Not only the sad moments seem more convincing but the happy ones too: “the dinner was no sooner finished than in rushed the Scarecrow, to hug Dorothy in his padded arms and tell her how glad he was to see her again” (196). Ozma, for her part, kisses Dorothy in two different scenes. (“I’ve noticed that many queer things happen in fairy countries,” as the Wizard points out on page 67.) Baum also lends a bit of psychological depth, relatively, to their relationship: “Ozma was happy to have Dorothy beside her, for girls of her own age with whom it was proper for the Princess to associate were very few, and often the youthful Ruler of Oz was lonely for lack of companionship” (231).

Note that Baum mocks royal practices when the dragonettes speak to Dorothy of their alleged noble Atlantean descent (169) but here takes for granted that the princess of his utopia cannot hang out with the common people. This is despite the ordinary people being so good there is no crime in Oz: “it must be stated that the people of that Land were generally so well-behaved that there was not a single lawyer amongst them, and it had been years since any Ruler had sat in judgment upon an offender of the law” (237). In any case, there is a stronger sense of camaraderie than in the wacky military discipline and glib attitude toward the friends lost to the Nome King in Ozma of Oz. Or perhaps I am just more favorably inclined toward Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz.

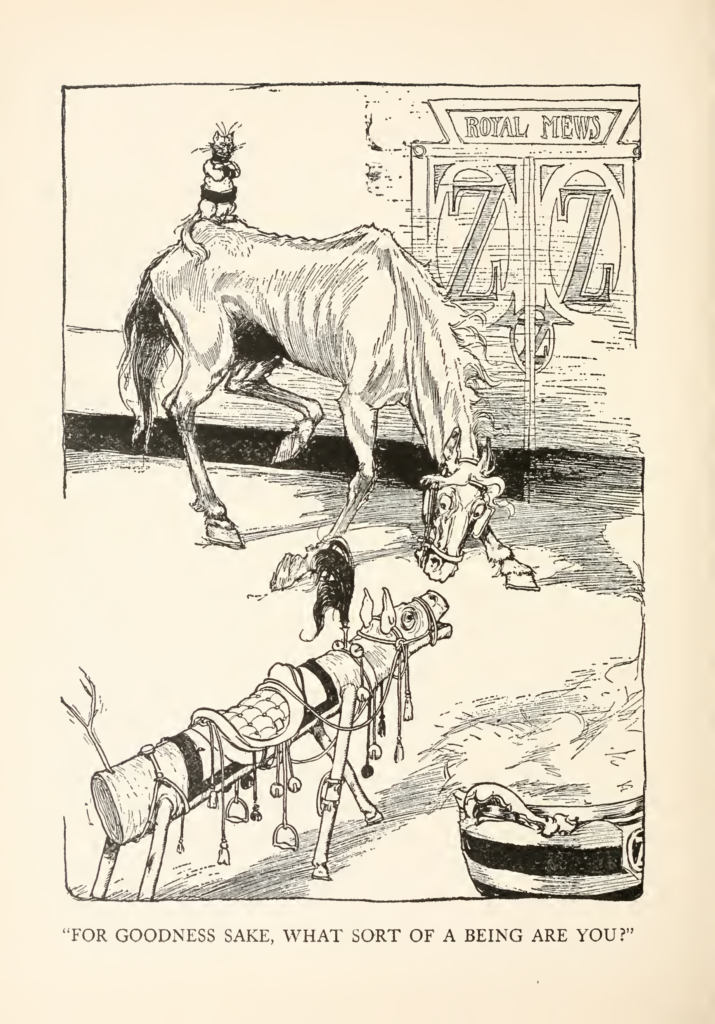

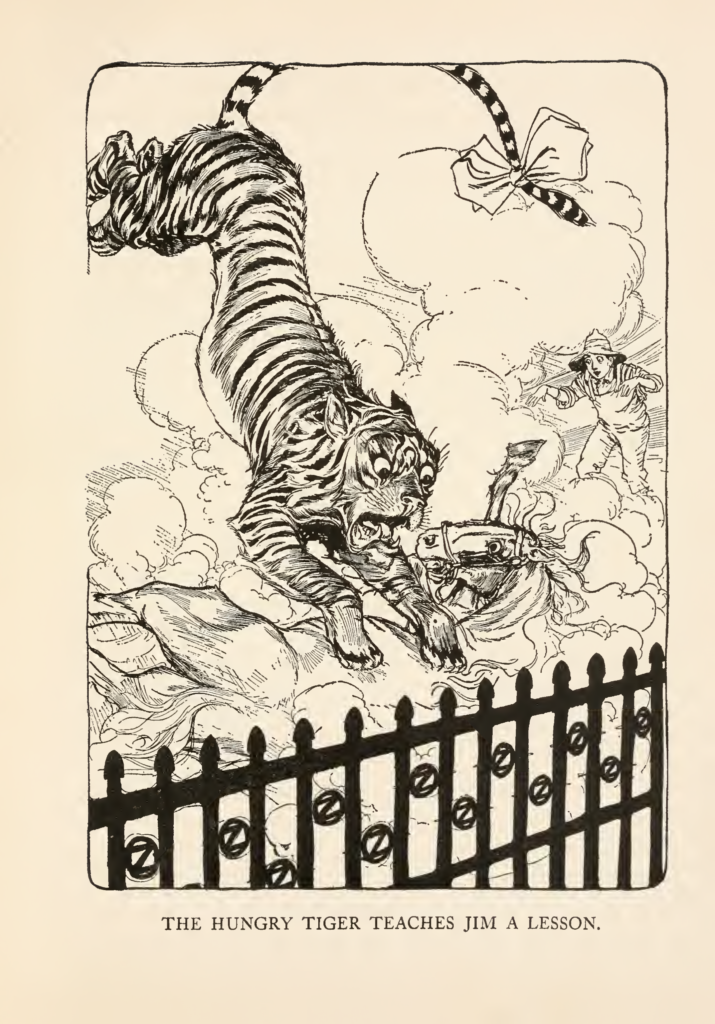

The conflict that arises between these characters feels somewhat more organic as well. When Zeb says, “This is a fine country, and I like all the people that live in it. But the fact is, Jim and I don’t seem to fit into a fairyland” (252), the reader believes it. Jim is treated as royalty but is too confused by the meals he cooks and agitated to the point of violence by the presence of the Cowardly Lion and Hungry Tiger and Sawhorse. (Note that the Sawhorse is now called the Sawhorse, without a dash, whereas before it is always called the Saw-Horse.)

The relatively grounded Zeb, Jim, and Eureka cannot be at home in Oz, where all animals live in peace with humans and each other, and where Eureka being a cat and trying to eat smaller animals gets her imprisoned and almost executed. There is also an amusing dynamic where Zeb is a simple country boy, overwhelmed and bewildered, while Dorothy, from her past adventures, takes the bizarre occurrences as pretty normal. At one point, faced with a story of the champion Overman-Anu’s grizzly death, Dorothy shrugs the impending danger off with, “They can’t be worse than the Wicked Witch or the Nome King” (111). This may be why Baum introduces the otherwise bland and unnecessary Zeb to the story: Dorothy can no longer provide relatable grounding for the action.

Neill’s illustrations undergo another change this time around. Instead of the relatively flat colors in Ozma of Oz, now his full-page, full-color Art Nouveau drawings are realized in bright, luscious watercolor. While no part of the production can be considered lazy or sloppy, the effect does not necessarily always serve the book for the better. In particular, aside from the ugly and blurry cover art, the Wizard’s nose and cheeks are so red he appears to be suffering a flare-up of rosacea.