Akira/Uehara and Kusabi are policemen, even if they defy and kill other police. Kusabi never explicitly renounces his former life as a cop. Suda writes Akira and Sakura as remaining in the police force even after this organization tries to kill them and their friends and they learn their job is to uphold a hideously cruel and unjust power structure, and Kusabi approves. The official timeline also indicates a series of cases after 2000 that involve Kusabi, apparently as a policeman, though a complete lack of details makes these nothing but lists of names. This seems inexplicable unless one considers a right-wing or even fascist bent to the violence they carry out in “LifeCut” and, in turn, that Tokio executes.

As Graeber observes, the left “has largely moved away from its older celebration of revolutionary violence” such as Fanon’s. Meanwhile, for the right, law is conceptualized as “a means of controlling the very violence it brings into being, and through which it is ultimately enforced. This makes it easier to understand the often otherwise surprising affinity between criminals, criminal gangs, right-wing political movements, and the armed representatives of the state”—such as Akira and Kusabi, and their relationships with Kinjo’s criminal organization, which they make no effort to stop, and with the former criminals in Natsume’s Republic. “For the far right, then, it is in that space where different violent forces operating outside of the legal order interact that new forms of power, and hence order, can emerge.” Graeber understands this as the setting of all superhero stories, and I would add it is also the setting that The Silver Case reaches with “LifeCut” and that the series remains in for killer7 and The 25th Ward, “[a]n inherently fascist space, inhabited only by gangsters, would-be dictators, police, and thugs, with endlessly blurring lines between them.”

***

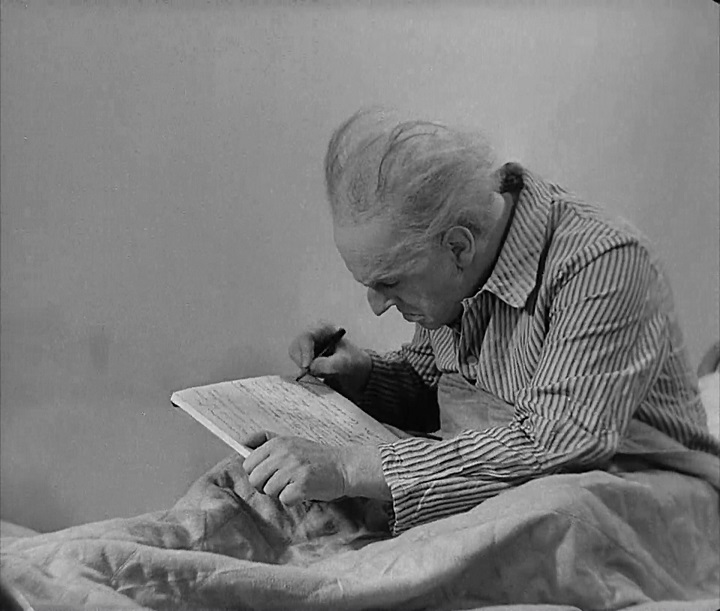

I know of only one artistic precedent for the fourth Kamui, an ideology that physically manifests in criminals, spreads through the dissemination of information, and is also a ghost moving to new bodies to perpetuate itself. I refer to The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, a 1933 thriller. The director, Fritz Lang, claimed in 1943 that the film is “an allegory to show Hitler’s processes of terrorism” (quoted in From Caligari to Hitler by Siegfried Kracauer 248), which matches my own reading. Dr. Mabuse, a psychic criminal mastermind who changes his physical appearance and supernaturally causes those around him to bend to his will, has been thwarted. He ends up confined in a mental hospital, where he begins scrawling out a testament: an extremely complex conspiracy that his followers then broadcast to the public and spread further, gradually creating a vicious “empire of crime” that aims to plunge the world into horror and replace normal society. Eventually, Dr. Mabuse dies, and his ghost transfers into Baum, the most loyal disseminator of his plots, representing the perpetuation of his ideology.

There are several parallels to Kamui: a supernatural master criminal threatens the state, is put in a mental institution, magically causes those around him to become criminals, and continues to literally and metaphorically live by possessing others with “criminality” that Lang might as well have called criminal power. As in The Silver Case, the antidote to the criminal disease that literally lands people in hospitals is not revolutionary organization but the police: the primary hero is Inspector Karl Lohmann, from another film in the series (M, which also features a parallel crime society inventing its own laws).

These narrative tropes about a demonic thought contagion could be used for another purpose, but the similarity suggests the associations that might be inherent to them. The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is a sequel to the 1922 Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, whose portrayal of a financial conspiracy against Germany through media manipulation and the spread of sex and drugs, all masterminded by the hook-nosed Mabuse, reeks of antisemitic tropes, especially given the party that would rise to end the Weimar Republic.

This highlights a point about The Silver Case: the conspiracy cocktail underpinning Kamui/Ayame involves sleeper agents, a lying media, government brainwashing, international secret societies, and powerful elites preying on children, defining narrative features of especially virulent right-wing ideology. Consider the obsession with baroque, grizzly fantasies of child torture and exploitation central to Qanon’s or Alex Jones’s incoherence. Applying a 2023 context to this older media may not be totally justified, but Meru describing the abducted four-year-olds being “cut up and sold to rental shops for rich men to pick up” through a government conspiracy that occurs in a secret underground facility, or the US government engaging in the trafficking of sexually exploited children, seem concerningly close to the tropes of far-right conspiracy religion.

Other aspects of reactionary conspiracy theory culture seep into the later installments of the series I will discuss below. In killer7, the United Nations acts as an oppressive global dictatorship, a hallmark of “new world order” conspiracists who fear “globalists” or the “cabal” or demons, aliens, or Jews conquering Earth. Governments are secretly run by various demonic/divine beings and zombies, familiar tropes in Evangelical and general religiously-inclined apocalyptic conspiracy cults. Note also that an opening episode of The 25th Ward is titled “new world order,” and the narrative overall depicts a technocratic, eugenicist police state like the kind conspiracy cults and scammers fear-monger about (even as they aim to construct one). The presence of these tropes and of “gangsters, would-be dictators, police, and thugs, with endlessly blurring lines between them” at least invites people on the far right to understand the material on their terms.

***