Published 20 May 2021

For privacy reasons, I will not use anyone’s real name in this story. Let’s call the teacher Mr. Elles.

Tall, broad-chested, his head as rectangular as his torso, Mr. Elles was a big guy, at least to my eighth-grade self. He had a goatee and mustache, like Gordon Freeman, and wore black-rimmed glasses, like Gordon Freeman, but with greasy black hair instead of brown, styled like Gordon Freeman’s. To complete this portrait, in terms of demographics, he was a married white man living in an affluent suburb during the Obama years.

This teacher’s most distinctive quirk was the Ellestick, a sawed-off wooden beam painted black with a few holographic stickers smacked on. Most frequently, Mr. Elles used the Ellestick to point at words or images in his PowerPoint slides or else as a prop for his lectures, standing in for any object imaginable. I picture him smacking his open palm with the Ellestick like a riding crop, though I do not know whether that happened or my mind has extrapolated. The class before ours had written up a list of all the uses to which Mr. Elles had put the Ellestick over the last year. It seems at some point he stirred a cauldron with it. The list also reported that there was a boy who repeatedly fell asleep in class, and Mr. Elles would whack his desk with the Ellestick to perk him right up. I do not doubt for a moment that, if schools still allowed corporeal punishment, Mr. Elles would have beat students with the Ellestick. He openly told us he believed beating children was the best method of discouraging bad behavior and that he administered this treatment to his own kids.

Mr. Elles reveled in frightening middle schoolers or at least pretended to. During tests, he would don a pair of mirrored sunglasses like JC Denton. Mr. Elles claimed that, years before, he had, without thinking about it, forgotten to take off his sunglasses when he began a lesson. Noticing that the class seemed frightened, he asked why, and they pleaded with him to take the sunglasses off. Appreciating the intimidation factor, Mr. Elles would wear them during tests so that we could never be certain where he was looking. This would theoretically discourage cheating. Another, more ordinary form of intimidation was the perpetual threat of pop quizzes, which Mr. Elles delivered more frequently than any other teacher I ever had. On his desk, in the back of the room, alongside a nameplate and pens and paperwork and perpetual tests and quizzes to grade, sat a jar full of some kind of purplish powder. Max Martinez asked him once what that stuff was. Mr. Elles answered, “The ashes of rowdy kids.”

That was the age when I first began realizing my fasciation with history. Adults already told me that I had an incredible ability to not only remember historical information but to convey it in an engaging way. And so history teachers appealed to me, especially since I found Mr. Elles less intimidating than the previous one, a grouchy woman who only stopped screaming when her voice inevitably got hoarse. Incidentally, the SAT-obsessed history teacher who taught us the year before the shouty teacher later, I heard, smashed a SMART Board with a stick of her own. In comparison, Mr. Elles spoke softly. Teddy Roosevelt would approve. Mr. Elles was always nice to me. I think I was his favorite student. He called me “Big William” since I used to be tall, and he occasionally chatted with me after class. There were other students he gave nicknames, such as one boy named Melt whom Mr. Elles dubbed “Global Warming.” My resultant fondness for Mr. Elles might be why, at the time, I interpreted his threatening behavior as only jokes.

This being an American public school, where children daily pledge serf-like Christian fealty to the cult of the Stars and Stripes, of course Mr. Elles instructed us in American history. I believe this was the second propagandistic rehash of the American Revolution we went through, after two years surveying ancient Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia, and China.

Mr. Elles began the unit with a projector slide about “the Man” and “THEE man.” Pointing the Ellestick at “the Man,” Mr. Elles explained that this was the Man you have to stick it to. We were not confuse this oppressor with THEE man, Mr. Elles’s tutelary deity, George Washington. THEE man stuck it to the man. Some Americans worship Washington on the same level as, if not Jesus, then at least one of the apostles. But Mr. Elles never missed a chance to gush over the adventures of THEE man, this general full of a selfless devotion to democracy and American independence, his love of dogs, his attempts to whip up a bunch of drunken militia bumpkins into soldiers, anecdotes about action film-esque badassery. It may be worth mentioning that Mr. Elles showed us both Saving Private Ryan and The Patriot starring Mel Gibson. Propaganda is to many Americans what water is to fish. Only Andrew Jackson inspired almost as much enthusiasm in Mr. Elles, though there the blatant genocide, contempt for the Constitution, and baseline incompetence left him enthused more about the funny anecdotes, like the time Jackson let a drunken mob ransack the White House, than full of moral admiration. Still, Mr. Elles loved that self-admitted jackass.

Listening to history as Mr. Elles told it finally persuaded me that the British really were the bad guys in the American Revolution. The British certainly were bad guys. It’s just that the other side was also a white supremacist slave empire driven by greed and intolerance. Though Mr. Elles romanticized Washington as a brave patriot who, at the end of the day, wanted most of all to be a humble farmer, he did not totally gloss over that being a humble farmer meant having the human families Washington owned as chattel do the work for him. Mr. Elles tried to explain that, due to the economic realities of the day, Washington could not easily free these people he legally owned and that Washington was not a particularly cruel master, not the sort who would rape them or rip their teeth out, and that, anyway, Washington willed the Black folks at Mount Vernon freed when he died.

The apologetics won me over. Mr. Elles left me in almost as much awe of Washington as he was. For a few years after that class, every new detail I learned about THEE man seemed to improve his standing in my eyes. Washington became a personal hero. So successful was Mr. Elles at establishing this cult of personality that I did not notice the absurdity when he showed us a straight-up Renaissance-style painting of George Washington as a demigod in Heaven replacing St. Peter to welcome the freshly assassinated Abraham Lincoln. Most of my peers were not, I think, sucked in half as much because few of them took history seriously. In retrospect, in the context of the narratives they were fed at the time, they were wiser than I.

While Mr. Elles might have wanted to gloss over American racism, I noticed that he could not escape it. He definitely picked on the kids of color in the class. These three individuals, together, constituted more than half the non-white students in the entire grade. One of them was Max Martinez. He was a crude wannabe tough guy who participated in his own racist harassment of Asian students but was no more or less crude, wannabe, and racist than (many of) the white boys who flippantly mocked Jews and gay people (including after a visit by Holocaust survivors, one of whom promised us it would happen again unless we absolutely opposed the tiniest forms of bigotry even in our speech). The other two non-white students were Black girls, best friends as far as I knew. Hanifa tended to be bolder and more aggressive with the righteous indignation of a socially conscious person. The other, Katie, was something of a ditz but friendly and not at all assertive. Incidentally, at the time, I had a bit of a crush on Katie. Both girls were fashion pioneers. A certain outfit in Hanifa’s rotation complimented its bright colors with two Tootsie Pops stuck through her bun in place of hairpins. Once, attempting small talk, I asked about Katie’s new glasses. “These are fake,” Katie said, removing them to demonstrate there were no lenses.

Max, Hanifa, and Katie must have noticed that Mr. Elles picked on them. They must have seen through his narratives too. I do not believe that I ever saw Mr. Elles step into genuine harassment, especially given his uniquely baseline authoritarian inclinations. But he teased and called on these three more than anyone else. I never heard anyone point it out. The next year, Hanifa and Katie disappeared to, I later learned, a technical school.

Mr. Elles, in short, was conservative. That is to say, if push came to shove, he probably preferred capitalism to democracy. Of course, he also loved him the Second Amendment. After an active shooter drill, that most dystopian of phrases, Mr. Elles told us that teachers should be allowed to carry a gun in the classroom. “Parents already trust us with their kids for most of the day most days of the week,” to attempt to quote him. At the time, Mr. Elles persuaded me. I always trusted adults, especially kooky yet authoritative men. The thought that living in a state of constant militarism might be unhealthy for developing minds did not cross my mind. Though Mr. Elles could not have a gun in the classroom, he did keep a baseball bat on top of the cabinets. The Ellestick, while more distinctive, would not have been half as effective at cracking a skull. Mr. Elles could only have been a more perfect portrait of these quirky, patriotic but not personally vicious suburbanites who daydream about saving the day with righteous violence if he had been one of those mythic small business owners that pundits use to bludgeon the teeth out of whatever already limp regulation the lobbyists are opposing that month.

Only gradually did the scales slide from my eyes. I realized, wait, Washington led a “revolution” largely to maintain the wealth of his white supremacist planter class and continue the genocidal conquest of the Native American nations. These actual slave owners had the temerity to compare arguably unreasonable taxes to bondage? When the issue of dispute between the sides of the war is a tax related to the defense of imperial borders and most of the “heroes” are, again, white supremacist slave owners, it is hard to feel too invested in which crew of rapists and thieves comes out on top. Looking back, I understand why my peers considered Mr. Elles pathetic and bizarre. A few years later, one boy I knew happened to describe Mr. Elles as an old man who, out of utter impotence, bullied middle schoolers for a power high.

In high school, after that history class had become an ambiguous memory, I met Mr. Elle’s daughter Sarah. She bleached her hair blonde to really highlight the brunette roots. Her heavy makeup was not the sort meant to draw attention to itself like, say, green lipstick, but to make her face extra pale and her eyelashes extra dark. Sarah had heard about me from her father (he really liked me!) and so sought me out. Though desperately lonely, I never considered Sarah Elles a serious candidate for friend or anything else, this girl too many years younger than me and, in personality, for lack of a better phrase, not weird enough. The girls I (rarely, barely) hung out with were nerds who laughed about Slenderman and played Ib. Sarah was more of a “popular female clique”-type like you see in cartoons, although there was no particularly popular clique one way or another so far as I knew. The last time we spoke, Sarah asked me, apropos of nothing, “Do you think I’ll ever find a perfect someone who’s kind and smart and really hot and loves me?” Confused, I told her something to the effect that nobody is perfect. That seemed to make her sad, so I added, sincerely, that I was sure she would get together with somebody fine. I was a smooth operator. Sarah, I guess, was one of those kids whom Mr. Elles beat.

What might be surprising about Mr. Elles is that he was the first person who introduced social issues to my psychic landscape. He once quoted somebody claiming that gay people were no longer discriminated against. Mr. Elles said nothing could be further from the truth. “That’s like saying Black people have overcome racism,” Mr. Elles said. “And think about it,” he went on, still and blocky, fidgeting with the Ellestick. “If you’re straight, did you decide to be straight? Or did you just feel attracted to whoever you felt attracted to? God made gay people that way. So I’m not going to judge them.”

Do not overestimate Mr. Elle’s progressivism. He went on to say that he believed homosexuality was a sin, though he also believed in the Golden Rule and forgiveness—even, he said, of John Wayne Gacy if that murderer had sincerely repented. But those comments, in particular the persistence of racism, had, for the first time ever, exposed sheltered little me to contemporary social justice issues. On another occasion, Mr. Elles commented that he would never blame an Indian for bearing white people a grudge. I wish to be clear about this: Mr. Elles made some effort to point out the atrocities and hypocrisies of the historical figures he clearly admired. Mr. Elles even told us about the Gnadenhutten massacre. None of his ideas were particularly insightful, but they, planted in my mind at a formative age, are the germ of my social consciousness. Yet Mr. Elles still adored Washington and the heinous Jackson. What admiring someone whom he concedes to have committed genocide says about a man, I leave for others to decide. But there are millions of Mr. Elleses who bear the same sort of admiration. How many of them think even to feign self-reflection?

I used to wonder what happened to the Mr. Elleses of the world. As a kid, I noticed these shortsighted, awkward conservative old men dominating most of the community. Though vaguely uneasy about them, I also knew they were reasonable. The Mr. Elles types would talk to me cordially, assuming that I, too, would someday join their ranks, never discussing my emotions, interested in guns to defend myself from the nebulous hordes of barbarians who, on some level, we all knew we had wronged, married with kids in my own house with my own garden working some respectable job for respectable wages. One might call them Eisenhower Republicans. While that term is my language, not theirs, I would wager that none of these men, or their womenfolk either, knew what Eisenhower got up to in Iran and Guatemala. But they did not unquestioningly idolize the past. They believed socialists were wrong, but, not latching onto the ideas of the original Nazis, would not have slandered them as engaging in a “cultural Marxist” plot. If Bonanza was on, they would laugh at how campy and unrealistic these Westerns were. Like Mr. Elles, they admitted the evils of slavery and genocide. But all of them would have been outraged at the suggestion we redress any of those historic wrongs. They all supported the Iraq War and wondered what everyone had against Bush. Most of them, proudly unintellectual or else proudly intellectual exclusively about pseudoscience and false historical revisionism, believed in assorted conspiracy theories, at the very least related to Area 51 or JFK. Almost all watched Fox News, to which so many people have lost their families. They sometimes remarked, only half-jokingly, that we kids were “brainwashed” into thinking climate change existed. I knew none of them to use slurs themselves, but they would reject criticism of cruel humor mocking minorities.

I have not seen Mr. Elles in years. If he still works at that school, I could always visit, but I prefer to keep him a memory. I do not want to know how he ended up in the age of Trump. Did he forget his slightly anti-racist and anti-homophobic positions and Golden Rule theology to embrace the openly white supremacist sexual predator? Did slight pushbacks against racism cause him, too, to give in to the worst aspects of his disposition? Is he among the elders who lost his mind to Trumpism or to conspiracy theories like the thousands fallen to sinister nonsense like QAnon? Perhaps Mr. Elles has become a better person. Perhaps Trump was too far for Mr. Elles. But Trump’s favorite president is also the incompetent, genocidal white supremacist fake populist Andrew Jackson. I do not know if Mr. Elles the person went down any of these routes to fascism. But Mr. Elles the concept did. There are no more wholesome, bumbling conservative old men. I realize, now, there never were. I have seen the Mr. Elleses become bolder in their snickering at women, embrace of racism, remarks that dissenters should be summarily shot. I still recall seeing a certain pair of Mr. Elleses furious when they realized some guy they had known in college had since been called racist for supporting voter suppression. “Imagine—him! Racist!” As though the mere notion that somebody they had not seen in years might be racist was so absurd it should be dismissed out of hand. They responded this way because they, correctly, sensed their own unchallenged racism. They could, correctly, imagine themselves as abusers before they could ever imagine themselves as victims.

It is no wonder that so many Americans swung toward fascism, and not only because of voter disenfranchisement in the opposite direction the Republican propaganda now lies about. Fascism, starting from the OG fascists in Italy, is always about the dominant class of an imperial state, feeling threatened by the barest possible concessions the left has eked out, importing the terror the empire used abroad back to the metropole on the wings of a mythologized glorious past based on their vague nostalgia for childhood and intense and perhaps unconscious fear of a reckoning for their country’s injustice. In the US, after the systematic destruction of a legitimate mass left-wing consciousness during the Cold War, with no narrative floating around that actually explains what has gone wrong, it is no wonder millions have latched onto baseless conspiracy theories and that this nonsense skews increasingly toward fascism. It is even less surprising given the sorry state of public education that has resulted from the systemic neoliberal looting of every aspect of human existence. Further, when the returning left-wing narrative points to the Mr. Elleses’ free market articles of faith as the cause of what went wrong, rather than accept their error, they latch onto whatever narratives allow them to dodge the inconvenience and pain and self-doubt of what they have done to their children so that they can preserve the everyday comfort of their dwindling years.

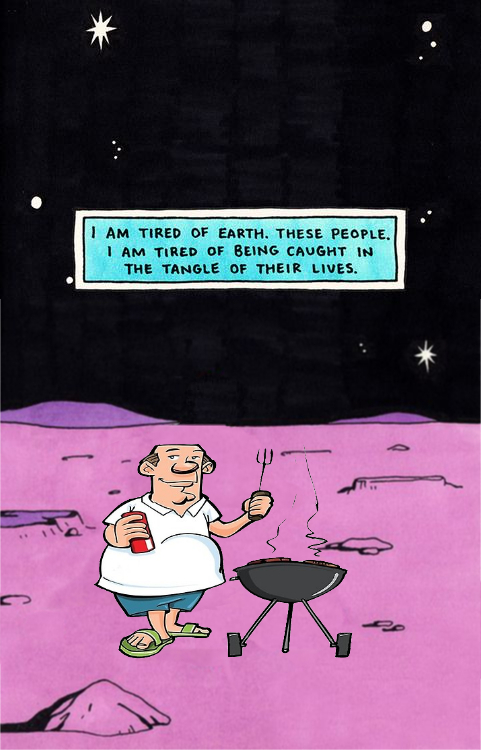

If fascists torture you, it is hard to be too angry. After all, they are fascists. That is what they do. It would be like being angry at piranhas for tearing the flesh from your bones. Upsetting, yes, but what else did you expect? I am not angry at the piranhas. That is what horrifies me about fascism, what enrages me: it is that, almost to a man, all those reasonable if kooky Mr. Elleses of my childhood turned to fascism, cluelessly, often gladly. It is that they would probably see me put to death for living peacefully so long as their lives would stay convenient. It is the retrospective realization, obvious to all the victims of American empire, that the Mr. Elleses and me too, since my earliest childhood, live on a mountain of corpses, of all those tens of millions dead in the slave trade, in the genocide of Haiti and the conquest of Mexico and the Pequot War and the Sand Creek massacre and the hundreds of other crimes of the plundering, hypocritical settler colonial capitalist system that will soon have killed the earth. It is the ignorant complacency of millions like me that led to the fascism that emerged in the Trump years, which will soon return, and much worse, because nobody held Trump accountable. I will probably regret not fleeing the US while I could (or couldn’t, since I lack friends or money). I am angry at the many Mr. Elleses in my life because they, seemingly kind, would, if events came to it, push me into the piranha tank.

What horrifies me about the little fascists is, paradoxically, that a Mr. Elles is not pure evil. If someone could be ontologically evil, that would, in a way, be comforting. This facile explanation for how people one knows could be indifferent to or compliant with cruelty is the same that leads the fascist to conceptualize their (imaginary) enemies as pure evil. After a certain YouTuber was outed as a groomer (pity that doesn’t narrow it down), some former fans claimed that all of his past friendly behavior, all the videos opening up about his trauma and personal life, had been a façade erected to lure in helpless teenagers. Maybe. But I doubt it. The uncomfortable truth is that certain people who can be sincerely thoughtful and kind can, in other circumstances, terribly hurt you without a drop of remorse. They have their own narratives to keep their sleep peaceful. After all, George Washington could go on hunts for enslaved people, while claiming he highly valued liberty, and George, I assume we all agree, is a hero, so how bad can I be if I harm you now?

Mr. Elles truly did win me over back then. I am not bitter. A previous Mr. Elles must have won him over too. There, but for the grace of God, go I. Sometimes I recall the H. P. Lovecraft story “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” in which the narrator discovers nightmarish human-fish-hybrid monsters who rule the city Innsmouth because their ancestors achieved economic prosperity at the cost of their literal humanity. The narrator escapes them. Later, however, he learns that his family comes from Innsmouth. He, too, is becoming a fish-monster—and, worse, he likes it. I have long been terrified that I too was cursed from birth to become another Mr. Elles, no matter what I do, no matter how far I might run. This is because the only way to stop that process is to fight it, and I am no fighter. The fascist bigot H. P. Lovecraft, of course, did not care about generational wealth. He meant the story to be about miscegenation.

The last time I saw Mr. Elles was in either my sophomore or senior year of high school, when I happened to be visiting the middle school for some reason. Already there, I decided to stop by and say hello. Mr. Elles, hunched over his laptop, sat at a desk, not his big desk in the back of the room but one of the child-sized desks the eighth graders used. The Ellestick leaned against the corner by the pencil sharpener. The tile, the florescent lights, the American flag on the wall, all were the same as when I had sat there adoring George Washington. It was like stepping into a memory. Looking up, Mr. Elles said, “Hey, Big William!” Perhaps I had grown taller, or it was that I stood while he sat, but Mr. Elles alone looked different. He was so small. Drenched in sweat, he smiled, but not wholly, his expression somehow strange. Having made some perfunctory comments, I left him there, grading assignments.