After a battle against the Nome army, Ozma, Dorothy, Billina, and the rest of the crew, including all twenty-seven soldiers, escape by exploiting the Nomes’ weakness: eggs. “Don’t you know that eggs are poison?” (207). More specifically, the Scarecrow chucks an egg into both of the Nome King’s eyes, which would also work on me even though eggs are not poison to humans. With features like this, Baum maintains a sense of humor despite how frightening the situation becomes, as well as just his typical gags: “When the bell rang a second time the King shouted angrily, ‘Smudge and blazes!’ and at a third ring he screamed in fury, ‘Hippikaloric!’ which must be a dreadful word because we don’t know what it means” (226–227).

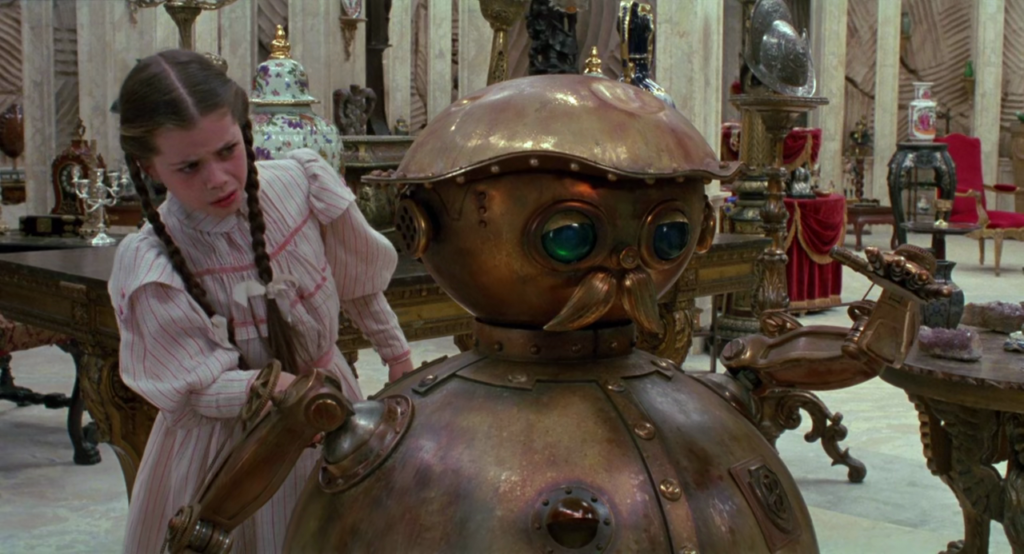

The Nome King is not, however, as scary as he is in Return to Oz. A single egg also has a rather more dramatic effect on him there than multiple do in the novel.

Ozma of Oz concludes with Dorothy returning to Oz with all her friends, including Tiktok and Billina, where she spends “several very happy weeks” (263). The Nome King is last seen on page 254, waving his fist at Ozma’s entourage as they cross the Deadly Desert back to their homeland. Dorothy catches up with all the characters—except Mombi, since who cares about her. The Woggle-Bug is apparently the president of the new College of Art and Athletic Perfection, and Jinjur is happily married to a man she abuses.

At last, learning that Uncle Henry is alone in Australia, grieving his niece, Dorothy returns home using the power of the magic belt she stole from the Nome King. However, she does not repeat her mistake with the silver slippers from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. This time, so that the belt can retain magical potency, Dorothy leaves it with Ozma, who will use the belt’s power to check on Dorothy every Saturday and instantly warp her back to Oz in response to “a certain signal” (267).

While it is an enjoyable read, Ozma of Oz is less effective emotionally than Return to Oz. There are two reasons for this.

The first is that the Oz novels, at least thus far, are just not very emotional. The characters rarely seem to particularly care about what is going on or the peril that they are in. This may make the stories less distressing to children, but this also renders allegedly happy or triumphant moments underwhelming, because there was no sense of adversity or sadness to compare them with. Baum does emphasize that Dorothy is “trying to be brave in spite of her fears” (199), but this only occasionally comes through. Rather than saddened or distressed over her plight when facing the Nome King, Dorothy seems how almost all Baum’s characters usually seem, lackadaisical or even slow-witted: “Dear me! I wonder if Uncle Henry or Aunt Em will ever know I have become an orn’ment in the Nome King’s palace, and must stand forever and ever in one place and look pretty—’cept when I’m moved to be dusted. It isn’t the way I thought I’d turn out, at all; but I s’pose it can’t be helped” (200–201). It is difficult for a reader to care about characters who do not seem to care much about themselves or each other.

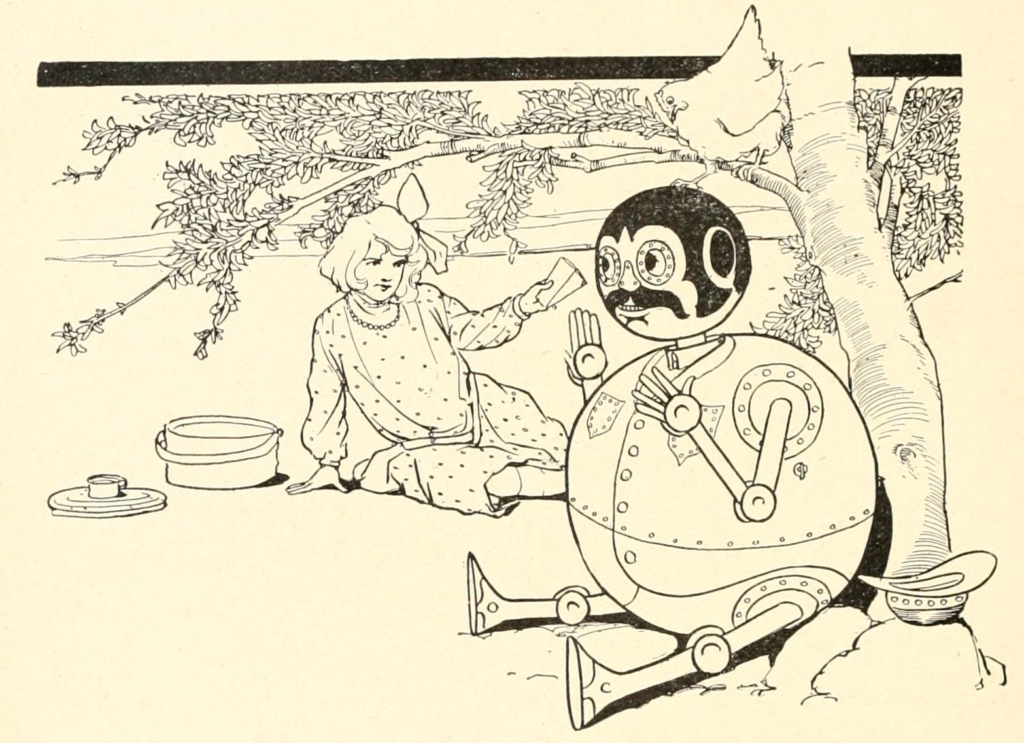

Compare Dorothy and Tiktok’s relationship in Ozma of Oz to their relationship in Return to Oz. In Ozma of Oz, Tiktok considers himself Dorothy’s slave: “I am the slave of the girl Dor-oth-y, who rescued me from pris-on” (132). Later, in the Nome King’s palace itself, Tiktok insists he has to make his guesses before Dorothy because “the slave should face danger before the mistress” (196). Dorothy never seems to particularly care about Tiktok one way or another. The climactic scene for their relationship occurs when Tiktok stops functioning before making his final guess inside the Nome King’s palace, so the Nome King sends Dorothy in to wind him up (Tiktok is a clockwork robot and hence relies on three keys being fully wound to think, move, and talk). When she finds him, Dorothy winds up Tiktok, who wishes he was better at guessing. Both seem rather sad, according to the narration (Dorothy speaks “sadly”), but Dorothy tells him, “if you fail I will watch and see what shape you are changed into” (200). Tiktok then touches a yellow glass vase, says “Ev,” and vanishes, Dorothy unable to see what the Nome King turned him into. Instead of hopeless, though, she barely seems to care, like she is on sedatives and cannot think properly.

In Return to Oz, meanwhile, Tiktok is Dorothy’s friend, not slave, whom the Scarecrow left to protect her if she returned. It helps that Dorothy is still a simple country girl, instead of the Neill Dorothy who appears to be an aspiring model. Their mutual concern for each other seems more believable in part because Tiktok and Dorothy are allowed more interactions, and in part because Tiktok seems essential to protect her in the dangerous Oz of the film. In Ozma of Oz, the titular princess/queen turns up with many other whimsical characters so that instead Tiktok rapidly recedes into the background. And consider Tiktok’s scene in the Nome King’s palace. In Return to Oz, this is Dorothy’s final temptation by the Nome King, who offers to spare her and send her back to Kansas. Going in after Tiktok is a selfless, courageous deed. Then Dorothy discovers that Tiktok is already wound up.

“It was my way of getting you in here,” says the movie’s Tiktok. “Pretend that you are winding me up anyway. I have an idea that may save us. I have one guess left, and if I guess incorrectly, you can watch and see what I am changed into. That may give you a clue.” This is much more interesting: Tiktok is being clever, tricking the Nome King, and trying to help his friend, knowing that he himself will likely fail to guess correctly. Dorothy and Tiktok seem to genuinely care for each other here: Dorothy hugs Tiktok goodbye, and Tiktok, in a moment that might be a bit overboard but I love anyway, cries what looks like windshield wiper fluid. In comparison, in Ozma of Oz, Dorothy and Tiktok seem like clueless doofuses (Dorothy survives literally by a lucky guess, though unfortunately that also happens in the movie), and Dorothy does not seem to waste time feeling sorry for her self-identified slave.