When Ozma decides to conquer the Nome Kingdom and “civilize” the neighboring country Ev, intervening not on behalf of the terrorized public but of the decadent, murderous, tyrannical royal family, she thinks nothing of Dorothy apparently killing Nome soldiers. Ozma herself is militant and open to killing. “[I]f we are obliged to fight the Nome King,” the Tin Woodman says, “every officer as well as the private, will battle fiercely unto death” (Ozma of Oz 129). Ozma is as good as her word, later commanding the small Ozite army, “Forward, my brave soldiers, and fight for your Ruler and yourselves, unto death” (232). The difference between the Nome King and Ozma is that the latter lacks as disciplined, organized, and well-equipped a military.

The “civilizing” process the Wizard personally undergoes is a journey in which he protects Dorothy until she brings him to Oz. This process itself involves killing various people and even the complete extermination of the Gargoyles, yet Ozma and Glinda welcome him into the royal court. Glinda teaches him real magic so that the Wizard becomes, effectively, a policeman enforcing the same state he used to run with fear and lies. There is no reason to suppose Ozma did not exercise similar force and violence in transforming Oz from the unstable, deadly land of the first two novels into the civilized utopian Oz.

In “Dorothy the Conqueror,” J. L. Bell argues (unsurprisingly) that Dorothy is a conqueror. Bell frames her adventures in terms of a civilizing mission, of imperialism. She kills both Wicked Witches, overthrows the Wizard, gains service from the Queen of the Field Mice and the King of the Winged Monkeys, helps slay the giant spider, terrorizes the Princess of the China Country into submission, and sees the ascension of her friends the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion into kingship over their own countries.

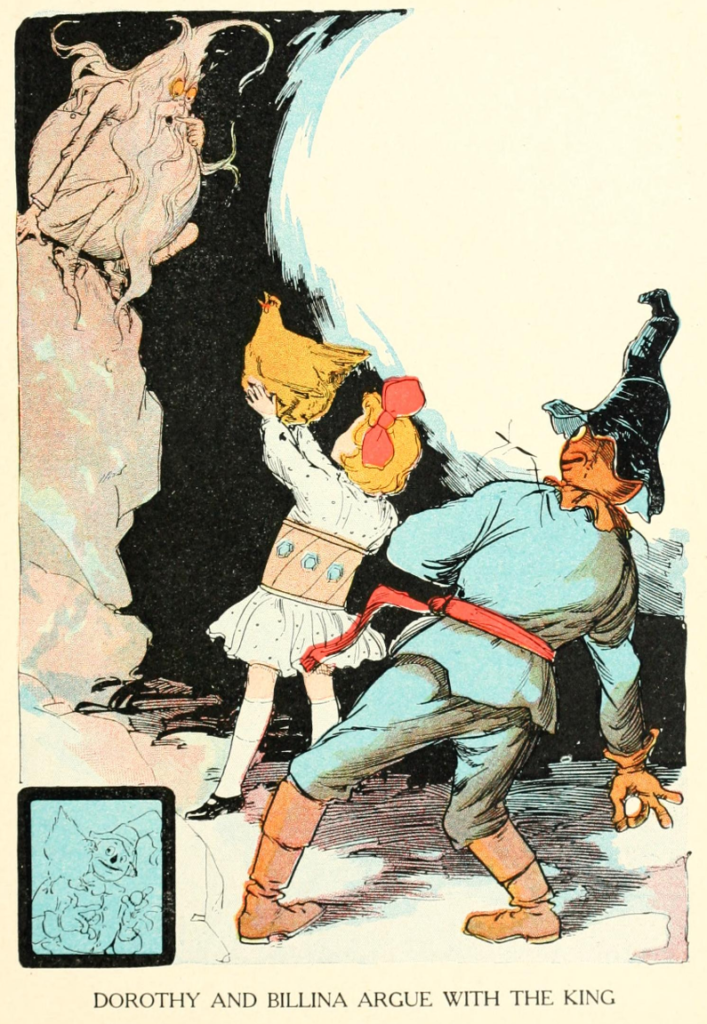

Though incorrectly claiming that only Glinda remains on her throne and independent of Dorothy, forgetting about the Good Witch of the North who rules Gillikan Country, Bell audaciously compares the little girl to Alexander, Genghis Khan, and Napoleon. In subsequent books, Dorothy and her friends are involved in removing Langwidere from power in Ev, defeating the Nome King, overthrowing the Prince of the Mangaboos, killing the ruler of the Gargoyles, and killing or at least severely harming the Queen of the Scoodlers. Dorothy herself then becomes official royalty of Oz. She later overcomes, though does not dethrone, the second Nome King (Kaliko) in Rinkitink in Oz.

The discussion of the Land of Oz has so far overlooked a major feature of Ozma’s Oz: it is not, in fact, synonymous with the whole of Oz. Even in The Emerald City, when the series tips into utopian fiction, some Ozites have nothing to do with Ozma. Baum acknowledges that the Hammer-Heads and Fighting Trees of Quadling Country remain hostile and independent (32), and Dorothy later stumbles upon the town of Utensia, whose kitchenware people have never heard of Ozma (167). The subsequent novels introduce increasingly large and populous swaths of Oz unaware of or else rejecting Ozma, including the countries of the Hoppers and Horners, Jinxland, and the cities of Thi and Herku.

The supposed utopia only reaches as far as Ozma’s authority: Jinxland is rampant with corruption and violence, while Herku continues to keep slaves even though the city is, according to Ozma, under the Tin Woodman’s control. There are rich and poor in Ozma’s Oz. Consider how, in The Patchwork Girl, Ojo, Unc Nunkie, Pipt, and Margolotte live in poverty near starvation in the wilderness of Munchkin Country. The deprivation of those outside her territory is how Ozma lures in, domesticates, and de-magics colorful eccentrics like these characters, as Ojo observes: “There is plenty for everyone, you know; only, if it isn’t just where you happen to be, you must go where it is” (20). And Ozma, Glinda, and the Wizard do succeed in domesticating these eccentrics in what Baum treats as a happy ending: they brainwash the Glass Cat, straighten out Pipt’s crooked body, and destroy Pipt’s magic books and equipment.

The pattern of conquest and suppression walks hand-in-hand with Ozma’s purportedly nonviolent form of civilizing. It literally walks hand-in-hand with Ozma, as “it” is, as often as not, Dorothy. Bell observes, “Dorothy is not merely an explorer of Oz. She’s a conqueror” (14). The notion of exploration of unfamiliar countries has been bound up with narratives surrounding European imperialism from at least the fifteenth century onward—consider popular notions of Christopher Columbus as an “explorer” that elide his role as a governor and slaver cruel enough to provoke backlash even among other colonialists.