Nome Plot

The Emerald City features two plotlines that intersect near the end. In the first of these, focused on in six of the 30 chapters before overlapping with Dorothy’s plot beginning in Chapter 24, the diabolical Nome King returns. Last seen in Ozma of Oz shaking his fist at Ozma’s procession crossing the Deadly Desert, he has become deranged in his obsession with vengeance for the theft of his Magic Belt and the liberation of his slaves. The Nome King is no longer named Roquat of the Rocks but instead Roquat the Red, presumably because he is so full of rage he screams until he turns red. “The reason most people are bad is because they do not try to be good. Now, the Nome King had never tried to be good, so he was very bad indeed” (39). As Neill draws him, the Nome King’s hair has also grown so much longer that it drags behind the ironically egg-shaped fiend.

The first chapter focuses on the Nome King rather than Dorothy, establishing narrative suspense. Baum layers on the buildup: “The Nome King could not forgive Dorothy or Princess Ozma, and he had determined to be revenged upon them. But they, for their part, did not know they had so dangerous an enemy. […] An unsuspected enemy is doubly dangerous” (20). The Nome King is a brutal antagonist, though no longer in so memorably unique a way as in Ozma of Oz (or Return to Oz). He evaluates the number of slaves he will be able to take from Oz, makes clear his objective is complete genocide; yells at, beats, and “throws away” his minions; and is generally a ruthless, emotionally unstable militaristic dictator. Like Darth Vader, the Nome King has a habit of killing his direct subordinates when they displease him, though continues feigning politeness:

“Will you do this, General Crinkle?”

“No, your Majesty,” replied the Nome; “for it can’t be done.”

“Oh, indeed!” exclaimed the King. Then he turned to his servants and said: “Please take General Crinkle to the torture chamber. There you will kindly slice him into thin slices. Afterward you may feed him to the seven-headed dogs” (41).

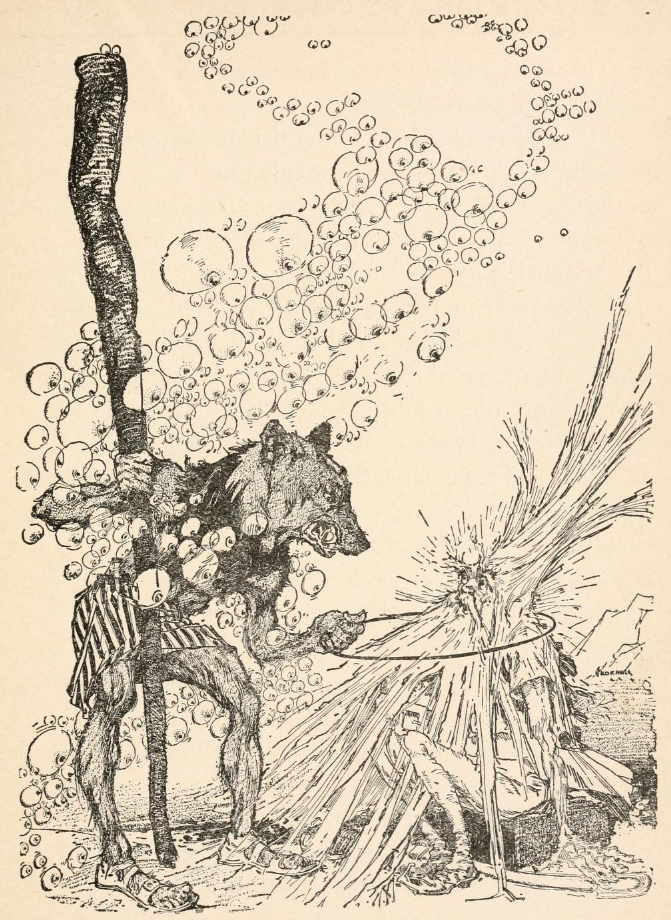

Though highly dangerous, the Nome King has become buffoonish, more like a pouting child than the terrifying sorcerer in Ozma of Oz. The brains of the operation are Guph, a particularly crafty Nome who volunteers to be General even though the Nome King has executed his predecessors. As he tells his sovereign, Guph is the only Nome who can defeat Oz, steal its vast riches, kill and enslave its people, and retrieve the Magic Belt from Ozma. This is why Guph dares disrespect the Nome King: “You want to conquer the Emerald City, and I’m the only Nome in all your dominions who can conquer it. So you will be very careful not to hurt me until I have carried out your wishes” (44). Neill draws Guph with a flower in his hair, probably because it is otherwise difficult to distinguish him from the Nome King. There is a sense to the design since flowers grow from underground, and the Nomes rule the underground.

The Nomes will dig a tunnel under the Deadly Desert, like the tunnel that appears in Return to Oz, and erupt into the Emerald City to take the Ozites by surprise. Contrary to the Nomes’ steamroller victory in the movie, however, Guph warns the Nome King that they cannot simply storm into the Emerald City. Ozma’s magic is too powerful, and with Billina and her numerous offspring, the Ozites have an ample supply of eggs, which all Nomes fear. (Billina has many chicks who are attending the Woggle-Bug’s university, but she is happy to give away her unfertilized eggs for others to eat. I have no idea who the father is because there were previously no chickens in Oz.) Furthermore, the Nomes cannot send raptors to kill the chickens because Oz’s birds are protected by magic (145).

Guph explains, “There are a good many evil creatures who have magic powers sufficient to destroy and conquer the Land of Oz. We will get them on our side, band them all together, and then take Ozma and her people by surprise” (46). Though failure means the Nome King will kill him, assuming the “evil creatures” do not, Guph accepts the risk because “[h]e hated every one who was good and longed to make all who were happy unhappy. Therefore he had accepted this dangerous position as General quite willingly, feeling sure in his evil mind that he would be able to do a lot of mischief and finally conquer the Land of Oz” (59). Guph just loves his job!

While the Nomes dig the tunnel, Guph spends three chapters traveling the lands east of the Deadly Desert to enlist the aid of three tribes of “evil spirits”: the Whimsies, the Growleywogs, and the dreaded Phanfasms. The Phanfasms are “Erbs” (115), “the most powerful and merciless of all the evil spirits” (126), an odd bit of worldbuilding that I doubt Baum ever again returned to. In establishing these new characters, the travelogue of the Nome chapters shows a great scoop of creativity. Guph faces enough peril and shows enough cunning to earn the reader’s sympathy, including undergoing needle-based torture by the Growleywogs. Even the ever-moralizing narration can’t quite dislike Guph: “This Guph was really a clever rascal, and it seems a pity he was so bad, for in a good cause he might have accomplished much” (118).

The recruitment proceeds along gradations of power, with the Whimsies the weakest and, in their way, kindest of the “evil powers” and the Phanfasms by far the most strong and wicked. Guph wins the Whimsies and Growleywogs over by offering them slaves, jewels, and other physical results of conquest, for “[p]eople often do a good deed without hope of reward, but for an evil deed they always demand payment” (63). (The Whimsies do not actually seem particularly evil, being hospitable to Guph and disinterested in hurting Ozma.) But the Phanfasms, living for centuries in isolation on the feared mountain Phantastico, are already more rich and powerful than Ozma. Terrified to meet the Phanfasms after evading the mountain guardian, Guph is rapidly captured and dragged to a series of crude stone huts. Guph’s meeting with and attempts to bluff the Phanfasm leader, the First and Foremost, is riveting dark fantasy:

With all his knowledge and bravery General Guph did not know that the steady glare from the bear eyes [of the First and Foremost] was reading his inmost thoughts as surely as if they had been put into words. He did not know that these despised rock heaps of the Phanfasms were merely deceptions to his own eyes, nor could he guess that he was standing in the midst of one of the most splendid and luxurious cities ever built by magic power. All that he saw was a barren waste of rock heaps, a hairy man with an owl’s head and another with a bear’s head. The sorcery of the Phanfasms permitted him to see no more (120).

Before the swarming, shapeshifting Phanfasms kill him (the First and Foremost changes shape and gender), Guph is able to persuade them to assist the Nomes by offering the one thing they lack: “the exquisite joy of making the happy unhappy” (125). The Phanfasms, who would have destroyed Oz long ago if the Deadly Desert did not block them, release Guph. Here it is clear that Guph has made a disastrous mistake, awakening an ancient evil that will doom the world. “We will use King Roquat’s tunnel to conquer the Land of Oz,” says the First and Foremost. “Then we will destroy the Whimsies, the Growleywogs and the Nomes, and afterward go out to ravage and annoy and grieve the whole world” (126). In a JRPG, after the player beats the Nome King, the real final boss would be the First and Foremost. He even changes his shape, allowing for multiple phases.

The Phanfasms are not alone in their treachery. Each of the four countries of the alliance—Nomes, Whimsies, Growleywogs, and Phanfasms—are completely self-interested, smugly certain of their own power, and plotting to betray the others once they have razed Oz and taken their slaves (the Growleywogs talk ahead of time about which of them will get Tiktok as a slave, which the Scarecrow, etc.). Guph himself schemes to overthrow the Nome King after the conquest (86). Contrasted with the legions, the Nome King seems almost tender in wanting none of “those dreadful creatures” to kill or enslave Ozma and Dorothy because he wants them to be his own slaves, transformed into “china ornaments” he will be sure his maids dust carefully (146).

A stark contrast to the childlike goofs and general niceness of Dorothy’s ramblings in Oz with which they are juxtaposed, the Nome chapters feature robust dark fantasy. It is clear Baum was at his best when not writing about Oz, which he had reinterpreted by this point as a utopia on par with Heaven.