Published 6 December 2022

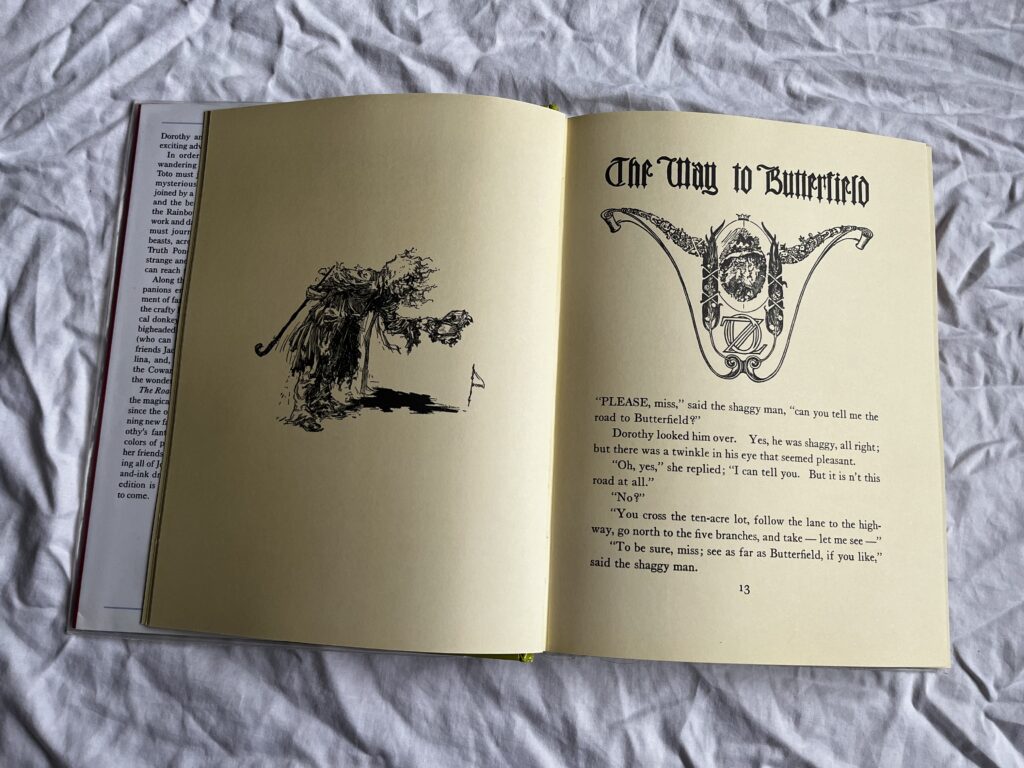

“PLEASE, miss,” said the shaggy man, “can you tell me the road to Butterfield?” (13)

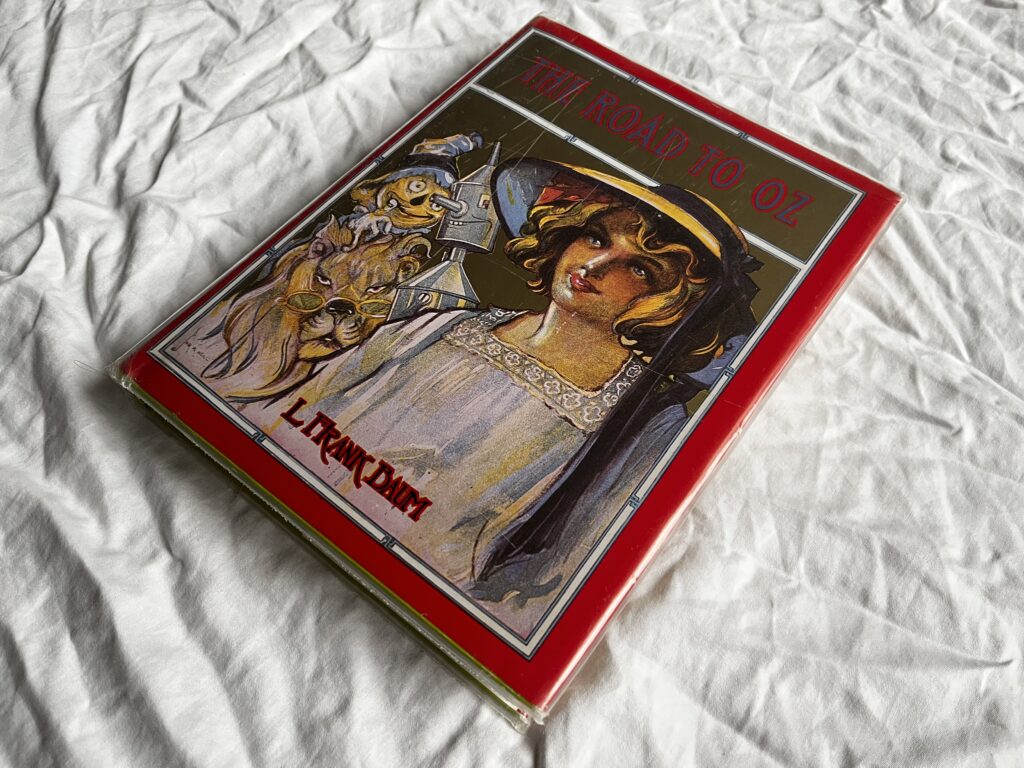

Together with John R. Neill’s almost ghostly illustration, this makes for a striking start to The Road to Oz, the fifth installment of the Oz series. This is the fourth of my posts about the original sequels to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and I recommend reading each of the ones that preceded it. Sorry for giving you homework, but this will make some of my commentary below will make more sense. And they’re interesting posts in their own right.

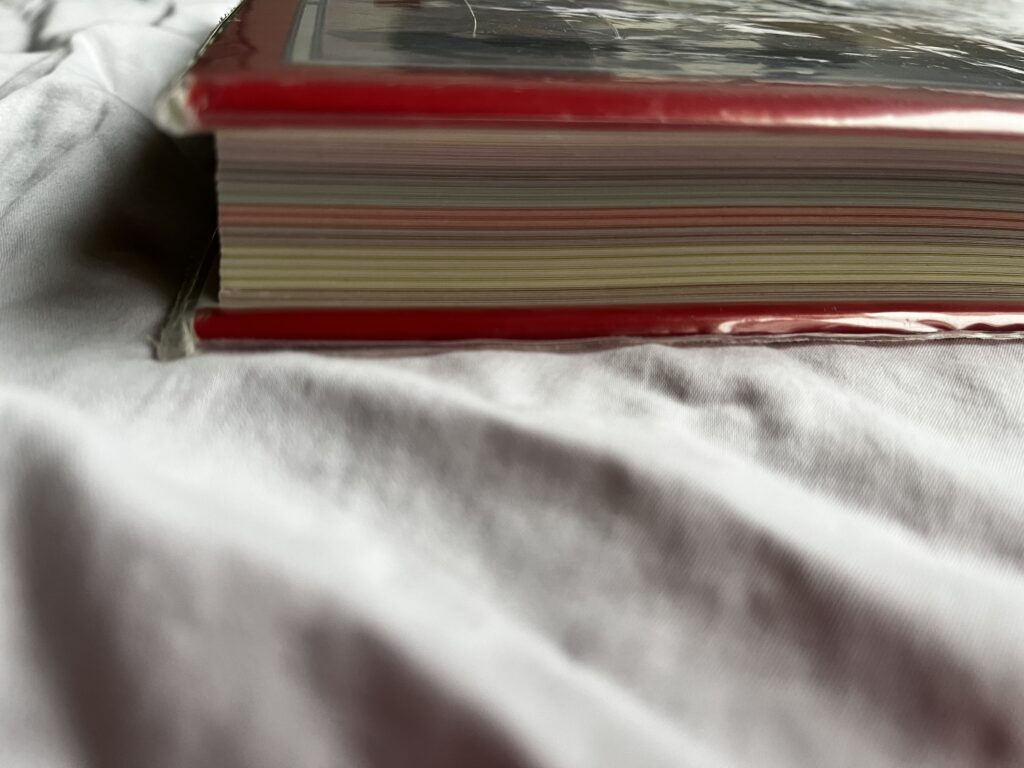

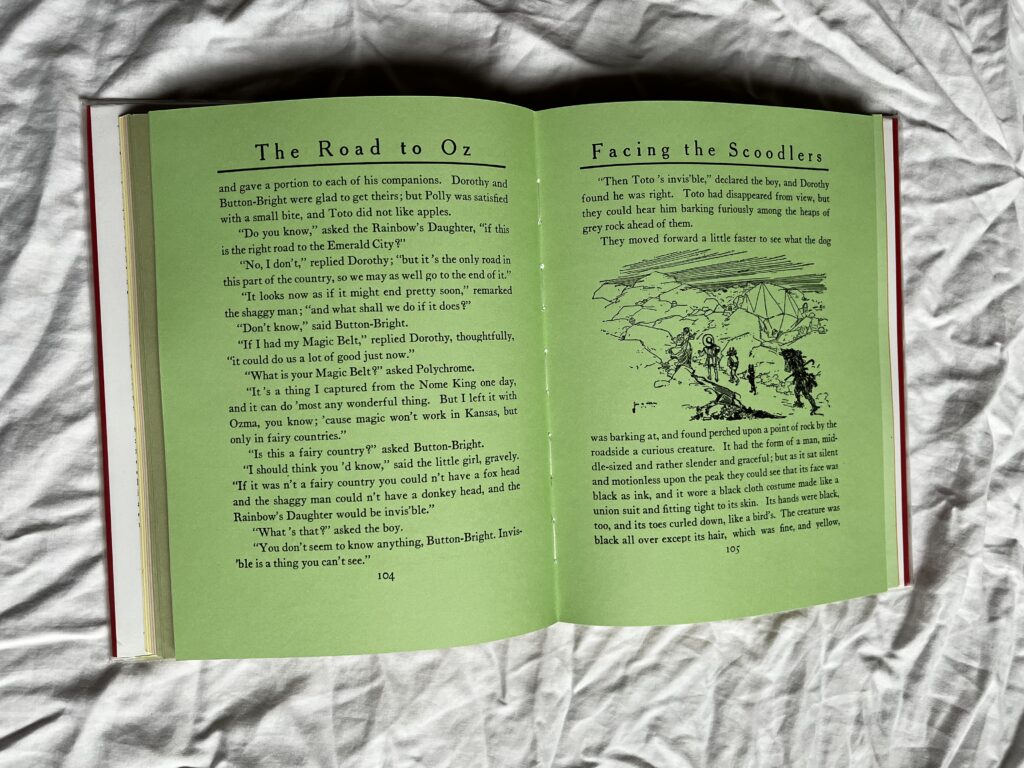

Each Oz book is, physically, an art object. Uniquely, The Road to Oz has no color illustrations. Instead, in the first edition of 1909, the text and pen drawings are printed directly onto colored paper, so that the book has a rainbow pattern, from yellow, to violet to light green to lime green to orange to brownish green to neon green to brown.

There is no clear meaning to the points at which the page color shifts. It makes for a highly unique volume, physically, and alludes to the character of the rainbow girl Polychrome, a sky-fairy like those Dorothy glimpses in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz.

These photos demonstrate the effect of the text and drawings on colored paper. This edition is apparently the first reprinting to reintroduce the original colors. While this accounts for the lack of full-color drawings, Neill lavishes his pen artwork with exquisite detail.