While the process entails battling the Matsumae oppressors, Worso specifically fights to stop “[t]he disturbance in the order of all things in nature” and “[t]he disturbances we now face in the order of all creation,” as well as “to maintain the ways handed down to us by our ancestors.” It is on this basis that he rejects wealth accumulation and claims to uphold pluralistic values, while Antonioni seeks material wealth and openly chooses genocide over coexistence.

Worso fights for these seemingly laudable perspectives. But what this Kamui is fighting against as unnatural and nontraditional is just as important and reveals a clear conservative bent. Not only do the foreign oni’s lower ranks move and behave like animals, but the Europeans are also “demons” and “degenerate aristocrats,” always described and portrayed with dehumanizing language, who come to Japan specifically to prey on local women, kidnapping them to rape in their dungeons and, apparently, literally eat. Meanwhile, they use their financial power to secretly wrest control of the government from the Japanese Matsumae.

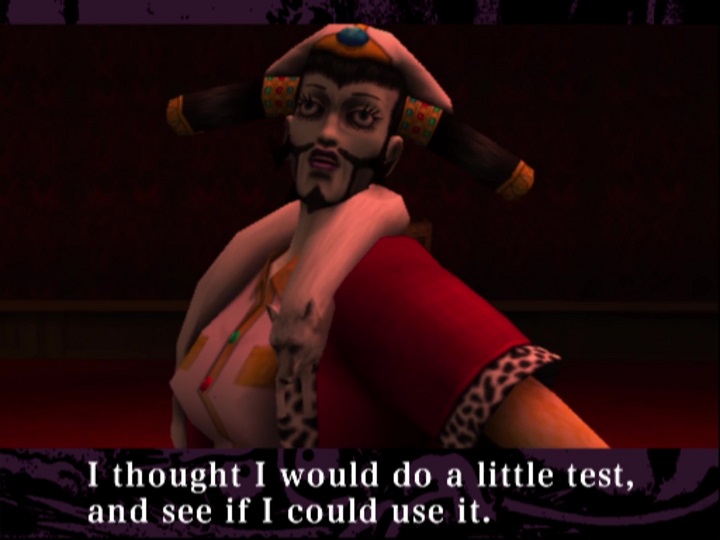

This “degeneracy” is specifically linked to the Europeans’ gender and sexuality. The first oni leader the player fights, Bulykin, has a full beard but also makeup, jewelry, and prominent breasts. They preside over a sex slave dungeon and gloat about how people like them possess “noble souls” the conservative Jin will never comprehend. The story mocks the notion of Bulykin’s queer expression.

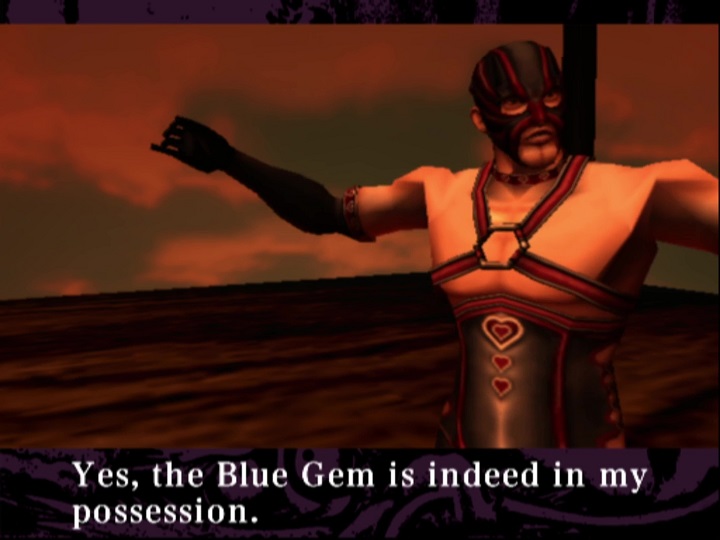

Antonioni is gay-coded, a campy, buff man wearing leather bondage gear decorated with hearts. The camera focuses on his crotch and buttocks in an introductory cutscene where he threatens to rape Fuu and implies he is pedophile.

One or two of these unfortunate tropes is not uncommon in pop culture, but cumulatively they paint a concerning picture. The association of queerness, camp, and foreignness with rape, “degeneracy,” demons, cannibalism, and animalistic behavior is such an ugly grab-bag of anti-queer ideas and xenophobia that it is almost parodic. I had intended to address this in the previous chapter of this essay when questioning what values Kamui is associated with but could not find a way to fit it in.

Certainly, the Europeans’ exaggerated accents (in the Japanese-language version), mishmash of names (Russian and Italian), and goofy dialogue are comedic. Antonioni is as much a hammy pro-wrestling heel as he is a sex freak. But this hardly undercuts the conservative narratives about queer identities as degenerate ideology the “West” forces on other countries and immigrants being shifty barbarians out to rape local women and subvert sovereignty. The bigotry of the material guts any legitimate critique of European colonialism. It also suggests that when Worso-Kamui insists on maintaining the ways of his ancestors and stopping the disturbances in the order of creation, he may be fighting a fascistic concept of “degeneracy.”