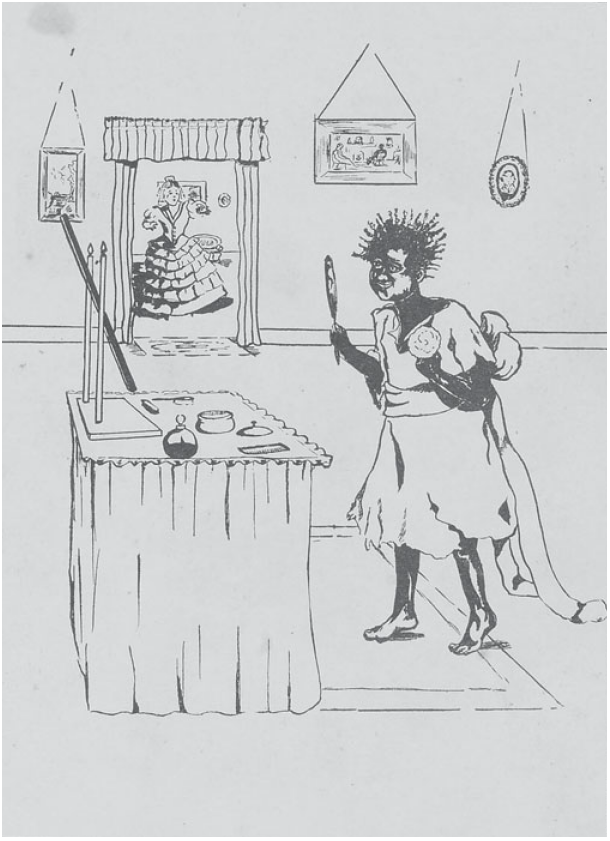

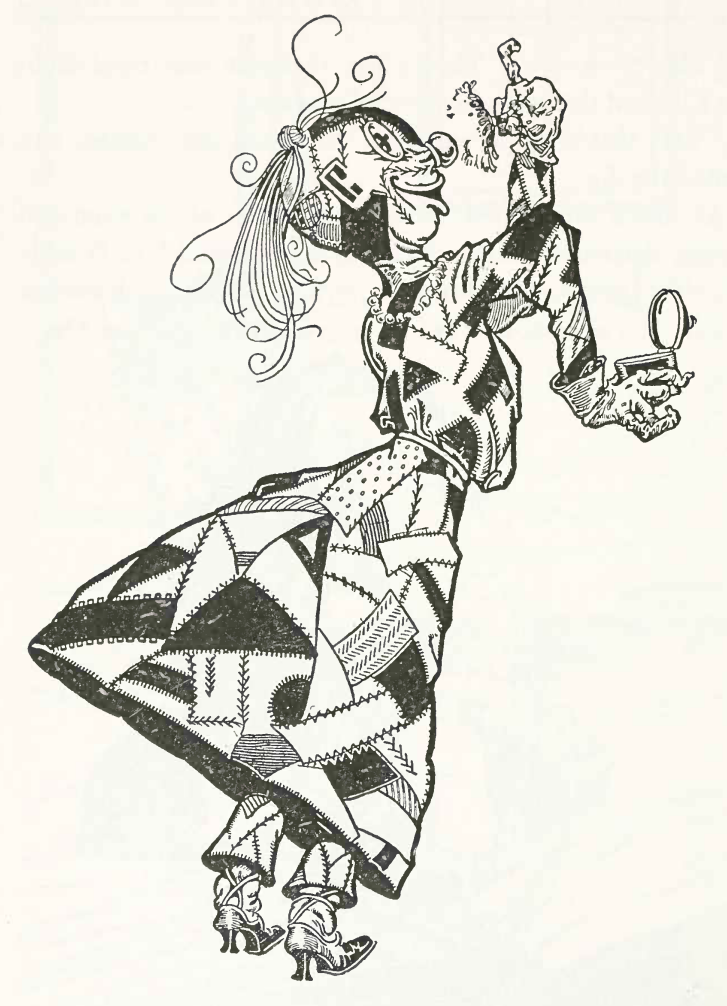

Bernstein observes that Scraps the Patchwork Girl, a particularly popular Oz character, also features various aspects of racist caricature. Although her story is one of ultimately escaping a servile position, she is a comical slave prone to silly musical numbers. The novel that introduces her even features a minstrel song about “mah coal-black Lulu” (165). Scraps engages in slapstick repartee with the Scarecrow and has large gloves, prominent lips, curly hair, and wide, circular eyes. Bernstein particularly notes an unusual illustration of Scraps with a powder puff. Never referenced in the text itself, the makeup alludes to Topsy, a character from Uncle Tom’s Cabin and, relevant here, its mocking blackface stage adaptations. Topsy “whitens up” her Black skin with a similar powder puff in iconography that would have been familiar in 1913 (169–171).

Above, left: Topsy whites up, shown in Bernstein 170. Above, right: Scraps powdering her face from Patchwork Girl 46.

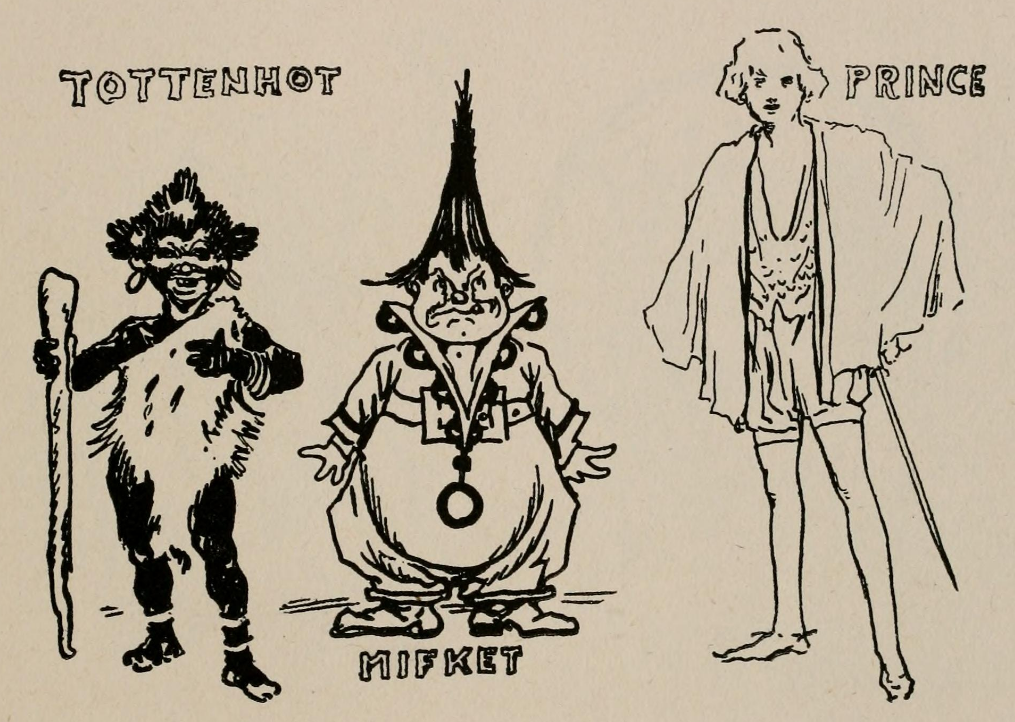

There is more overt racist caricature in The Patchwork Girl as well. Dorothy and friends meet the “Tottenhots,” curly-haired, “dusky”-skinned short people dressed in costumes of vague Indigenous stereotypes: assorted jewelry and skirts made from pelts (244). In further minstrel and general racist tropes, the Tottenhots are childish pranksters and subject the Scarecrow to slapstick mob violence. The name is derived from “Hottentot,” an offensive term then in common use for the indigenous Khoekhoe people of southern Africa.

In Rinkitink in Oz, Baum refers to Tottenhots as “a lower form of man” (294). Here there is a miniature great chain of being-style racial hierarchy of the fairylands in which the (white) human is at the top and the Tottenhot, drawn now with jet-black skin, ranks below the Mifkets, literally inhuman, furry creatures and themselves a questionable depiction of islander savages. Tottenhots are insulting caricatures of Black people and metaphysically subhuman. Michel was mistaken when he wrote that “All minorities would likely find Oz’s diversity compelling” (36).

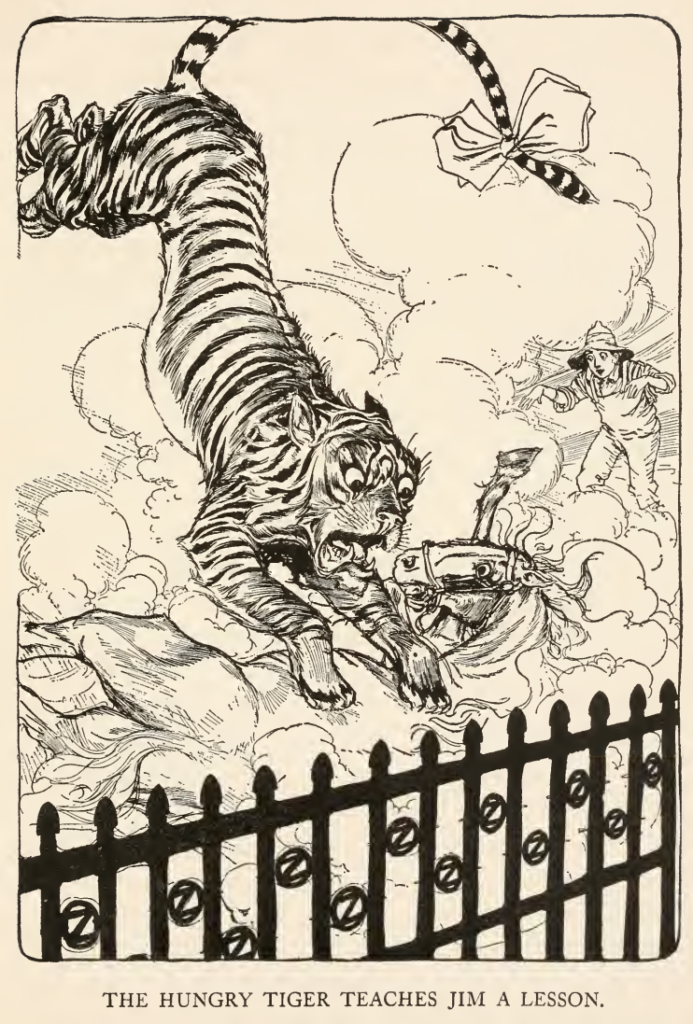

Disregarding these racist aspects, however, the Oz that Baum depicts still falls short of the ideals of inclusion and nonviolence. Who deserves compassion and tolerance and who does not is often arbitrary. The grimmest Oz book, Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, correspondingly depicts the “civilized” Oz in the bleakest terms. Dorothy’s relative Zeb and the horse Jim visit Ozma’s kingdom, and in a moment of anger, Jim kicks the indestructible Saw Horse. The Hungry Tiger promptly “[strikes] Jim full on his shoulder and [sends] the astonished cab-horse rolling over and over” while the Ozite audience cheers on the violence, craving revenge for the slight to the Saw Horse (228). The Lion and Tiger then threaten Jim, all while Ozma tacitly approves. Later, all Ozites are hostile to Eureka, Zeb, and Jim for being too like beings from the mundane world, so that all three are glad to finally leave.

And far from compassionate, Ozma, like the Nome King, amuses herself with the pain of others: “Ozma laughed as merrily at her weeping subject as she had at [Zeb]” (223). Afterward, a completely unapologetic Ozma uses her soldier Omby Amby to terrorize Dorothy to tears, treating her best friend with less patience than she does the Phanfasms, murderous slavers who announce their desire to destroy all the nations on Earth. Consider also Ozma of Oz, in which a martial Ozma threatens Langwidere: “I am powerful enough to destroy all your kingdom, if I so wish” (112).

Tik-Tok the robotic man becomes one of Oz’s most respected citizens after Dorothy rescues him in the wilderness of Ev. However, in The Road to Oz, Baum treats prejudice against Tik-Tok as reflecting the facts of life. The narration contrasts Tik-Tok with his friend the Tin Woodman, claiming, “You could love the Tin Woodman” for his kindly personality, whereas “to love such a thing as [Tik-Tok] was as impossible as to love a sewing-machine or an automobile” (170–171). Tik-Tok, however, is as capable of thought and sensation as any of the human (or fairy) characters, even having a full arc in Ozma of Oz as he realizes he was wrong to trust the Nome King just because the Metal Monarch acts within the law.