Published 23 November 2022

This is the third post in my series about the Oz books that come after the well-known one in which Dorothy follows the Yellow Brick Road. Please read those first, or else some of this one will seem even more like nonsense.

For reference, please remember that these are the first six Oz books L. Frank Baum wrote:

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

The Marvelous Land of Oz

Ozma of Oz

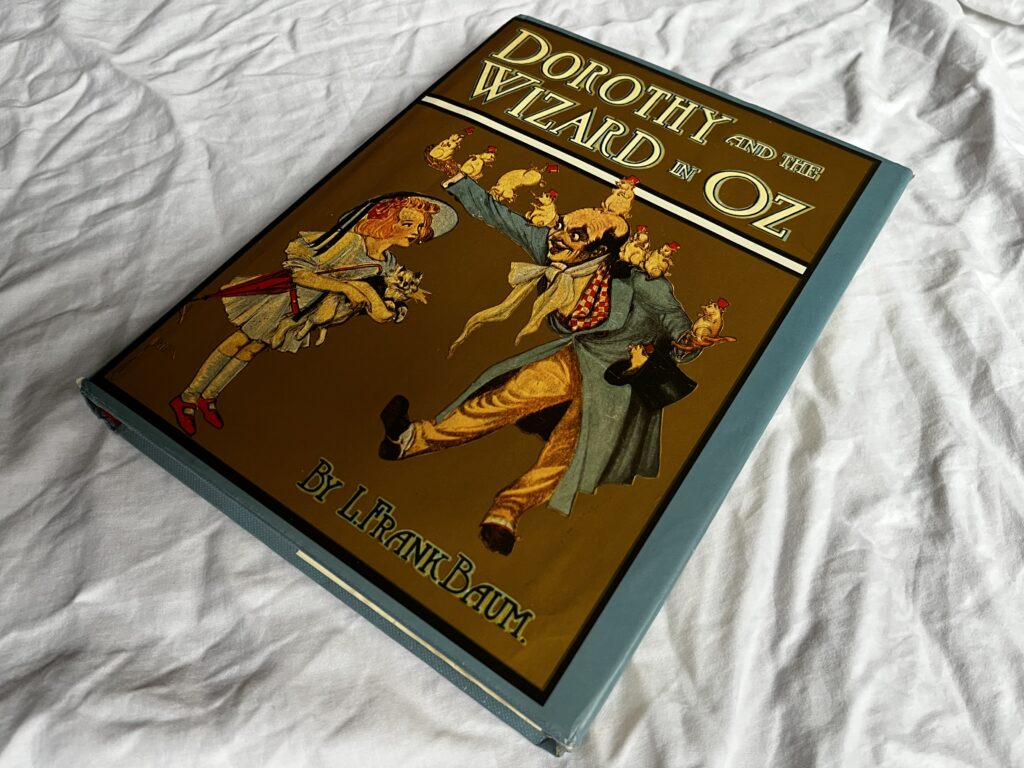

Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz

The Road to Oz

The Emerald City of Oz

Ozma of Oz marks a shift in the Oz series. In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and The Marvelous Land of Oz, the characters’ journeys occur within the Land of Oz. In these stories, Oz is a perilous, exotic place. It is full of environmental dangers, violent political actors, and, in the first book, even deadly monsters that the characters must overcome. After the ascension of Ozma in the end of the second book, the chaos of the primordial Oz is “tamed,” as though Ozma is a mythic culture hero, and the land becomes a magical utopia. Instead of facing danger in Oz, the characters face adversity abroad before finally returning to Oz.

(There are still, probably unintentional, hints that Oz may not be so pleasant as it appears. Ozma, for example, is greatly amused when someone is injured and begins crying. I suppose that matches her mean streak in The Marvelous Land of Oz.)

The fourth book, Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, given at the top of every other page as Little Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, falls into this pattern. Despite the title (Baum is so bad at titles!), Dorothy and the Wizard spend the majority of the book not in Oz but in a series of underground countries beneath California connected by caves. I wonder whether this is an allusion to the underground world of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, no doubt an influence on Baum.