In addition, Tip raises some troubling questions in the way he uses the magic powder to bring life to various beings. To begin with, he steals it from Mombi, who though cruel is a poor old woman who has just purchased it. Whereas before Baum could allow the Scarecrow to be a living being with no explanation, now Baum considers in detail what it means for Jack Pumpkinhead, the Saw-Horse, and the Gump to spring to life and explores the implications of their existence. There is discussion of their inability to eat and feel physical sensations and the uncertainty of their continued survival. Tip never seems particularly concerned.

The Gump, also called the Thing, is particularly disturbing: it is the severed head of an elk-like animal mounted on the wall and then brought back to life with a body made out of two couches, a broom, palm leaves, and some string. The animal is conscious that it used to be alive before a hunter suddenly shot it and finds its new condition bleak and hopeless. In the ending, its only wish is to die: “I did not wish to be brought to life, and I am greatly ashamed of my conglomerate personality. Once I was a monarch of the forest, as my antlers fully prove; but now, in my present upholstered condition of servitude, I am compelled to fly through the air—my legs being of no use to me whatever. Therefore I beg to be dispersed” (284). However, though they disassemble his body, the characters prove unable to return this tortured animal to the grave. This is what the “good guys” do? It is not that they are villainous or cruel, but they seem somehow less than heroic.

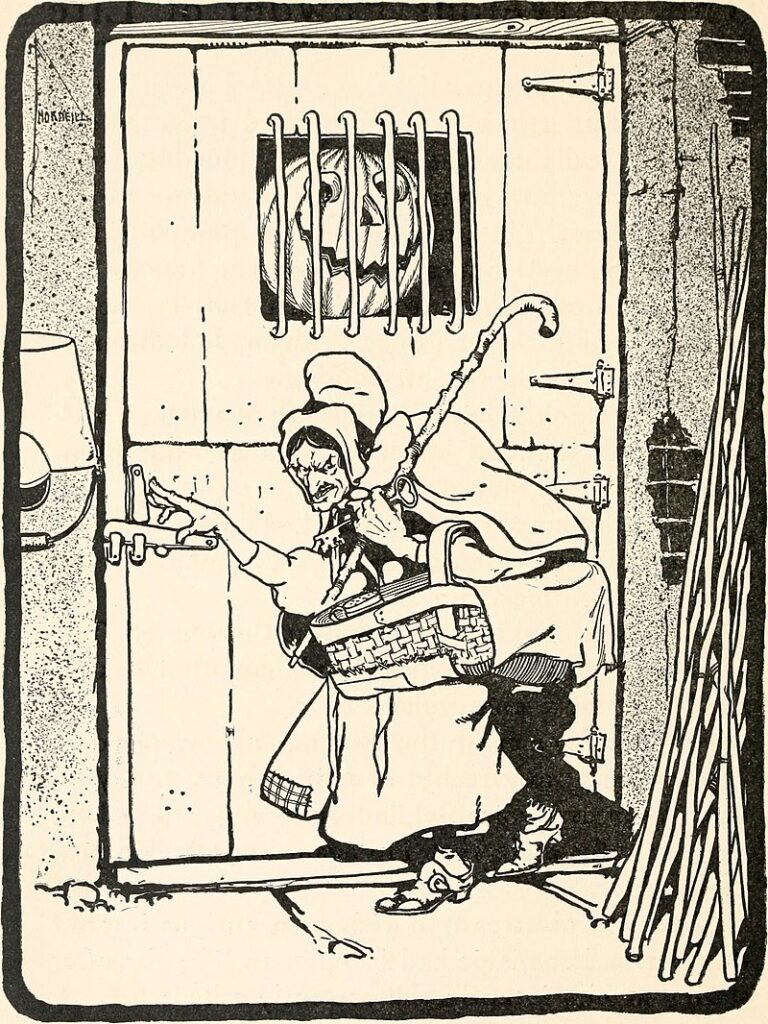

Mombi and General Jinjur make for somewhat strange villains themselves. Physically, the Wicked Witch of the 1939 movie, with her dark robes, hat, stature, and pointed noise and chin, seems to be based more on Mombi than Baum and Denslow’s one-eyed queen of the Country of the Winkies. But unlike that witch, Mombi is a pivotal ally of the Wonderful Wizard. This introduces moral gray because the Wizard, while a conman and liar, is generally friendly in the book that bears his name. And unlike either interpretation of the Wicked Witch of the West, Baum describes Mombi with a degree of ambiguity:

“[T]he Gillikin people had reason to suspect her of indulging in magical arts, and therefore hesitated to associate with her” (7).

“Mombi’s curious magic often frightened her neighbors, and they treated her shyly, yet respectfully, because of her weird powers. But yet Tip frankly hated her, and took no pains to hide his feelings. Indeed, he sometimes showed less respect for the old woman than he should have done, considering she was his guardian” (9).

Not a vicious dictator, Mombi is a strange, isolated old woman who lives in a farmhouse. Unlike last time, the dictators are the heroes. While Mombi is cruel to Tip, he gives it as good as he takes. The dynamic is totally different from the Wicked Witch, a tyrant who enslaves Dorothy and her friends. Baum also allows Mombi to display sincere, endearing joy over her magic, and he revels in describing the wonderful liberation of her transformative powers, which allow her to switch from old woman to little girl to rose to shadow to ant to griffin. (It reminds me of a scene of even more bonkers transformations from the One Thousand and One Nights.)

Despite Mombi’s general nastiness, I felt sorry for her when Glinda gives her the choice to be executed or to lose all her magic forever. “Then I would become a helpless old woman!” says Mombi (268). I wanted Mombi to escape! I wanted to cheer for this modest rogue, against the lawful good sociopath ultra-rich queen Glinda who sits around on a golden throne and hates transformations. In contrast, the Wicked Witch of the West had her death coming and completely earned her title (at least in Baum’s version of the story). Baum agrees, at least to the extent that Mombi both survives and apparently receives a stipend to live on from Queen Ozma.

(The Mombi in Return to Oz is largely based on Langwidere from the third Oz novel, Ozma of Oz.)