5. When We Try to Deceive People: The Totally American Fantasy

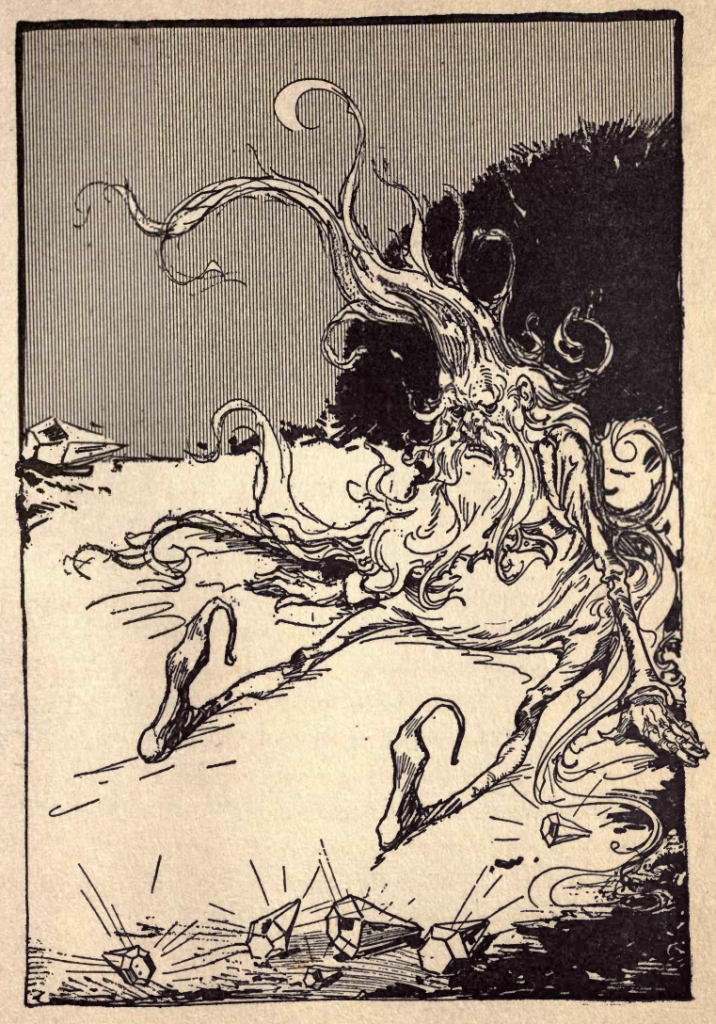

The Library of Congress has called The Wonderful Wizard of Oz “the first totally American fantasy for children.” Even this description ignores the vast number of stories told to children in Native American cultures, but “fantasy” would be a trivializing misclassification of most of these, even as “American” is, in political terms, a misclassification as well. The US tends to obscure, excuse, and deny the violence, genocide, slavery, and imperialism that are the roots of its physical territory, economy, and ideology. Its representatives often claim the US has always stood for lofty principles of democracy, human rights, and other similar good things and that its history is the realization of these values. In reality, the US has always applied these principles chiefly to small, favored groups and actively fought and destroyed them for its Indigenous and enslaved populations and at various points for other countries: Hawaii, the Philippines, Iran, Guatemala, Chile, etc. There are many Nome Kings in our world.

Baum retcons and re-retcons his fantasy utopia to erase unpleasant and awkward details of its own origins, history, double standards, and stolen wealth and magic. The resultant dishonesty costs his novels not only narrative but thematic integrity. This incoherence exposes contradictions between the civic ideology and the reality of the country in which he wrote the series, as well as in his own personal values, which at once advocated pacifism and merciless murder, that this country shaped. Especially considering that the Oz novels’ author wrote increasingly not out of passion but for mercenary reasons, it is fitting that this, of all stories, would be “the first totally American fantasy for children.” Mirroring the willful amnesia of the United States, Oz’s identity as a virtuous utopia is built on denial of its past.

Then are those who take inspiration from Oz’s stated values of peace and love, its radical economy, its surprising queerness, wrong to do so? Probably not. These themes are present. All that can be done when reading work from a long-dead author with questionable or outdated values is to consider the art through whatever lens one finds most valuable, while not neglecting to acknowledge the more unsavory aspects and consider how they affect the work and our engagement with it. And most importantly, one should also read (and uplift) work from artists who are/were not bigoted and, particularly, who are themselves members of marginalized communities.

Their gaping narrative and thematic inconsistencies mean any grand claim that extends beyond a single Oz novel can never escape contradictions. This goes for both the utopian readings and mine. In the chapter titled “Baum’s Oz: (Dys)(Eu)(U)Topia?” Tuerk puts it best: “Actually, Oz is not a totalitarian state. It is a fairyland in books for children” (191).

Whatever political concerns his ambiguous corpus might express, Baum never explored how Ozma “civilizes” the Land of Oz, “many things no one would expect her to accomplish” (Marvelous Land 285). The reader learns only of the aftermath. So, except for women’s rights, the novels avoid any practical ideological or political commitment. Instead they offer only ideals, a sacred, impossible Neverland for readers to dream about, particularly given the fixation on agelessness and eternal life that suffuses the series beginning in The Road to Oz and escalates from Tik-Tok of Oz onward. Though he did endorse the white supremacy of US empire, Baum endorsed neither democratic socialism nor communist dictatorship, nor an agrarian republic nor monarchy. For the famous description of the pastoral socialist utopia that I quoted at the start of the essay concludes with this: “I do not suppose such an arrangement would be practical with us, but Dorothy assures me it works finely with Oz people” (Emerald City 31).

By exploring Oz and unearthing the ugliness of a time when naked racism was embraced in popular entertainment, I hope I have both stirred some thoughts about how norms change and reminded us that, in the US, racists and racism are deep at the roots of many major cultural milestones. A story in this culture inevitably has the presence of race, and its literal absence still says something about the matter. The Oz series is not particularly or unusually “problematic” for a pop cultural production of its time, and I do not want to give the impression it is. Mickey Mouse displays minstrel characteristics as well. These readings, while justifiable within the text, were formed in light of the racism in Baum’s other writing and the question of how that affects his most famous work. My point is not that Baum or Oz is uniquely “bad.” Rather, I wanted to demonstrate how even a seemingly frivolous series of children’s books is political and complex and contains, for good and ill, the fingerprints of the broader culture that nurtured its author.

Let’s go read something for adults written by an Indigenous author instead, like The Names by N. Scott Momaday (beautiful!) or Red by Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas or the Penguin Classics edition of Zitkala-Ša, or Thinking in Indian by John Mohawk for those who want philosophy and politics rather than fiction or memoir.