is also much better than the previous two books.

According to the Author’s Note, Baum’s readers wanted more Dorothy. So she would be the protagonist of every Oz novel until the seventh, The Patchwork Girl of Oz. It may be relevant to mention that Baum likely intended to end the series with the sixth book.

Dorothy Gale is aboard a passenger ship sailing for Australia with Uncle Henry when a terrible storm blows her into the sea, where she clings to life in a floating wooden chicken coop that also blew overboard. Compared to the house being carried away in the first novel, this is more distressing because it seems more realistic—houses do not spin around intact inside a tornado, but a storm could blow a child into the ocean. Dorothy and the one surviving hen, Bill, wash up on the shore of a strange foreign land. Dorothy quickly realizes this is a “fairy country” or “fairyland” like Oz because Bill can talk there. (Note that in the novels, Oz and the other fairy countries are real and not dreams.) Being an unimaginative stick-in-the-mud, Dorothy says Bill must be named Billina because “Bill” is a boy’s name, Billina says she doesn’t care, and then they set out into the wilderness.

Dorothy learns from a robot named Tiktok that she is in a country called Ev on the other side of the Deadly Desert that surrounds and isolates Oz. (Tiktok was constructed by Smith & Tinker, not ByteDance.) The King of Ev was a cruel man named Evoldo. Tiktok, not being alive, was the only of Evoldo’s servants he did not beat to death. After his reign of terror apparently depopulated much of the land (he killed a lot of people, and almost nobody seems to live in Ev), Evoldo sold his wife and children as slaves to the Nome King. Later, remorseful, Evoldo killed himself. This is a lot darker than the previous books! Ozma of Oz, along with fan favorites the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion, as well as the new Hungry Tiger and Oz’s twenty-seven-man army, arrive in Ev in time to rescue Dorothy and Billina from the local dictator, Langwidere. From here, Dorothy joins Ozma on a journey to free the Royal Family of Ev from the diabolical Nome King, Roquat of the Rocks.

(Wikipedia claims that the Nome King is named Roquat the Red, but he only takes on that name later, presumably because he becomes so consumed with rage that he turns red.)