Rahn does not mention that, reinforcing her interpretation, the Nomes even routinely go on strike when their king’s cruelties become unbearable (Tik-Tok 150), suggestive of the union actions that secured workers’ rights in Baum’s day. In Rinkitink in Oz, Kaliko, now the new Nome King, is less personally nasty than his predecessor. Yet he continues the cruel system, alliance with slaving tyrants (Cor and Gos), and imperial attitude and does so on explicitly economic grounds: “[A]s a matter of business policy we powerful Kings must stand together and trample the weaker ones under our feet” (232, emphasis mine). This shows that, as with capitalism, the issue is not the Nome King’s personal character but the nature of his political and economic power itself.

In the Under World, as Rahn also notes, the Nome King marshals his Nomes to manufacture precious metals and gems not to share but for him and him alone to enjoy. Rahn adds that the Metal Monarch’s false kindness mirrors “the presentable face” industrial capitalists such as Andrew Carnegie put on exploitation using their philanthropy (29). In Ozma of Oz, Ozma indicates the dazzling material wealth shared among all the Ozites is a small fraction of what the Nome King keeps in the Under World. “[T]he kingdom of the Nomes is wonderfully rich, and all we have of precious stones and silver and gold is what we take from the earth and rocks where the Nome King has hidden them” (131).

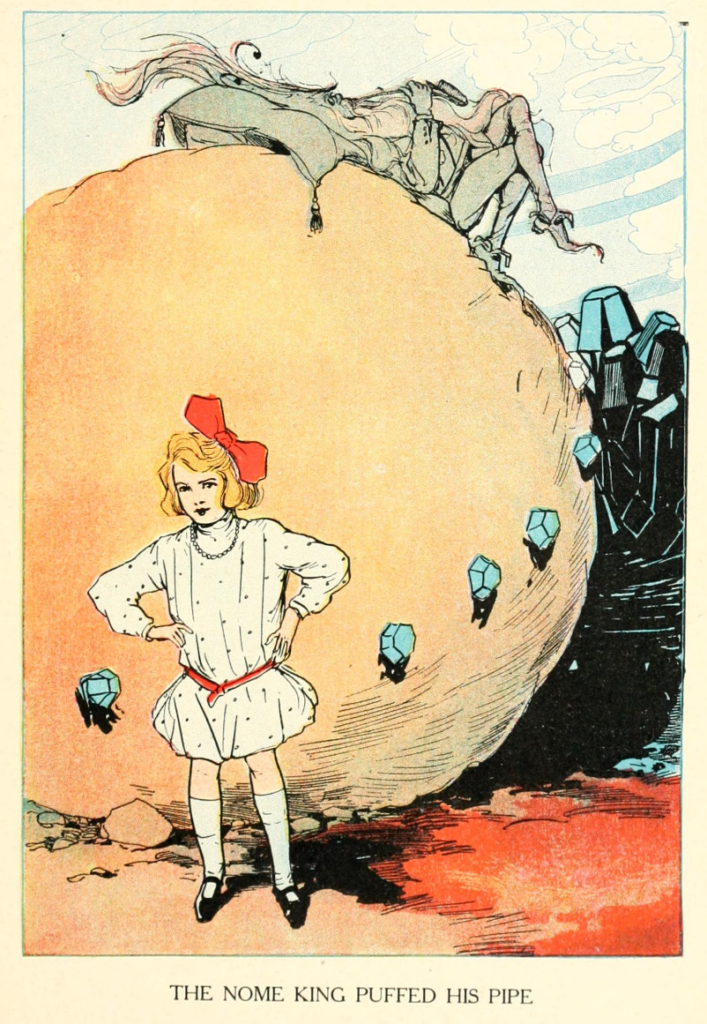

Despite possessing an enormous amount of useless material goods, the Nome King nurtures an insatiable greed like the capitalist oligarch obsessed with growth: “instead of being content with the riches he still possessed he was unhappy because he did not own all the gold and jewels in the world” (Tik-Tok 93). Rahn takes this line to indicate a desire to establish a business monopoly on gold and jewels. In this context, Ozites taking some of the Nome King’s wealth may correspond to socialist expropriation or, in a more liberal reading, taxation of the upper class.

The Under World also stands in opposition to the power of women manifest in Oz. Baum never identifies Nome women, nor does Neill ever distinguish them in his illustrations. In Ozma of Oz, the Nome King takes the Queen of Ev, a powerful woman, as a slave to transform into an inanimate object. In Tik-Tok of Oz, he offers to spare Polychrome only because of her beauty, patronizing to her due to her girlhood: “You shall be my daughter or my wife or my aunt or grandmother—whichever you like—only stay here to brighten my gloomy kingdom and make me happy” (186).

Similarly, the Nome King wants Dorothy and Ozma to be reduced from esteemed and capable girls into his slaves and also transformed “into china and ornaments to stand on [his] mantle” (Emerald City 146). Not only adding to his excessive material wealth, the two girls will “look very pretty,” be seen and not heard and literally objectified, valued only for their appearances. In the same passage, the Nome King gives a rare acknowledgment of women, mentioning “the maids.” This one reference to women in the Under World has them, then, subservient to their industrial potentate, whose goal in all of his appearances (Ozma of Oz, The Emerald City of Oz, Tik-Tok of Oz, and The Magic of Oz) is to usurp women’s power.

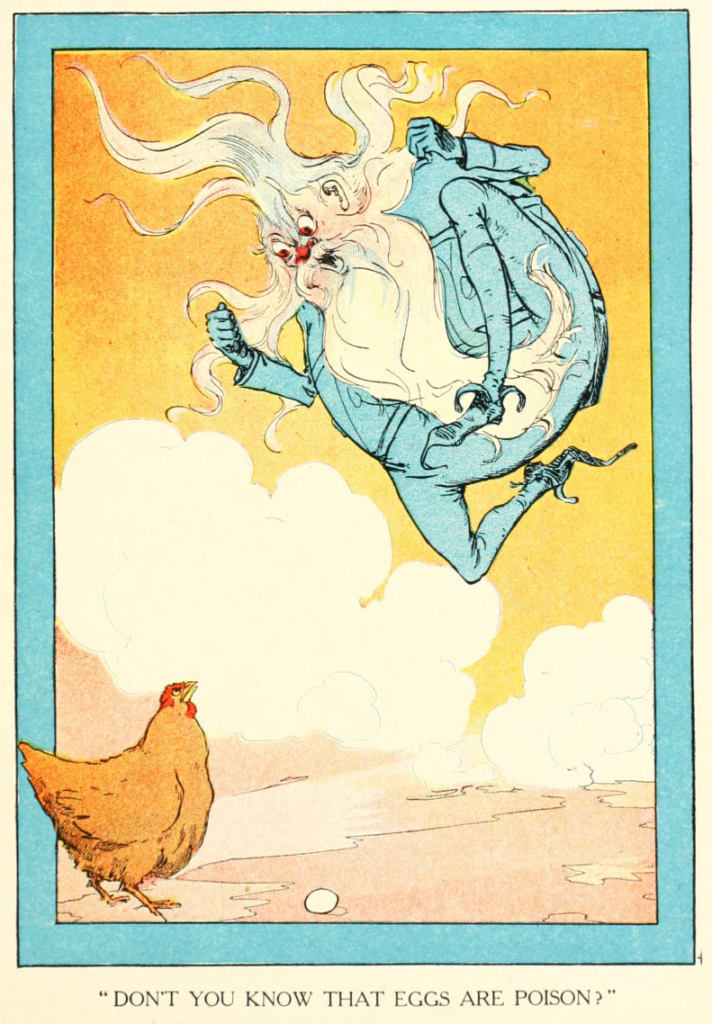

Baum depicts the hairy, fearsome, muscular Nomes as weak against eggs, which throw all Nomes into hysterical fear. She quotes Gage describing eggs as an ancient symbol of female power in Woman, Church and State, a possibly bioessentialist idea by the standards of the 2020s: “The circle, like the mundane egg, which is but an elongated circle, contains everything in itself and is the true microcosm. It is eternity, it is feminine, the creative force, representing spirit” (12). The militaristic, materialistic “rugged men” of the Nome Kingdom dread eggs because they dread the female power of Oz and its corresponding peace and equity. Note also that the eggs in question emerge from the cloaca specifically of Billina, a wily hen who asserts her power over men (though she initially insists her name is the masculine “Bill”). She bloodies herself in triumphant battle fighting off “a speckled villain of a rooster” for his haughtiness (Ozma of Oz 123–124) and refers to the few male offspring she has as “horrid roosters,” in contrast to the “very respectable hens” (Emerald City 71).

If eggs embody women’s power, and the Nome King embodies the violence of patriarchy and capital accumulation, then it is a radical, egalitarian feminism that overthrows this system because Roquat ultimately loses his power not even to Glinda’s Water of Oblivion but to enchanted eggs: “And there were the eggs, forever barring him from the Kingdom which he had ruled so long with absolute sway! He threw rocks at them, but could not hit a single egg” (Tik-Tok 200).