General Jinjur and the Army of Revolt are the most overtly political aspect of the plot. Jinjur is a beautiful young girl—young enough that she is living with her mother doing chores, anyway—who unites the women of all the countries of Oz to overthrow the Scarecrow.

“May I ask why you wish to conquer His Majesty the Scarecrow?” Tip asks her. She responds, “Because the Emerald City has been ruled by men long enough, for one reason[. …] Moreover, the City glitters with beautiful gems, which might far better be used for rings, bracelets and necklaces; and there is enough money in the King’s treasury to buy every girl in our Army a dozen new gowns. So we intend to conquer the City and run the government to suit ourselves” (86–87).

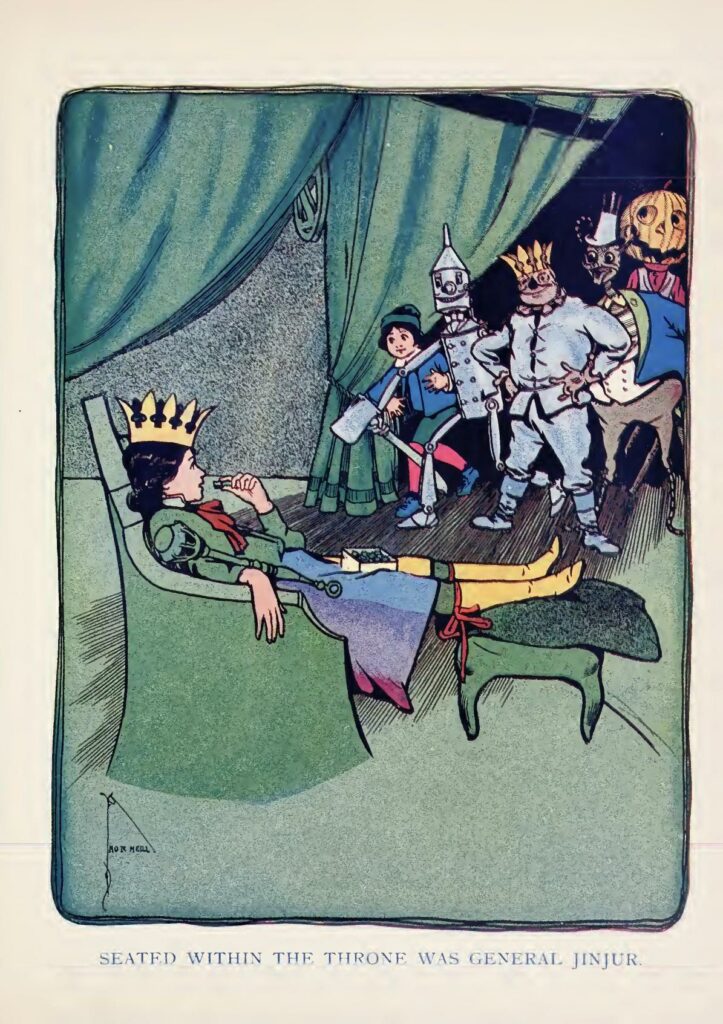

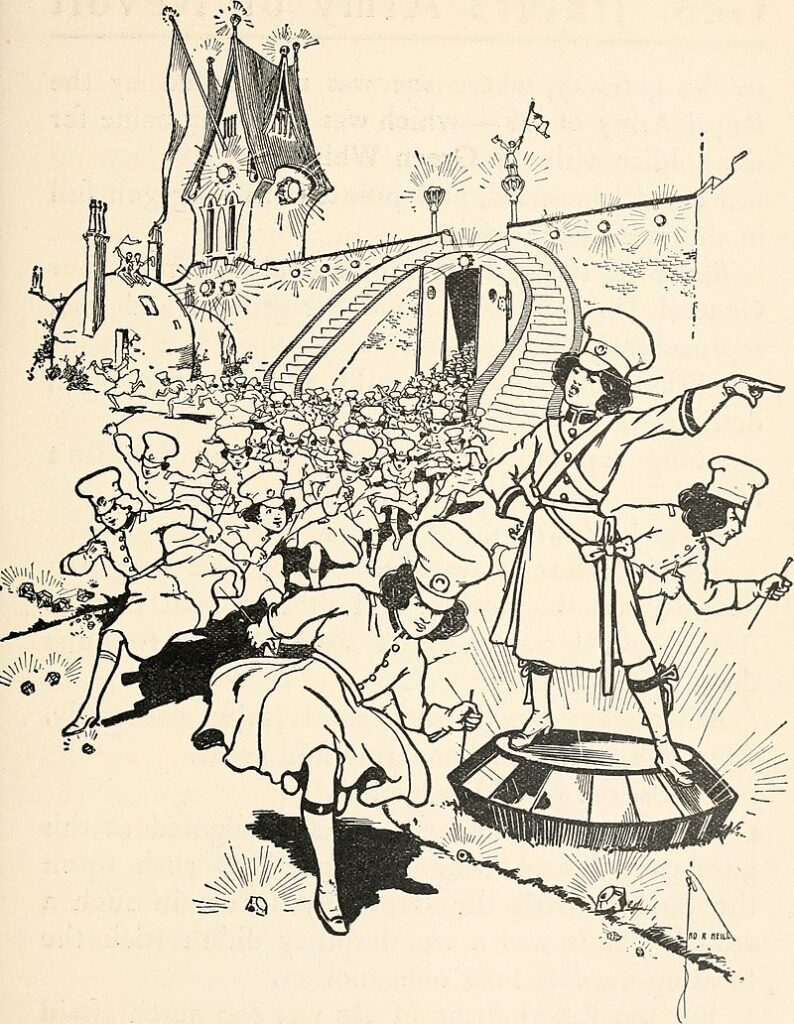

From the start, Baum employs various sexist tropes with Jinjur and her forces. They are totally frivolous, treating war as a game. Their weapons are knitting needles, they do not know how to govern, and their main motive is that they are lazy, want jewelry and new clothes, and want to sit around eating sweets all day. The text emphasizes that the women are pretty, so men will never hurt them (if only that were all it took), giving them an advantage. When the army surrounds Tip and his friends, the Scarecrow temporarily drives them away by sending mice running at them, mice being something that all women are terrified of, as we all know. After Tip, the Scarecrow, Jack, and the Saw-Horse escape the Emerald City the first time and return with the Tin Woodman, they discover that gender roles have been inverted so that the men are stuck doing domestic labor while the women sit around idly chatting. The claim that men have run the Emerald City for too long is only a pretext. Jinjur reveals her true motive in counsel with Mombi: “[I]t is so aristocratic to be a Queen that I do not wish to be obliged to return home again, to make beds and wash dishes for my mother” (251).

Jinjur and her army are a teasing caricature of feminists and the suffragette movement gaining momentum in Baum’s day. Because treating women as humans was so unthinkably shocking to insecure dunderheads, conservatives at the time would caricature feminists as seeking a world where women took men’s roles (such as having lives, I suppose), and men were stuck in women’s (implicitly acknowledging that women had a raw deal). Baum directly copies this. Most insulting of all is the equation of women seeking rights with whiny, incompetent children demanding they be allowed to eat fudge all day. In the end, upon Jinjur’s defeat, even the women rejoice because they secretly want to be domestic servants: “At once the men of the Emerald City cast off their aprons. And it is said that the women were so tired eating of their husbands’ cooking that they all hailed the conquest of Jinjur with joy. Certain it is that, rushing one and all to the kitchens of their houses, the good wives prepared so delicious a feast for the weary men that harmony was immediately restored in every family” (283).

However, General Jinjur is by no means evil, despite proving a capable opponent. In her first scene, she gives food to the starving Tip, hardly a villainous act. The text enjoys the glamor of her dress and boldness. While, beside Mombi, it is clear that she is a girl in over her head, Jinjur also disproves reductive stereotypes through her own bravery, ability to organize the Army of Revolt, and success at overthrowing the men. Even in his anti-feminist mockery, Baum acknowledges that women’s work is tough. “I’m glad you have decided to come back and restore order,” says one of the men doing domestic labor, “for doing housework and minding the children is wearing out the strength of every man in the Emerald City.” The brainy Scarecrow answers, “If it is such hard work as you say, how did the women manage it so easily?” The husband is left to suggest women are made of cast-iron (170–171). Baum also avoids the cruelest misogyny of contemporary conservative caricature that imagined feminists as hateful, “ugly” spinsters because The Marvelous Land portrays the Army of Revolt and their leader as young women so beautiful and whimsically fun that Baum and Neill seem to adore them.

Baum further disproves this reductive sexism by having Jinjur lose not to the male hero or any of his male friends but to Queen Ozma. The Army of Revolt loses to Glinda’s army, which is also comprised entirely of women but is portrayed as competent and able without any irony: “But these soldiers of the great Sorceress [Glinda] were entirely different from those of Jinjur’s Army of Revolt, although they were likewise girls. For Glinda’s soldiers wore neat uniforms and bore swords and spears; and they marched with a skill and precision that proved them well trained in the arts of war” (237).