Even Newtype Kamui will not lead a peaceful life. “Black out” depicts him leaving Travis and returning to Ward 26, a new atrocity against the public, only to find an active warzone. More ghouls always appear to continue the “cycle of crime, dehumanization and death” for their profit. The despairing worldview is resonant. Haynes concludes, “a glance around at both liberal and conservative governments […] fills me with nothing but despair. […] [A]s far as I’m concerned at the moment, the future is well and truly cancelled.”

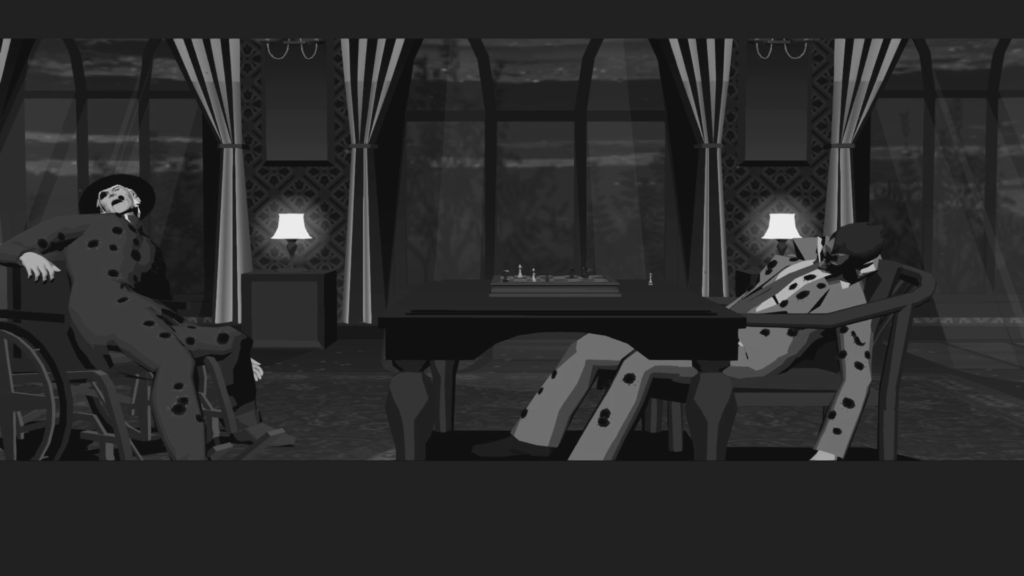

Hence killer7 and The 25th Ward recast Kamui and his “future” accordingly: failure, self-destruction, oppression, escalating violence, futility, erasure of identity. Utopian rhetoric of peace, cooperation, and progress papers over nihilistic false utopias, harsh information control, ubiquitous surveillance states, mass death, and oligarchic gerontocracies. The neoliberal “end of history” is depicted as true but as an unending nightmare and betrayal. As Matsuoka says, hail to the free world.

In 1999, Kusabi is so optimistic about overcoming the old men: “It’ll be a new age soon. Aren’t we lucky? To be born in this age so that we can witness such a wonderful moment.” He accepts that crime, or violence, originates from social conditions and that change is possible. By “Smile,” in real-world 2005 and fictional 2011, Mills, already dead, instead delivers, “The country has been revealed for what it is—a monster. But will anything change? You expect some revolution? Well, a dog can’t do shit.” Then, in “Lion,” Matsuoka reckons that violence cannot be prevented because “terrorism is the law of nature,” and Kun Lan declares, “The world won’t change.” And it does not. Perhaps the most Kamui can hope for is slaughtering Uminosuke and Nezu, or Harman and Kun Lan, in an act of revenge. By the twenty-first century, they are too late to save anyone, but maybe a terrorist can enjoy some personal catharsis before suicide. The past is not dead.

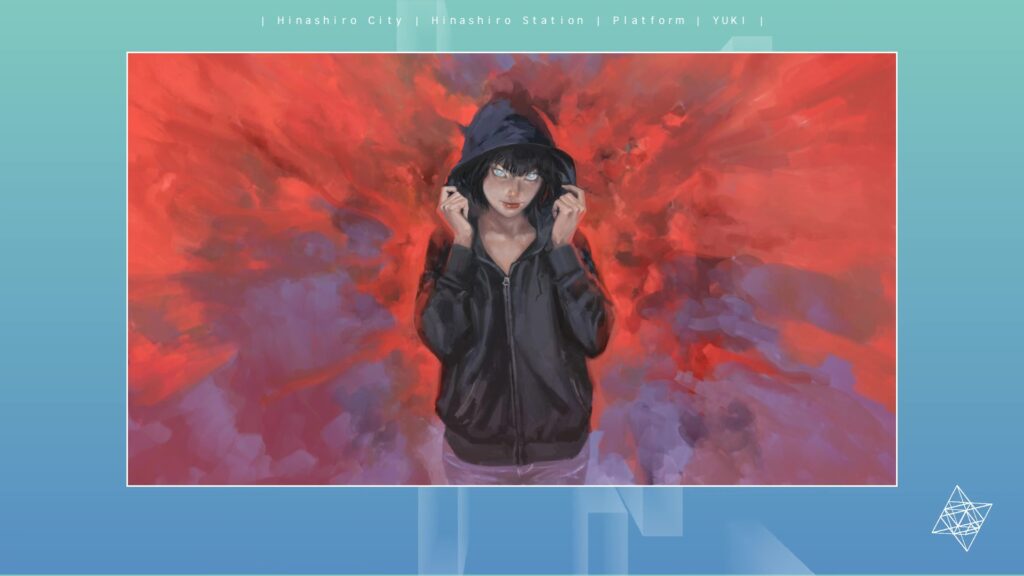

In the original 2005 release, The 25th Ward apparently ends with Tokio shooting himself to join Meru and the others. Suicide is the only possible escape from the cycle of oppression. But by 2017, in “YUKI,” Ooka instead preserves his life so that Tokio can serve as a mentor to the next generation. Yuki, a young girl, embodies this future, the hope of the young denied to people like Sakamoto. When Yuki commits herself to fighting the past, her eyes become silver: she is, at least symbolically, the new savior Kamui/Ayame.