The End of Oz?

These two plotlines merge once, after Baum uses the Rigmaroles to make fun of bloviators and the Flutterbudgets to make fun of neurotic people, Dorothy’s caravan reaches the Tin Woodman’s gleaming palace in the Country of the Winkies. There, the reader is finally spared from filler. The Tin Woodman has heard from Ozma. She learned of the Nome King’s impending invasion from the Magic Picture, which lets her see anyone she wants anywhere in the world at any time. Dorothy and her friends are somewhat perturbed to learn they’re all about to die, or worse.

“When our enemies break through this crust they will be in the gardens of the royal palace, in the heart of the Emerald City. I offered to arm my Winkies and march to Ozma’s assistance; but she said no.”

“I wonder why?” asked Dorothy.

“She answered that the inhabitants of Oz, gathered together, were not powerful enough to fight and overcome the evil forces of the Nome King. Therefore she refuses to fight at all.”

“But they will capture and enslave us, and plunder and ruin all our lovely land!” exclaimed the Wizard, greatly disturbed by this statement.

“I fear they will,” said the Tin Woodman, sorrowfully. “And I also fear that those who are not fairies, such as the Wizard, and Dorothy, and her uncle and aunt, as well as Toto and Billina, will be speedily put to death by the conquerors.”

“What can be done?” asked Dorothy, shuddering a little at the prospect of this awful fate.

“Nothing can be done!” gloomily replied the Emperor of the Winkies. “But since Ozma refuses my army I will go myself to the Emerald City. The least I may do is to perish beside my beloved Ruler” (253–254).

After the party visits the Scarecrow at his new apartment, a building shaped like an ear of corn, they return to the Emerald City to die alongside Ozma. Dejection prevails.

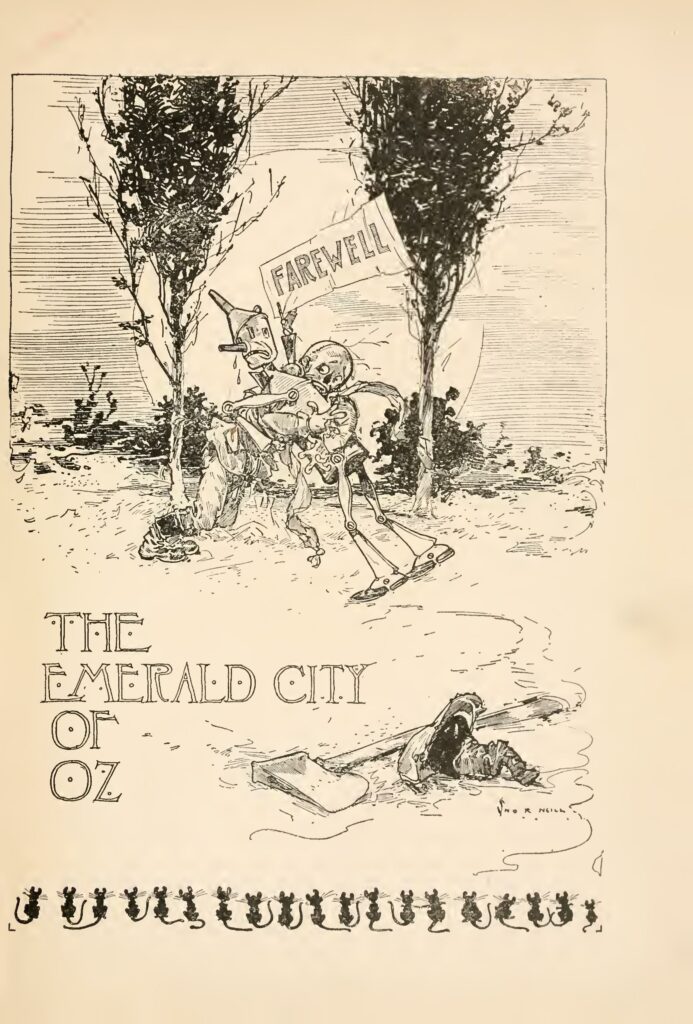

Opening the novel is an ominous illustration of the Tin Woodman and the Scarecrow embracing while weeping sadly. The Tin Woodman holds a flag reading “Farewell,” implying that not only is this the end of the series but that the end will be disastrous. Although I think Baum largely fails to realize these characters’ respective alleged compassion and intellect, seeing them in this condition still legitimately moved me a little.

The Scarecrow counsels everyone to remain happy until the very end, for there is no reason to spoil the brief time they have left before the “country is despoiled and our people made slaves” (259). Since her behavior has become increasingly inhuman and difficult for a reader to sympathize with, Ozma herself does not worry about the Nome King the tiniest bit (263), somewhat undercutting the drama. Even after the others express their alarm, only after dinner does Ozma begin discussing whether she should do something about the impending invasion. Rejecting Omby Amby and the Scarecrow’s urging, Ozma still steadfastly refuses to fight. The explanation is no longer that Oz is too weak but that killing is unethical:

“No one has the right to destroy any living creatures, however evil they may be, or to hurt them or make them unhappy. I will not fight—even to save my kingdom.”

“The Nome King is not so particular,” remarked the Scarecrow. “He intends to destroy us all and ruin our beautiful country.”

“Because the Nome King intends to do evil is no excuse for my doing the same,” said Ozma (268).

This is a touching and admirable, if foolish, dedication to principle. Or it would be, but why is Ozma determined to save the murderous slavers when she was so eager to kill Dorothy’s pet cat a couple books ago? Is Ozma aware of how many Mangaboos her friend the Wizard personally killed? Does she realize the Wizard also might be responsible for complete genocide in the Gargoyle Country? And these merciful principles are easy for her to cling to with the Wicked Witches and the giant spider already dead and gone (save Mombi), so she could just waltz in and rule without having to worry about them. Maybe she’ll change her mind when a Phanfasm seizes her.

When Dorothy, always more practical, proposes Ozma use the Magic Belt to escape to Kansas (which hilariously the Shaggy Man calls a “country”), she refuses on sturdier moral grounds: “Never will I desert my people and leave them to so cruel a fate. I will use the Magic Belt to send the rest of you to Kansas, if you wish, but if my beloved country must be destroyed and my people enslaved I will remain and share their fate” (269). Dorothy does not want to flee either, also having responsibilities as a Princess of Oz, while Em declares she and Henry have spent her life slaves anyway and choose to stay as well. (Quite a way for Em to put it when she was probably alive during American chattel slavery!)

At risk of lingering too long on this scene, the characters’ innocence is touching and tragic. Ozma suggests if she is there to meet the Phanfasms, who have already literally, physically stolen the Nome King’s throne and demanded to lead the charge, she “will speak to them pleasantly and perhaps they won’t be so very bad, after all” (270). Jack Pumpkinhead suggests they just offer the invaders “a lot of emeralds and gold,” since nobody in Oz values jewels or precious metals highly because of their abundance there (268).

Given the enormous power of the Magic Belt, it seems confusing that Ozma is not using its power to warp as many Ozites as possible to someplace safe. While the lands immediately outside of Oz are clearly hostile, surely one of the various fairy countries shown in The Road to Oz would be welcoming to them—why not send all the people she can to Santa Claus? Because Baum forgot about that, and this is more dramatic.

Stranger is that nobody suggests Ozma use the Magic Belt (or her “fairy wand,” which the Nome King is also wary of) to simply instantly warp the invading warriors back to their homelands. In this case, the claim cannot be the Magic Belt simply does not have that power or that Baum forgot or ignores it: this idea is already present in the book. Guph (since the Nome King has lost his capacity for complex thought if he was ever more than a dunderhead) advises the Nome King use the Magic Belt to warp the treacherous Whimsies, Growleywogs, and Phanfasms back to their own countries before they turn on him (277). This again shows that Baum made the Magic Belt much too powerful—he only finds drama by ignoring it.

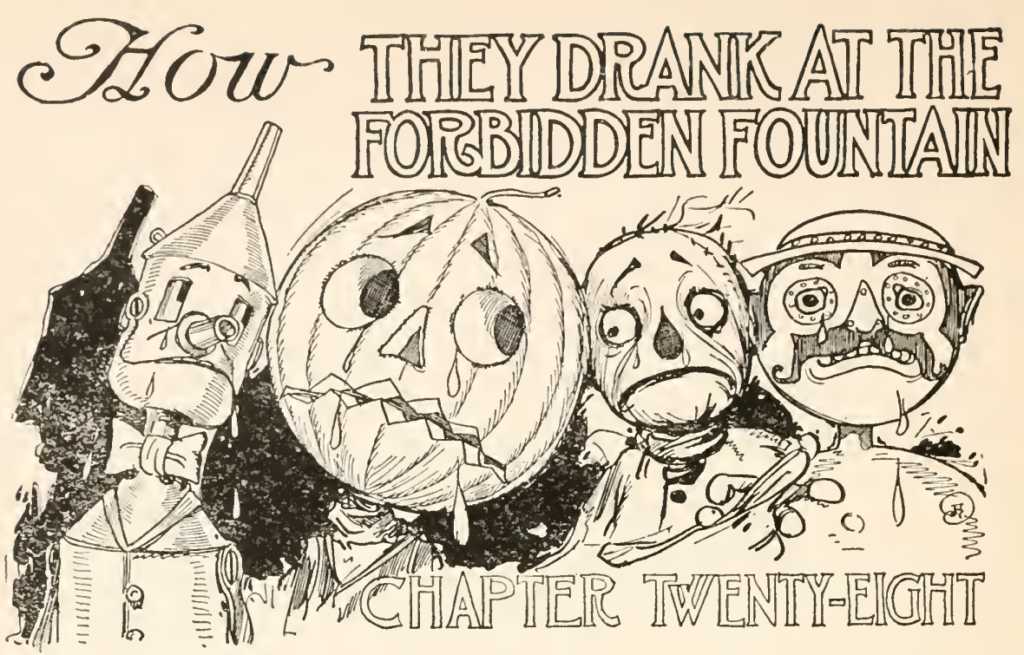

Instead, while the others grieve and Dorothy can’t sleep from fear, the Scarecrow, no longer just the smart one but “the wisest man in Oz,” devises a way to defeat the Nome King’s legions without the need to kill anyone. To this end, Ozma uses the Magic Belt to fill the Nomes’ tunnel with choking dust so that, in the morning, the evil powers all emerge desperately parched. By coincidence, they dug the tunnel so that they will enter the palace courtyard just beside the Forbidden Fountain, and when they see the water, they will rush to slake their thirst. Not mentioned prior to The Emerald City as far as I remember, the Forbidden Fountain is another of Glinda’s creations. It contains magic water that erases people’s memories. Those who drink this Water of Oblivion become “as ignorant as a baby” (271). Does it have some relationship to the Truth Pond? In the past, a wicked ruler of Oz drank from the fountain and then, having a chance to be reeducated from scratch, learned to be good. The Scarecrow hopes the same will happen if the invaders drink the Water of Oblivion. This idea of erasing someone’s identity is horrifying and despicable and perhaps more cruel and alarming than physical violence, but it is an intriguing fantasy that raises questions of nature versus nurture. (Baum comes down on the nature side, sadly, since he has the Nome King return to his evil ways in later books, but that is probably an unintentional side effect of continuing a series he had met to end.)

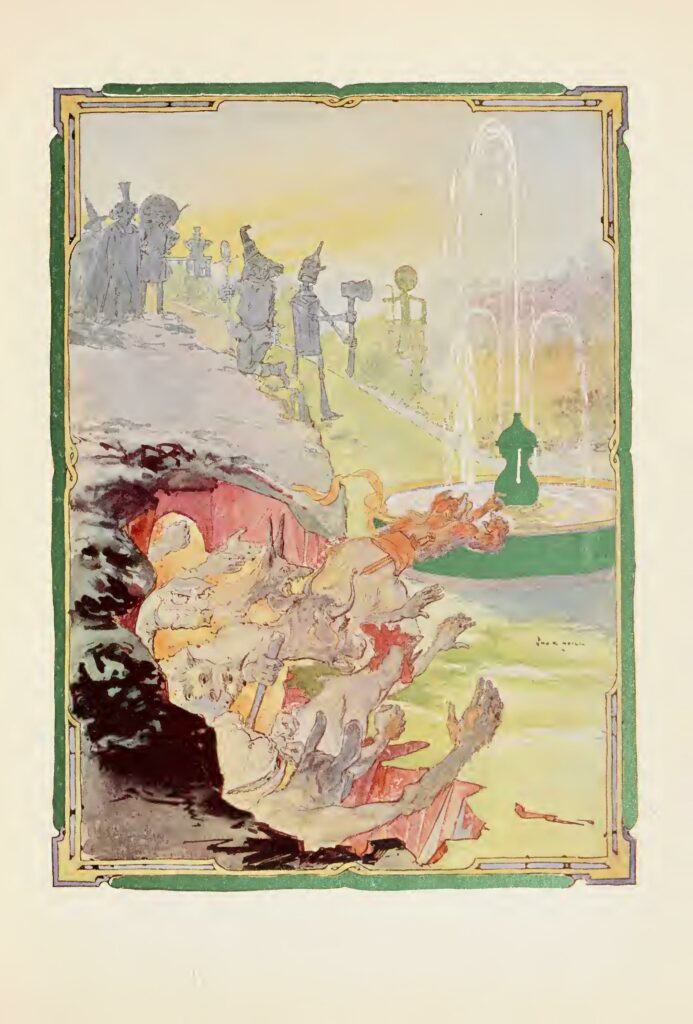

Dorothy and her friends and family watch the monsters pour out of the tunnel and drink greedily of the water. I recall a photo I have seen online of swarming centipedes drinking from a dish on a Chinese farm. The Phanfasms, then the Growleywogs, and then the Whimsies shove each other aside to reach the water, one after another, until “the great warriors [become] like little children” (283) and look on their surroundings with appreciation instead of hatred. Only the Nome King himself realizes the trick when even Guph doesn’t recognize him. “The sight of General Guph babbling like a happy child and playing with his hands in the cool waters of the fountain astonished and maddened Red Roquat” (284). Before the Nome King can command his Nome army to charge, the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman grab him and toss him into the water. When the Shaggy Man fishes the Nome King out, “he chatted and laughed and wanted to drink more of the water. No thought of injuring any person was now on his mind” (285). Ozma, though an actual child, speaks to the old Nome King like a parent, informs him of his name and that he rules the Nomes, and sends him and his army back into the tunnels to return to “the pretty cavern” of their home (286). Then Ozma uses the Magic Belt to send all the other formerly evil warriors back to their homelands.

You may be thinking this ending seems weird or wonder why I am skipping over some of the ideas in this novel. I am holding my tongue to address that in “The Politics of Oz.”

With the day saved, the characters express concern over how outsiders may imperil Oz again. Earlier in the novel, the Wizard mentions that with airships and airplanes, the Deadly Desert might no longer protect the country. “I hate those things, Dorothy,” the randomly luddite Wizard says, adding, “It wouldn’t do at all, you know, for the Emerald City to become a way-station on an airship line” (229–230). Why not? He even says he wants to contrive a magic spell that will prevent airship pilots from ever being able to reach their intended destinations—I should mention that, under Glinda’s tutelage, the Wizard has now learned real magic. The Wizard’s suspicion of outsiders arriving in airships seems like projection. Ozma also worries about airships, “for if the earth folk learn how to manage them we would be overrun with visitors who would ruin our lovely, secluded fairyland” (290). To prevent this, Glinda casts a spell that hides Oz from the rest of the world, such that it appears to just be more of the Deadly Desert. As for the Nomes’ tunnel, Ozma seals it with the power of the Magic Belt. This nightmarish isolationism, especially given how open Oz was to visitors in the last book, is another odd choice.

And of course Glinda did it. Glinda has shifted from a friendly leader of her own country with some shady connections to instead be God, except as your mom instead of your dad. Her magic resolves every issue. So far, one way or another, she pops up out of nowhere to fix every problem in every installment as of The Patchwork Girl of Oz with the sole exception of Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz. The book of information Glinda attained from her spies in The Marvelous Land of Oz, creating a more colorful and fun setting, is now a magic book in which every event in the world is documented as it happens (292). Baum has made Glinda omniscient and, through the vagueness but incredible power of her magic, omnipotent.

This enchanted severance from the rest of the world has disturbing implications. Will life really be good if nobody ages, for eternity, totally isolated from all art and cultural developments everywhere else on Earth? If Oz is a land of tolerance, how can they implicitly reject all outsiders, especially after most outsiders (Dorothy, Tiktok, Billina, the Wizard, and all the dozens of guests in The Road to Oz) are so beloved? Is Oz actually good to deny everyone else in the world their immense material wealth and magic? That sounds a bit like the issue in Black Panther. Later books establish that, within Oz, it becomes impossible to see anything beyond the country, so everyone there is just trapped forever under the totalitarian surveillance state of Ozma (which Baum establishes, in The Patchwork Girl of Oz, even bans and burns certain books).

But the real purpose of Oz’s magical isolationism is to unshackle the author from writing this stuff. L. Frank Baum incorporates himself as a character within the fiction. He is the Royal Historian of Oz who has, apparently, been creating these books because someone from Oz has informed him of what goes on there. But in the last chapter, titled “How the Story of Oz Came to an End,” he receives a note written on a stork feather:

“You will never hear anything more about Oz, because we are now cut off forever from all the rest of the world. But Toto and I will always love you and all the other children who love us.

“Dorothy Gale” (295).

Then Baum says we have had plenty of Oz anyway (he is so burnt out) and wishes Dorothy luck. Neill closes the series with Dorothy, holding (HER GIRLFRIEND) Ozma’s hand, waving a handkerchief goodbye under the words THE END. Behind them, the Wonderful Wizard sits under a tree, reminding readers of where the series began. A touching goodbye from our friend Dorothy, safe with her family in an otherworld paradise. So The Emerald City of Oz turns out a farewell after all, but a happy one.

This is a disappointing finale. The last-minute introduction of a new magical idea that solves every problem is hugely underwhelming (though typical for Glinda, a plot contrivance more than a character). Worse, our main character Dorothy has nothing to do with how the Nome King is defeated. While I dislike that in Ozma of Oz Billina outwits the Nome King on her own with no input from anyone else, at least there Dorothy does participate in his game and wins. In The Emerald City, Dorothy and most of the other characters are totally extraneous. A much more satisfying conclusion might have all the characters play a small role in defeating the Nome King using their unique talents, perhaps in a sort of Rube Goldberg machine magic spell, or just have them cooperate to deceive the foolish, greedy Nome King by using the villains’ character flaws against them. Imagine the wily Wizard running a con that tricks the Nome King!

One also wonders why Glinda is not involved in the main conflict, only popping up afterward to say she already knows everything. In The Marvelous Land of Oz, Glinda shows herself entirely willing to kill people and commands a large army. Ozma is a figurehead—Glinda is the real power defending Oz, doing all the dirty work while the little girl make-believes she is a ruler. In The Emerald City, Baum even writes in a plot hole by giving Glinda the Magic Book that surely informs her of the Nome King’s scheme, information she apparently ignores. If Glinda arrived in the Emerald City, there could even, for the first time ever, be an interesting conflict between her and Ozma’s ideas of goodness and right and wrong, certainly a better use of pages and a more resonant, meaningful conclusion than the tiring jokes that comprise most of the book.

What actually happens instead is that the Ozite characters all gather around in the twilit courtyard to idly watch the invaders. Worse than the above criticism is that the Dorothy plot basically has nothing to do with the Nome plot. What purpose does the tour of Oz or Henry and Em settling in serve in relation to the Nome King’s invasion? The cruelty of the fairy lands outside Oz parallels the cruelty of the “real world” even farther away, but this thread is too tenuous to form a strong metaphor.