Furthermore, the civilized Oz is by no means opposed to killing people, as seen in the Shaggy Man’s eagerness to destroy Vic. Up until she decides her personal extreme pacifism is more valuable than the lives of her “more than half a million” subjects, Ozma herself supports the death penalty with such zeal she repeatedly leaves Dorothy crying.

“I will summon the court to appear in the Throne Room at three o’clock,” replied Ozma. “I myself will be the judge, and the kitten shall have a fair trial.”

“What will happen if she is guilty?” asked Dorothy.

“She must die,” answered the Princess.

“Nine times?” enquired the Scarecrow.

“As many times as is necessary,” was the reply. (Dorothy and the Wizard 235)

The Tin Woodman later confirms to Dorothy that the civilized Oz retains the death penalty, saying, “if one is bad, he may be condemned and killed by the good citizens” (Road 172). At no point do the characters show any indication of reflection on past actions but simply pretend nothing has ever changed.

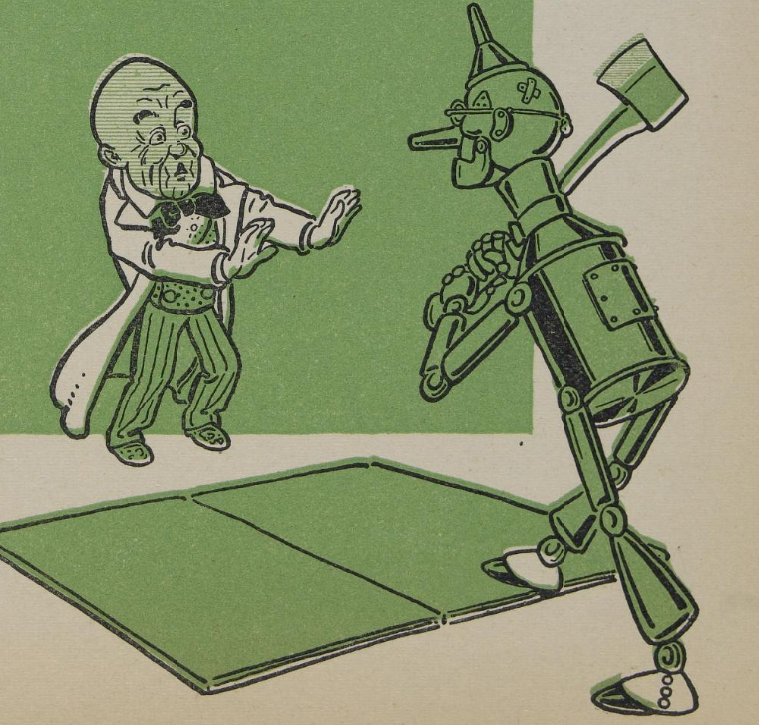

The most striking historical revisionism occurs in relation to the Wizard himself. In the ironically titled The Wonderful Wizard, the Wizard is an ambiguous figure. He is a deceiver who deliberately sends Dorothy and her friends to die in Winkie Country. The Wizard is so astonished when they instead return alive that he spends several days unsure of how to respond, taking action only when the Tin Woodman, still in civilizing mode and not in pacifist mode, threatens him with an ax (183).

But the narrative is broadly sympathetic to the Wizard. He resolves the main characters’ predicaments through further showman trickery but only after the heroes demand what they are owed. And he is also a wise man who correctly recognizes the Scarecrow, Tin Woodman, and Cowardly Lion already possess the attributes they seek, nearly spelling out the central theme with narrative authority. “You have plenty of courage, I am sure,” the Wizard tells the Lion, for example. “All you need is confidence in yourself. There is no living thing that is not afraid when it faces danger. The true courage is in facing danger when you are afraid, and that kind of courage you have in plenty” (189–190). The question of whether the Wizard is a “good man” is raised by Dorothy early on (27), and although she concludes that he is (221), seemingly not realizing he attempted to kill her, Baum is more ambiguous. The Marvelous Land elaborates on the Wizard’s rise to power, revealing a more malicious, conniving character who collaborated with Mombi to overthrow the rightful ruler, Pastoria, and enchant Ozma to be her slave (269–270).

Although I have already described the Wizard’s many morally questionable acts in Dorothy and the Wizard, in that book, Baum, who is fine excusing genocide, feels the need to deny the backstory to protect the Wizard and avoid conflict with Ozma. The author erases Pastoria, never again acknowledging his existence. Instead of collaborating with the Wizard, Mombi has instead acted entirely independently of him (193–195). The Wizard is not made to compensate those he harmed but is allowed to receive adoration while the characters and author gleefully conspire to hide moral complexity and historical tensions from the reader. Even trying to kill Dorothy is treated as an embarrassment more than a crime. When Dorothy mentions it to him in The Emerald City, this is the entire response:

The Wizard sighed and looked a little ashamed.

“When we try to deceive people we always make mistakes,” he said. (244)

And he becomes Glinda’s fawning and unaccountable enforcer, dealing out magical justice for Ozma’s surveillance state dictatorship.