Chapter 3: Declaration of the Rights of Kamui

Kamui’s creative destruction

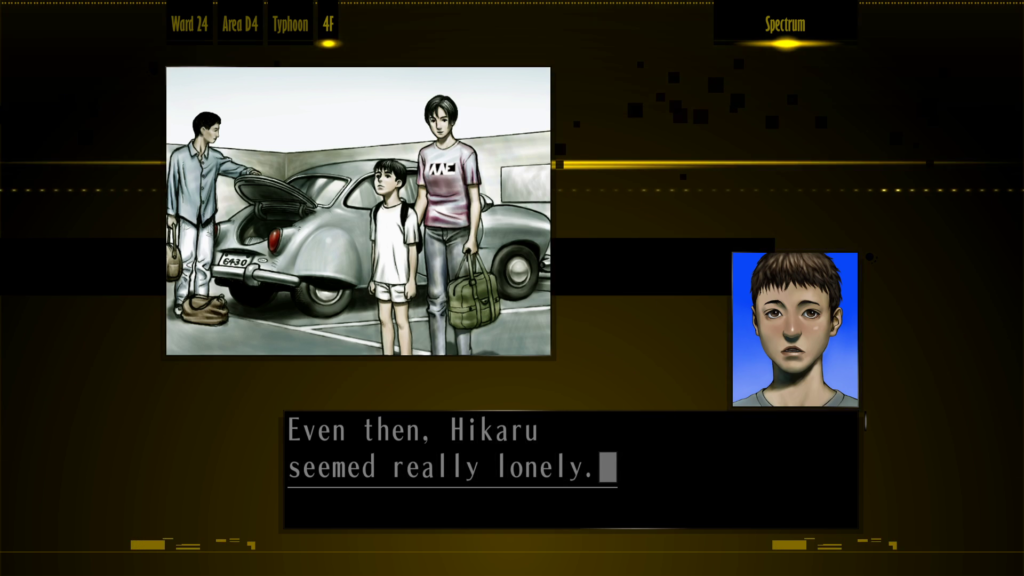

“Kusabi is partially correct about crime being manufactured and having a source,” writes Freeman. “The source is not Kamui, but an impenetrable monolith of oligarchs with Uminosuke at the top that purposefully maintains a cycle of crime, dehumanization and death for their own self-interests” (67). The Shelter Kids Policy represents the social and economic neglect and violence of the rich against the poor, the way that the ruling class creates the social and economic conditions that generate crime. These are the conditions that “Spectrum” and “Hana” depict literally in the story of Hikaru and Koichi.

The Silver Case rejects more essentialist readings, that criminals are just evil monsters as many far-right narratives, or “Lunatics,” suggest. The deprivation and propaganda create and perpetuate the cycle of crime. The light that Kamui chases is one that refuses this cycle that is reincarnated again and again like his transmigrating soul to create a society that instead allows each individual to pursue self-actualization.

Enzawa has rare albeit unreliable insight into Kamui/Ayame. He tells Tokio, “Kamui possesses a terrible creative power. Don’t you think so? With that creative power, he’s able to distort everyday things. Did you know that? Most people known as ‘geniuses’ are the same. The creative power of a genius holds the power to encroach upon reality. And so,— to me, the crimes he commits are a type of creative work. Even his murders.”

The connection seems clear enough. Fujiwara is an artist. But the savior Kamui is a revolutionary, and so is Uehara. Akira and Kusabi do not kill Nezu just as revenge but to demolish the shadows, the old men, so that the young can build “fuckin’ awesome” new millennium, a new society without the oppression of the former police state. Creation, as of Fujiwara’s art, and destruction, as of the savior Kamui’s assassinations, are closely connected. The late anthropologist David Graeber wrote an essay entitled “Super Position” about superheroes. There Graeber reflects on the link between the state and constitutive violence:

“[I]n the modern state, the very status of law is a problem. This is because of a basic logical paradox: no system can generate itself.

“Any power capable of creating such a system of laws cannot itself be bound by them. […] The English, American, and French revolutions changed all that when they created the notion of popular sovereignty—declaring that the power once held by kings is now held by an entity called ‘the people.’

“‘The people,’ however, are bound by the laws. So in what sense can they have created them? They created the laws through those revolutions themselves, but, of course, revolutions are acts of law-breaking. […]

“So, laws emerge from illegal activity. This creates a fundamental incoherence in the very idea of modern government[. …] It’s okay for the police to use violence because they are enforcing the law; the law is legitimate because it’s rooted in the constitution; the constitution is legitimate because it comes from the people; the people created the constitution by acts of illegal violence. The obvious question, then, is: how does one tell the difference between ‘the people’ and a mere rampaging mob? There is no obvious answer.”