Published 24 February 2023

Introduction

Since October, I have been writing about L. Frank Baum’s original Oz novels, beginning from the less familiar second installment. They have almost no connection to the better-known 1939 musical, which already shaved the edge and personality off Baum’s work. I recommend readers of this post not familiar with the Oz books check out my earlier articles first. The Emerald City, in particular, follows up the plot of Ozma of Oz. If this post might be easier for you to share there, you can also find it on Tumblr.

At last, I reach the sixth book, The Emerald City of Oz, the grand finale (or not). In addition, The Emerald City serves as a thematic capstone and statement of the series’ overall values with some interesting political implications, as I will explore in a second post, “The Politics of Oz.”

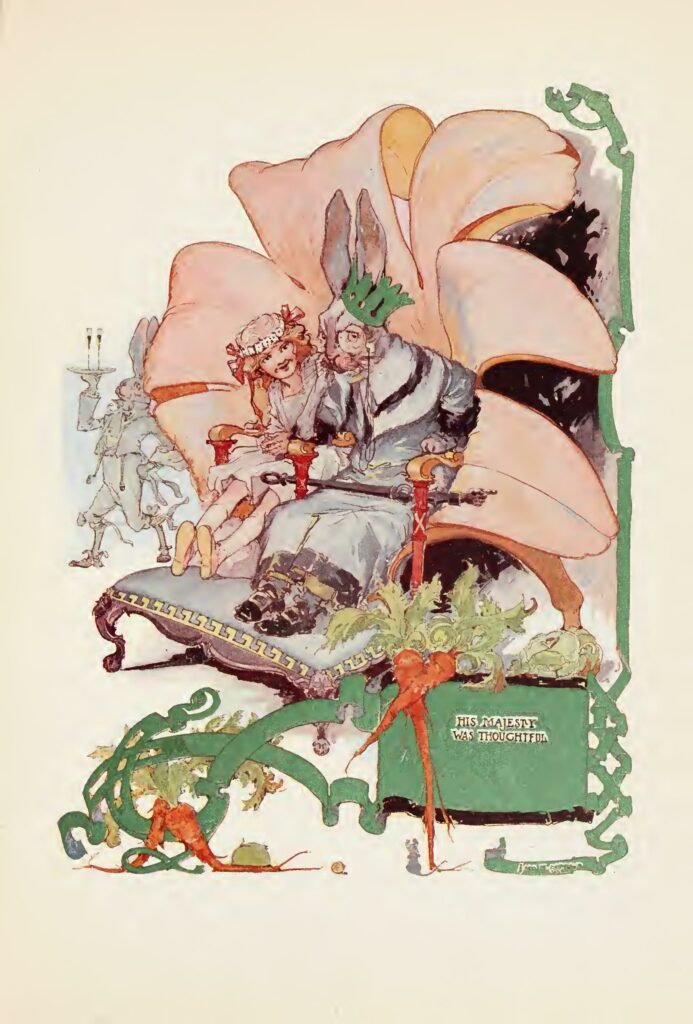

The original 1910 printing of The Emerald City of Oz used sparkly, metallic green ink in John R. Neill’s many lush water color illustrations. Is it supposed to be emerald? Subsequent runs of The Emerald City removed this feature, something like the later printings of The Road to Oz dropped the colored pages, removing what made the book unique. However, as with the previous installment, my Books of Wonder edition restores this feature for the first time in decades, allowing me to view the drawings as Baum and Neill intended. The metallic shininess of the ink, sadly, cannot be preserved in the scans you see here.

(For some reason, I notice that the Archive.org edition of The Emerald City includes at least one color illustration my print edition lacks, the above one depicting Dorothy seated with the King of Bunnybury.)

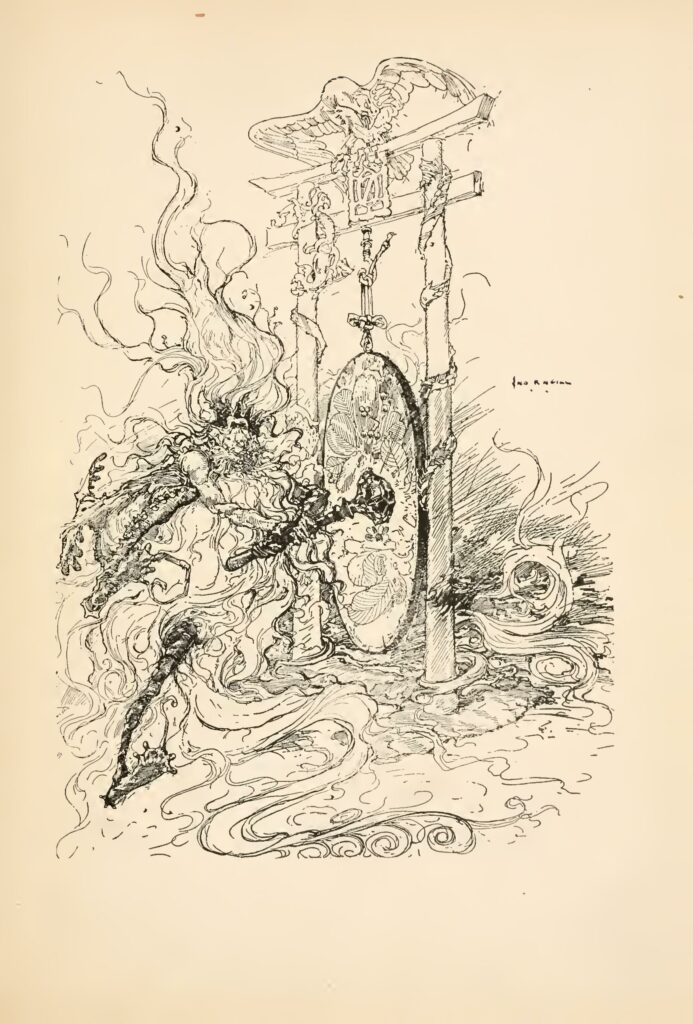

Neill has continued developing the scratchiness and intricate detail of his drawings to an extent that some of them are difficult to interpret at a glance. The colored illustrations in particular often feature baroque detail in such flat and muddled color, most of the things depicted absent from the text because Neill had to fill the space with something, that they demand deciphering more than viewing. But non-color illustrations can end up similarly opaque.

The above scary picture of the Nome King beating a gong to summon his minions took me particularly long to figure out, his face, contorted with rage, all wrinkles.

The Art Nouveau style is confident and distinct, trendy at the time and today full of the foreign strangeness that adheres to the aesthetic tastes of a past generation. Now at the height of his form, Neill completely avoids (sadly) the scary and upsetting style of illustration that fills The Marvelous Land of Oz, and so I have little else to say about them (except that I wish he drew the Wizard as tiny as Denslow depicted the “little man”).

The Emerald City features an escalated conflict and brings back concepts and characters from the past novels. Notably, for the first time since The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Baum mentions the existence of danger in Oz: the Kalidahs, Fighting Trees, and Hammer-Heads. Trying to keep Oz a heavenly utopia, Baum feels the need to address that the Hammer-Heads are “Wild People” but do not harm anyone who stays away from their mountains in the Quadling Country and adds that the Kalidahs, so menacing before, “[are] now nearly all tamed” like the Cowardly Lion and Hungry Tiger (32).

“I suppose every country has some drawbacks, so even this almost perfect fairyland could not be quite perfect” (33), Baum says in the narration, getting defensive against, I can only assume, me specifically. Contrary to what he says, by the way, in later books he shows the Kalidahs are not tamed and that Oz is home to many more people who do not submit to Ozma because keeping a single detail consistent was as unimaginable to Baum as the colour out of space is to human eyes in that Lovecraft story.

Despite this attention to detail, the continuity, as usual, seems careless to a reader today. Baum forgets the basic geography of Oz. In The Emerald City, he depicts a number of towns under the protection of Glinda, the Good Witch of the South, but apparently situates them in the northern Gillikan Country (242). On page 46, he even has Guph say Glinda lives in the northern country, not the south! For a writer whose most famous villain has a name emphasizing her cardinal direction, you’d think Baum would remember which country is on which side. He introduces a region outside of Oz, the Ripple Lands, where the land shifts like an ocean, perhaps to display his total contempt for consistent geography.

The truth is that Baum did not care about continuity whatsoever because his artistic and financial goals had nothing to do with it. This is why every book in the series contradicts earlier material, as I most especially describe in the post about Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz. Now that I am finished going “Well akshually” and pushing my glasses back up my nose, let’s proceed to the story.